The basis of all printing inks is colour (in which term is included

black) and varnish, the latter serving as the vehicle or carrier of the

former. Lamp-black is made by burning creosote or other oil in a chamber

to which a quantity of air is admitted, insufficient for complete

combustion. The result is the production of soot, just as an oil lamp

produces smoke or soot when the supply of oil is too great, or the

supply of air is too small. This soot or lamp-black is deposited in

large chambers, from which it is collected. This class of lamp-black is

used for news and the commoner kinds of inks. For the better sort, a

black which is a product of the natural gas of America and elsewhere is

preferred on account of its greater density of colour.

Dry ColoursThe exquisite and brilliant colours known as anilines,

ranging over the entire prismatic spectrum, crimsons, reds, oranges,

yellows, greens, blues and violets, and including other colours such as

browns and purples, are to a certain extent denied to the inkmaker,

because many of them are fugitive, and therefore unworthy of use in "the

art preservative of art." The ink maker uses, for his finest inks, only

such coal-tar colours as are permanent, and he therefore relies for some

of his best results on colours which are not of this series. He betakes

himself to what we may describe as mineral colours, which include

vermilion, the chromes, bronze, prussian and ultramarine blues, or the

siennas and umbers, the two last belonging to, the group known as earth

colours, owing to the fact that they are obtained as earths and are not

manufactured. All dry colours are produced in the form of lumps or

powders, which require to be broken down or ground down before

incorporation with the varnishes.

Varnishes

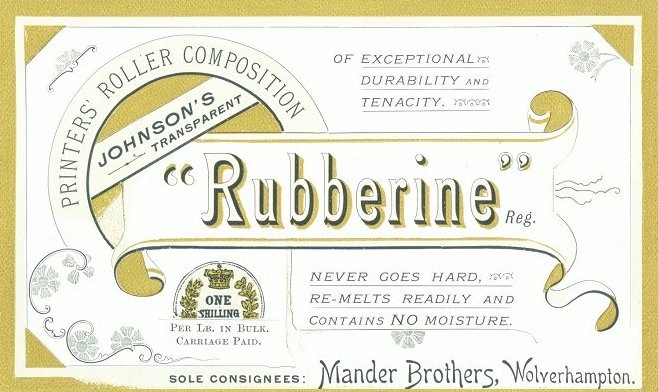

Many different varnishes are used by ink makers, but

the principal ones are those prepared from resin and linseed oils

respectively. The former is used for news and the commoner kinds of

inks, the latter for the better sorts. The best oil is genuine, well

matured, unadulterated, Russian Baltic linseed oil, costing a

high price, and the worst are the rough, ill-matured Calcutta

brands, which cost very much less, and which may be adulterated

to any extent. An ill-matured oil is easily discovered when it

is put into a varnish pot and heated, for it froths up and there

are deposited what are technically known as " foots." The

function of all varnishes is two-fold:

1. To act

as a vehicle or carrier of the colour.

2. To act as a drying agent.

Without the vehicle it would be impossible to

get the colour conveyed to the formes and blocks, and without

this drying agent, the printed matter would never be got into

the customers' hands in the marvellously short time in which

this is effected. Linseed oil, when subjected to prolonged

boiling at a high temperature, is converted into a varnish which

has an extraordinary affinity for oxygen.

Ink Prepared from Linseed Varnish

Varnish greedily, absorbs oxygen from the air, and this converts it from

a gummy substance into a compound which is solid at the ordinary

temperature of the air, the ink, in fact, is dry! This drying operation

is also assisted by the absorbent action of the printing paper and by

other means known to certain ink makers. Thick varnish, having absorbed

more oxygen during the boiling process, makes an ink having less drying

power than one made from thin varnish, but a thick varnish carries more

colour.

Varnishes for special purposes, such as the manufacture of bronze blue

ink, are "flared," which process consists in first heating the varnish

and then setting it on fire, thereby removing all greasy matter.

The colour is ground into the varnish in various proportions and for

various lengths of time, but always so that the finest subdivision of

the colour is obtained. With skilled workmen and ordinary care it is

next to impossible to make a badly ground ink with the latest ink

mills.

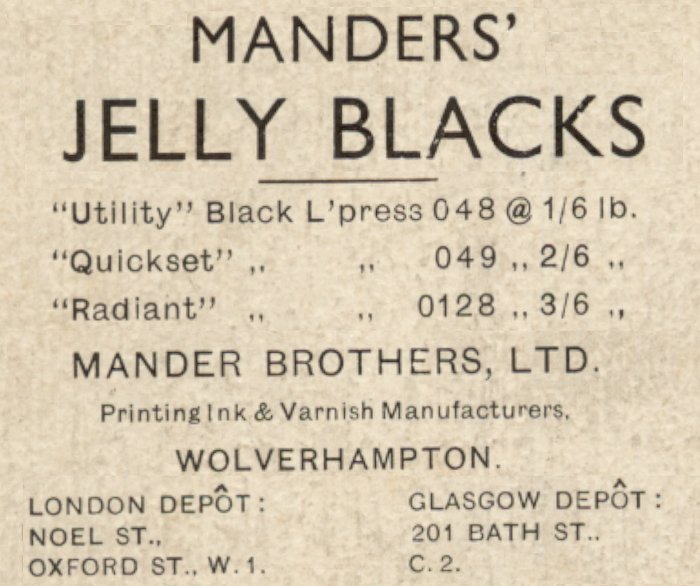

Letterpress Inks

Under this heading are included inks used upon

such dissimilar machines as modern high-speed rotaries and toy

platens, and for such different purposes as printing newspapers

or three colour illustrations. Whatever the machine, however,

and to whatever use that machine is put, the ink supply must

meet the following requirements:

|

1. |

It must

distribute freely, and be of the

right consistency and "tackiness." |

|

2. |

It must dry with

that degree of rapidity which the

speed of the particular machine and the

exigencies of the customer demand; and while it dries

with rapidity on the paper, it must not do so on the

rollers and slab. |

|

3. |

The ink must work cleanly, and

neither fill up the forme, nor cause set off. |

|

4. |

It must be of the greatest

density of colour if a black ink, and also of the exact right shade

if a coloured one. |

|

5. |

It must contain

the maximum weight of colour ground into the minimum weight of varnish,

compatible with the consistency required. |

Lithographic Inks

Lithographic inks are much stiffer than letterpress, and are

made from specially prepared varnishes; they require more power

to grind and contain more colour, and therefore usually cost

rather more. A lithographic ink cannot be too well ground for

the average high quality of work which is done with it on the

delicate surface of the stone. It is very important that

lithographic inks should be unaffected by the water used in this

process, and also that they should be non-acid, otherwise the

work on the stone becomes " eaten off." This last-named result

is sometimes caused, however, by badly ground inks.

The Mixing of Inks by the Printer

Unless the chemical composition of the dry colours

used is known more or less, it is very hard to say what inks will mix,

and the ink maker should be consulted. If a printer uses inks from one

maker only, it is an easy matter for that firm to tell him which inks

would, and which would not mix, since they would know what colours had

been used in the inks. But it would be necessary for anyone else to make

an analysis of the inks before being able to say definitely whether or

not they would be affected by each other. Supposing a printer was to mix

cadmium yellow with, say, flake white, he might be surprised to find the

resulting colour blacken. This, however, is what might be expected when

one remembers that cadmium yellow is the sulphide of cadmium and flake

white is lead carbonate, and that the lead sulphide resulting from the

mixture is black. Far and away the most common chemical action to be

feared by careless mixing, is mixing a lead colour with one containing

sulphur.

Some inks do not work evenly, and

this is specially noticeable in solid blocks, a mottled

appearance being produced. The degree of mottle depends a great

deal on the printer, some being able to get over the difficulty

better than others. Bronze blues, ultramarine blues and

inks made from earth colours seem the chief offenders. The cause

is to be found in the physical properties of the dry colours,

some seeming to have less affinity for the varnish and not

making so perfect a mechanical mixture.

The earth colours, being particularly hard and

difficult to grind, do not mix so readily with the varnish. The remedy,

given that the printer has failed, is to let the ink maker know all the

conditions under which the fault arose and to allow him to amend the ink

to suit the particular work. Variation of covering power in given

weights of ink occurs at times, and the cause lies again in the physical

properties of the dry colour, which cannot always be explained. Nothing

in the way of an alkali should be added to an ink, as many colours would

be decomposed. Bronze blue, for instance, would be decomposed to iron

oxide (rust). In the same way nothing having acid properties should be

added, as an equally bad result might be produced.

Whatever the ink, a thorough knowledge of the

nature and speed of the printing machine, the

kind of work to be done and the paper to be used

is essential before the ink- maker can supply a

satisfactory ink. It is an advantage if the ink

seller possesses a thorough knowledge of papers

and papermaking as he is then able to judge and

even to advise as to what ink will best suit a

given paper.

|