|

We were first shown the

fat lead-covered cables in which the

paper-insulated telephone wires enter the

apparatus room; a 2 inch cable carries 2,000

wires, grouped in various coloured divisions

presumably to prevent the wireman going mad

when he has to distinguish each circuit from

its neighbour and join them up correctly.

These leave their lead covering and are

connected to a large numbered-frame, each

pair having a fuse and a lightning arrester

fitted for the protection of the exchange

apparatus. A similar device is fitted at the

subscriber's end of the cable.

For the sake of

clarity, let us imagine that your telephone

is connected to a pair of these wires, and

that you want to call the works' number,

51226. You lift your receiver, the switchook

arm goes up, makes contact, and a line

switch at the exchange-end of your line

begins to hunt for the first vacant line to

the selector apparatus. This done, a low

buzzing in your receiver tells you that all

is set for dialling. (So rapid is this

operation that almost invariably the

dialling tone is heard as you place the

receiver to your ear.)

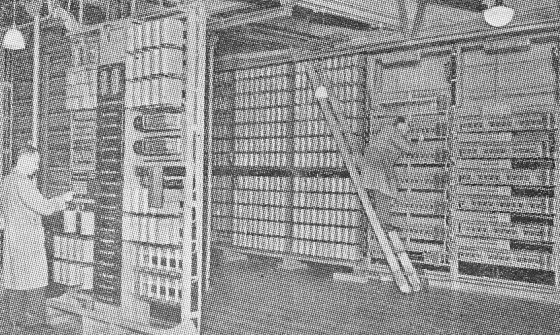

Banks of selectors.

Everyone is now

familiar with the outside of the dial: in

fact the exchanges have trouble with

children who enter call boxes and dial the

operator. The inside is not so simple. When

the dial is rotated a spring is wound which

returns it on release, governors regulating

the speed of the return. A cam plate with

ten teeth comes into operation on the return

journey, and by means of a contact breaker

sends a number of electrical impulses along

the line, corresponding to the number

dialled.

The selector to which

you are now connected is fitted with a bank

of a hundred double contacts, ten rows, with

ten in each row. Its vertical movement is

controlled from the dial. In this case, you

dial 5, and the "wiper" mounts to the fifth

row, and then automatically hunts along the

row for the first vacant contact. Those

already engaged are passed over, and it does

not come to rest until a vacant one is

found.

When this contact is

made you are connected to an outlet to the

group of lines whose numbers lie between

50,000 and 59,999. This group has another

set of selectors, each with its bank of 100

contacts. You dial 1, and the 'wiper' mounts

one, and again searches along the row for a

vacant line. This connects you to the group

of lines whose numbers lie between 51,000

and 51,999, and this group again has its set

of selectors and contacts. The digit 2 is

now dialled, and the selector mounts to the

second level, and swings round in search of

a disengaged line and connects you to the

51,200's group.

The selectors attached

to this group are different in action. You

dial the last figure but one of our number

(2), and the 'wiper' mounts two, but does

not rotate until the next figure is dialled.

As you dial 6, it moves six steps round the

contacts, and you are through to 51226 -

just like that.

That is the broad

principle-a progressive selection through

ranks of contacts by selectors controlled by

your movements of the dial, but many other

happenings must be provided for. When you

are through to the number required, power

must be transmitted to ring the wanted

subscriber's bell, and a tone produced in

your ear-piece to advise you that the

distant bell is ringing. If the number is

engaged, nothing happens at their end to

disturb conversation, but a high-pitched

burr, known as the "engaged tone," warns you

of the fact.

All these tones are

produced at the Exchange by varying the

frequency and period of interruption of an

alternating current generated by a small

motor-generator specially designed for this

purpose. Should this machine stop because of

failure of the town electric supply, or for

any other reason, an emergency set starts up

automatically without delay. This set is

driven by batteries, housed in the building,

which are capable of running the exchange

installation and the motor generators for

thirty six hours without re-charging. This

change over is hedged around with automatic

safety devices, which come uncannily to life

when required.

We were shown numerous

other attendant marvels: a device which,

once started, will carryon testing the

thousands of contacts used in the selector

apparatus until the proverbial cows come

home-or until a fault is found.

The gadgets on the

engineer's desk enable him to become a

veritable magician. When a fault is reported

he can plug into the delinquent line, test

it, feel its pulse, etc., without moving

from his chair. If the fault is outside the

exchange, he can, with a sensitive voltmeter

and some black magic, tell almost to a yard

where the fault is. So delicate is this

instrument that it was demonstrated how

breathing on the plug was enough to make it

register.

The dial speed of your

phone can be tested from the desk by an

ingenious device that registers the speed in

impulses per second. Nothing appears to have

been overlooked. Every eventuality has been

provided for, and if the apparatus requires

help, lamps glow to call the engineer's

attention. These not only call for help, but

indicate the urgency of the job; a white

light meaning something not quite so urgent

as a red.

The telephone exchange.

If the engineer has

slipped out to have one (which, however,

engineers rarely do), the call for help

takes the form of a bell. If your receiver

is left off for three minutes without a

number being dialled, the apparatus informs

the engineer, who applies a reminder in the

form of a high-pitched note which gains in

intensity the longer it remains un-noticed.

We were also taken over

to the manual portion of the exchange, where

operators control the calls not obtained

automatically, i.e., trunk calls, telegrams,

etc. The same painstaking efficiency was

noticeable here, and the electrical

call-timing gear had the magic touch, but

our capacity for surprise was by this time

exhausted. The crowning blow came when we

were told that the marvels we had seen were

already out of date and were being replaced

by more up-to-date equipment.

The whole party

expressed their gratitude to the Postmaster

for his kind permission, and to the two

guides who so ably piloted us through the

intricacies of that modern wonder, the

automatic telephone exchange. |