|

Tarmac - The First 80

Years

The firm was named after the road

surfacing material, developed and patented by Edgar Purnell Hooley in 1902.

By the early years of the twentieth

century, mechanised road transport was becoming commonplace.

The newly developed motorcycles, steam and petrol cars

needed a good flat surface on which to run, and Tarmac

Limited came up with the solution.

Background

One of the first really suitable road

surfaces for carriage wheels was macadam, named after John McAdam. It used layers of crushed stones, with thicker ones

at the bottom, and smaller ones at the top. Most iron

carriage tyres were about four inches wide. The top layer

of stones would be around three quarters of an inch across,

so that the tyres easily travelled over them. The roads were

built above the water table, and cambered, to allow rain

water to run off into ditches on either side.

By 1834 John Henry Cassell began using

his patented ‘Lava Stone’ which consisted of a layer of tar,

covered by a layer of macadam and sealed with a mixture of

tar and sand. It could be added to an existing macadam road

after scarifying the surface.

Tarmac uses coal tar, a once commonly

available by-product from the many town gas works that

heated coal in a closed retort. Approximately 10 to 15

gallons of coal tar were produced from each ton of coal. The

tar was transported from the gas works by canal boat, or by

road in large barrels, and used to produce a wide range of

products including creosote, disinfectants, foundry pitch,

liquid fuels, naphthas, protective coatings, and solvents.

A lucky accident

In the early 1900s the search was on

for a better material for resurfacing the roads. This

problem had been worrying Mr. Edgar Purnell Hooley, the

County Surveyor of Nottinghamshire. One day in 1901 he was

passing a tar works near Denby Ironworks in Derbyshire,

where a barrel of tar had recently fallen from a dray, and

burst open, covering the road with tar. In order to prevent

the sticky black mess from spreading everywhere, a

thoughtful person covered the tar with small pieces of slag

from the ironworks. Hooley noticed that the resulting

surface was remarkably durable, dust free, and had not been

rutted by passing vehicles. |

|

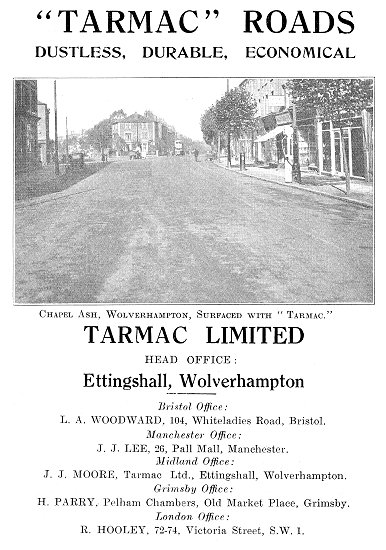

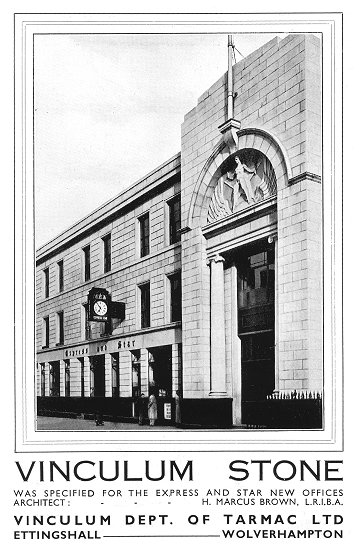

An advert from 1929. |

He realised that this material could

solve all of the road surfacing problems at the time, and

set about finding a way of producing it commercially. He

called the new material tarmac, short for tarmacadam,

meaning macadam mixed with tar. He took out a British patent

for the new material on 3rd April, 1902 (patent number

7796), and on 17th June, 1903 founded the Tar Macadam (Purnell

Hooley's Patent) Syndicate Limited.

His process consisted of mechanically

mixing tar and aggregate, which was spread over the road

surface, and compacted with a steamroller. Small amounts of

Portland cement, resin, and pitch were also added to the

mixture. Radcliffe Road in Nottingham became the first

tarmac road in the world. The new surface lived up to

expectations. It was hard wearing, and free from dust and

mud.

A factory to produce tarmac was built

at Denby, and on 26th July, 1904 Hooley obtained a US patent

for an apparatus for the preparation of tar macadam, which

improved the existing method of production. Later in 1904 he

visited the USA in order to promote the use of tarmac, but

unfortunately he was not a good businessman and had problems

selling the product. Because of lack of sales, the business

ran into financial difficulties, and in his absence

everything was put on hold. |

| The story could have ended there, but luckily

Wolverhampton MP, Sir Alfred Hickman realised the potential

of the new product, which could be made from the large

quantities of waste slag that were produced at his ironworks

in Ettingshall. He purchased the ailing company and

re-launched it in 1905 as Tarmac Limited, with himself as

Chairman. |

|

A new Era

The new company, Tarmac Limited became

an overnight success, and orders poured in. The new

management had completely turned the business around.

Sir Alfred died in 1910, and his son

Edward took over. The company continued to be

successful, making a profit of £4,752 at the end of his

first year as Chairman, which is nearly half a million pounds

in today’s money.

Because of increasing demand, the

manufacturing facilities had to be extended, and so in order

to raise capital, Tarmac Limited became a public company in

1913.

The factories at Ettingshall and Denby

were extended in 1914, and a new factory opened at

Middlesbrough, near to the North Eastern Steel Company. Around the same time several lucrative contracts were made

with county councils. |

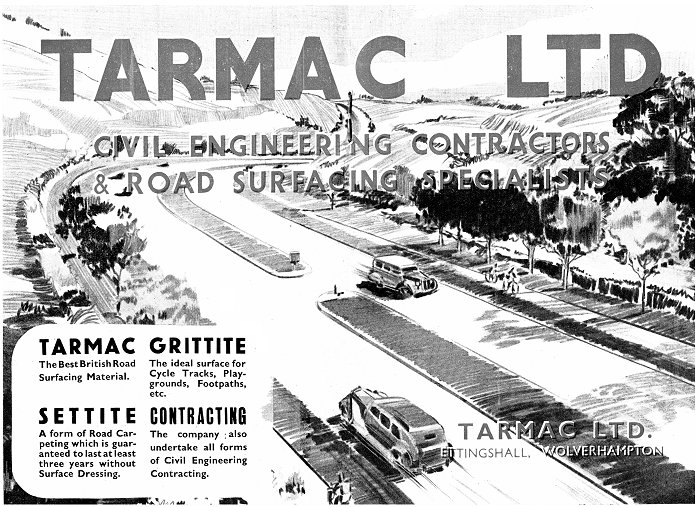

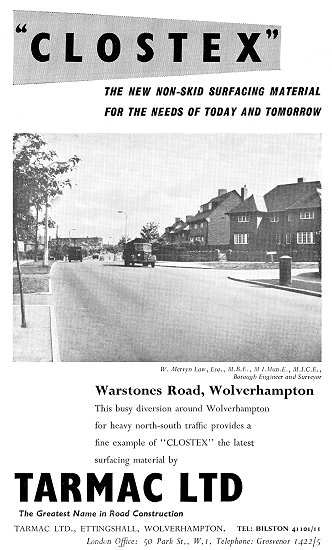

An advert from 1936. |

|

World War One

At the outbreak of war, the company

lost hundreds of men who joined the armed forces. This

greatly affected the road building programme and could have

led to the company’s demise. Orders rapidly decreased and

profits fell from £21,792 in 1914 to around £16,000 in 1918.

Luckily Tarmac’s Company Secretary Mr. D. G. Comyn had a

good relationship with the Head of the Road Board, Sir Henry

Maybury. This led to orders for large quantities of Tarmac,

which were despatched for military use. |

|

An advert from 1938. |

In September 1916 the Road Board

approached Tarmac to ask if crushed slag could be supplied

to help build urgently needed roads, to improve access to

the French battlefields. As a result large quantities of

crushed slag were shipped to the Front from Tarmac’s

Middlesbrough factory.

The shortage of labour continued to be

a problem for the company, but luckily the Road Board came

to the rescue, by supplying several hundred German prisoners

of war, who were each paid seven pence an hour. Camps were

setup to house the men at Bilston, Denby, and Middlesbrough.

By 1918, with the end of the war in

sight, Tarmac began to look forward to the future, and

expected a great increase in orders for new roads, and

resurfacing schemes.

The company leased a local slag heap from Lord

Dudley, and a steam-powered tipping waggon was acquired to

take the slag by road to the works at Ettingshall. |

|

The Inter-War Years

At the end of the war, orders poured in,

and Tarmac began a huge expansion programme. Sir Henry Maybury continued his relationship with the company. In

early 1919 the Board was informed that 750,000 tons of

tarmac would be needed over the next two years, for special

work alone. In order to meet the demand, Tarmac acquired

slag heaps and a roadstone quarry on the Welsh border. |

|

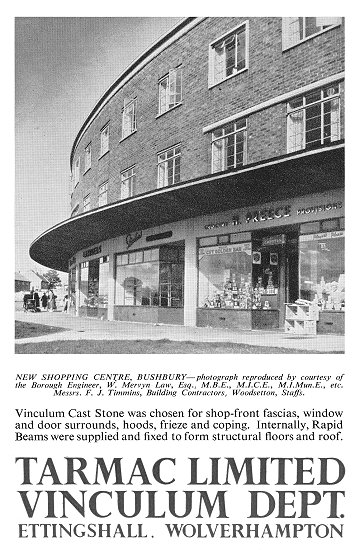

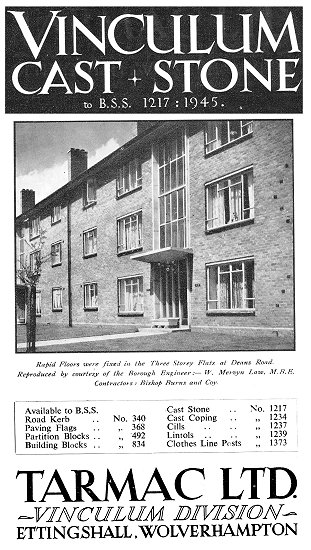

In the same year the company began to

diversify into the construction industry after acquiring the

patents for a system of construction using reinforced

Vinculum concrete, made from the company’s waste slag dust.

Contracts were acquired for the building of council houses

for Wolverhampton Corporation and the City of Birmingham.

The houses were extremely successful, and another order

arrived from Wolverhampton for a further twenty houses at

£720 each.

By 1926 around 190 miles of arterial

roads had been completed, including the country’s first dual

carriageway, the Kingston By Pass. Unfortunately 1926 was a

bad year for the company due to the general strike, the

recession, and a fall in the price of tarmac. In that year

Tarmac reported a loss of £49,576. Fortunately things soon

improved. In 1927 the after-tax profit was £44,576.

The late 1920s and the 1930s were years

of steady growth thanks to a rise in demand for the

company’s products. The average after-tax profits rose to

£57,000. There were two exceptional years, 1936 and 1938

when the after-tax profit rose to £80,000. The company’s

quarries were mechanised, and excavators began to be used to

load stone into railway wagons and road vehicles. Over the

years, Tarmac had acquired a large fleet of Sentinel steam

wagons, which were now being replaced with modern lorries.

New products appeared in the form of ‘Settite’, a bitumen

macadam, introduced in 1932, and ‘Asphaltic Grittite’, a

cold asphalt, introduced in 1938. |

An advert from 1929. |

|

By this time Tarmac had become a

household name. The Roadstone Department had production

facilities at Cardiff, Corby, Deptford, Ettingshall, Irlam,

Middlesbrough, Scunthorpe, Shoreham, and Skinningrove.

In the late 1930s the company formed a

Civil Engineering Department which would not only

concentrate on road building, but also on the building of

military airports, soon to become a necessity.

The Second World War

Because aircraft played a significant

role in the Second World War, new airfields were desperately

needed, and Tarmac began a huge airfield construction

programme. |

|

An advert from 1936. |

The company produced over five million

tons of road and runway materials, and as far as possible

introduced mechanisation to overcome labour shortages.

Nearly six million pounds worth of orders were received by

the Civil Engineering Department during the war.

The work

was often difficult and dangerous. On one occasion nearly

fifty German bombs fell on one airfield while it was being

built. Another airfield was machine-gunned by Messerschmitts

while building work was underway.

The Vinculum Department received a

large number of orders for air raid shelters. In the first

eighteen months of the war, around 50,000 precast concrete

units were produced, as well as concrete blocks for blast

walls. Building work was also carried out on gun sites, road

blocks, and defence projects.

When the end of war was in

site, Tarmac received an order for a special rush job, the

widening and strengthening of miles of roads in the south of

England, in readiness for the D-Day invasion traffic, which

travelled to the coast.

There were many other road building

projects carried out during the war. Britain’s roads had to

be brought up to scratch. One important project was the

building of the Maidenhead Bypass for Berkshire County

Council. |

|

The Post War Years

Tarmac began a re-investment programme

in readiness for the expected post-war boom. Over two

million pounds was spent over eight years on the

reconstruction and mechanisation of the existing production

facilities. The company was not disappointed. In 1946 the

pre-tax profit was £207,256 which by 1953 had risen to

£680,040. By this time Tarmac was processing over 2 million

tons of slag a year, and had become one of the most

important civil engineering businesses in the country. |

|

Tarmac built the first stretch of

motorway in the country in 1956, the eight mile long Preston

Bypass which became part of the M6 Motorway. This was

followed by the country’s first stretch of concrete surfaced

motorway, the St. Albans Bypass, which became part of the

M1.

In 1957 Tarmac Limited became a holding

company with three main subsidiaries: Tarmac Roadstone,

Tarmac Civil Engineering, and Tarmac Vinculum. In October

1958, merger talks were held with the tar distillers Crow

Catchpole, and the Amalgamated Roadstone Corporation. |

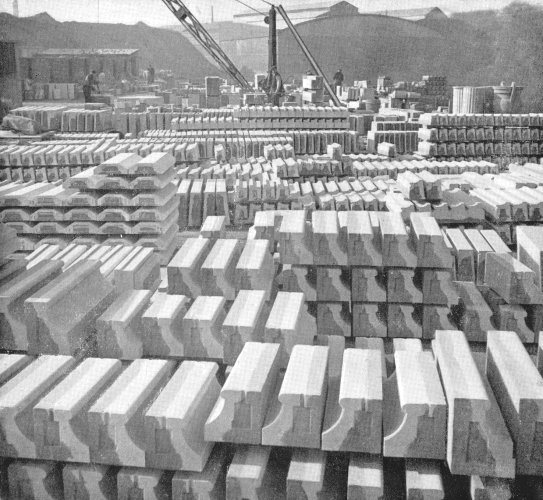

The Vinculum loading yard at

Ettingshall. |

| The talks broke down and the merger was abandoned. In

1959 however, Tarmac acquired Crow Catchpole to improve its

sales capability in London and the south east. In December

of that year, Tarmac acquired Tarslag, a company based in

the north east, which moved to Wolverhampton. |

|

An advert from 1948. |

|

An advert from 1953. |

Tarmac also acquired Rowley Regis

Granite Quarries Limited and their massive Hailstone Quarry

at Rowley Regis. The company now had a vast supply of stone

and so was less reliant on slag. After the acquisition, the

Industrial Division was formed, to serve both private and

public industries. Local area construction teams were also

set up. They became a vital part of the company’s

operations.

Profits continued to increase. By 1959

the annual profit amounted to £1,047,000, and the equity

capital had soared to £3,592,000. Tarmac’s new Managing

Director, Robin Martin, who was appointed in 1963,

instigated a massive expansion programme, which led to vastly increased

profits. By 1970 the annual profit was £3.8 million.

In the mid 1960s one of Tarmac’s major

projects was the building of the M5 Motorway.

Because of the decline in the availability of slag,

Tarmac acquired more quarries and several slag processors,

including: Taylors (Crook) Limited, slag processors in the

north east; William Prestwich & Sons, slag processors and

quarry owners, surfacing contractors, and foundry owners in

Sheffield; New Northern Quarries in the north west; Cliffe

Hill Granite in Leicestershire; and Hillhead Hughes, a

quarrying company with quarries in Derbyshire, Lancashire,

and North Wales. |

| Tarmac also secured its supply of bitumen by acquiring a

bitumen refinery at Ellesmere Port, jointly owned with

Phillips Petroleum of Oklahoma. A reliable bitumen supply

became essential by the late 1960s when town gas was replaced

by natural gas, so that coal tar was no longer available.

The first natural gas arrived from the North

Sea in 1967. |

|

The company's head office at

Ettingshall. |

|

In August 1968 Tarmac merged with two

rivals, Derbyshire Stone, and William Briggs, a company

based at Dundee, specialising in bitumen, building

materials, and building contracts. Tarmac also acquired

Amasco which then became known as Briggs Amasco. The new

group, the country’s largest roadstone and construction

group was initially named Tarmac Derby, but in 1970 the word

Derby was dropped.

1971 Tarmac acquired Limmer and

Trinidad, a London based quarry products firm, with an

asphalt lake in Trinidad. Tarmac then became the largest

road surfacing contractor and blacktop producer in UK. The

acquisition included the firm of

Fitzpatrick & Son, which for many years held all of the

paving contracts for the City of London and the City of

Westminster.

Tarmac’s expansion

continued. In February 1973 the company acquired Mitchell

Construction Holdings, and its subsidiaries including

Kinnear Moodie, an expert tunnelling company. This led to

contracts for parts of the Fleet Line underground network in

London, the first tunnel under the Suez Canal in Egypt, and

the Brighton sewer outfall. The company also carried out

construction work on parts of the Majes Project in Peru,

which included the building of tunnels, canals, and

reservoirs to transport water from the Andes to irrigate the

Majes Plain. Other projects included concrete oil production

platforms, and civil engineering work on the Thames Barrier. |

An advert from 1956. |

|

From the Glasgow Herald. 14th

February, 1973. |

|

From the 1972 Wolverhampton Handbook. |

By this time the company had vast stone reserves. Tarmac

owned over a hundred quarries, and could potentially remove

over 3,300 million tons of rock, enough to supply the

country for about thirty years. The stone was mainly

quarried for concrete, building and road foundations, rail

ballast, sewage filter beds, sea and river defences, and

road surfacing.

There were also sand and gravel pits, and a dwindling

supply of furnace slag. |

| The company’s limestone quarries supplied ground

limestone for use as a soil neutraliser, and stone for

cement, iron and steel production, fillers, and for the

sugar, glass, rubber, and plastics industries. Tarmac also

mined natural rock asphalt in France and Switzerland, which

is a naturally occurring mixture of limestone and bituminous

crude oil. |

|

An advert from 1951. |

|

An advert from 1956. |

| The road building and resurfacing part of the business

continued to thrive. Products were available with a wide

range of characteristics. There were skid resistant

surfaces, heat resistant surfaces, airport runway surfaces,

and many more. The company also had a large involvement in

the country’s motorway building programme, and built roads

throughout the world, in all kinds of terrain, from

mountains to deserts. |

|

Careers at Tarmac in 1967. |

The home building side of the company

expanded dramatically in early 1974 when Tarmac acquired

McLean Homes. Up until then, Tarmac Homes, the original

private house building company, had been a mediocre

performer, but that soon changed.

After the take-over, Eric Pountain,

McLean’s Managing Director, ran the house building division.

Under his leadership it went from strength to strength,

producing around 2,000 houses a year. By the end of the

1970s McLean was building 4,000 houses a year, and

substantially contributed to the group’s profits. It soon

became the country’s biggest house builder, and in 1979 Eric

Pountain took over as Managing Director for the whole Tarmac

Group.

There were other take-overs in the

1970s. In 1976 the civil engineering part of the company

expanded with the acquisition of the building company

Holland Hannen and Cubitts which had been involved in many

important building projects.

Tarmac set up a number of teams to work

as local contractors, both at home and abroad. The expansion

continued with the acquisition of Thomas Lowe & Sons,

followed by the acquisition of Alexander Turner of Scotland

in 1977. |

|

An advert from 1965. |

|

An advert from 1968. |

|

The company became one of the largest

waterproofing businesses in the country after taking over

Permanite, Britain’s biggest roofing felt manufacturer.

Under Tarmac’s wing, the firm’s products included bituminous

roofing felts, mastic asphalts, and bitumen polymer based

sheeting. Another member of the group, Coolag, enabled

Tarmac to produce a variety of thermal insulation products

including rigid polyurethane, and polyisocyanurate foam,

ideal for roof and wall insulation.

Expansion continued in 1980 when Tarmac

acquired Briggs' Dundee oil refinery and greatly increased

its output.

An advert from 1985.

The company grew from small beginnings

into a vast group, and since the 1980s has continued to

expand. In recent times it has itself been taken over, to become

part of one of the largest construction companies in the

world. |

|

Return to

the

Entrance Hall |

|