Stevens Brothers

(Wolverhampton) Limited

| The Stevens brothers must have been devastated after the

closure of A.J.S. in October 1931. They lost nearly

everything in the process, and yet decided to roll up their

sleeves and start all over again from the beginning. Luckily

they still owned their old Retreat Street premises, which in

the intervening years had been used by the Stevens Screw

Company Limited. Working on a shoestring they set up a new

company called Stevens Brothers (Wolverhampton) Limited, in

May 1932. The directors were the five Stevens brothers;

Harry, George, Joe, Jack and Billie. Working around the

clock, and assisted by a number of unpaid volunteers, they

managed to design and develop the 'Stevens Light Commercial

Vehicle', a three wheeled van.

| Read about the

Retreat Street factory |

|

|

|

The Stevens 3-wheeled van that can be

seen at the Black Country Living Museum. |

It was based on a prototype three wheeled vehicle, built

in 1921 at the A.J.S. works on Graiseley Hill, that had two

wheels at the front and one at the rear.

The Stevens van used motorcycle technology, with a single

wheel at the front, carried on heavy duty motorcycle forks.

There was a steering wheel, connected to the front wheel

by two roller chains, and a water-cooled single-cylinder,

side valve, Stevens 588c.c. engine, with dry sump

lubrication.

The rear wheels were chain driven from a Burman 3 speed,

plus reverse, gearbox. |

| The van was fitted with a foot operated kickstart lever,

and a throttle, mounted in the centre of the steering wheel.

Initially a full-width bench seat was fitted but soon

replaced by a large motorcycle saddle. The bodies were

bought-in and had a capacity of 91cu.ft.

Initially no front doors were fitted, they became

standard at a later date. The vehicle weighed 7.75cwt. and

could carry 5cwt. It had a top speed of about 45m.p.h. and

sold for £83.

From late in 1932 the vans were also built in London by

Bowden (Engineers) Ltd., who had a manufacturing agreement

with Stevens.

The vans sold quite well, and a building across the road

in Retreat Street was rented from storage and furniture

removers, S. Lloyd & Sons, so that production could be

stepped-up.

The vans were assembled in batches of six. When one batch

was sold, work could begin on the next batch. |

Looking through the back doors of the Stevens

van at the

Black Country Living Museum. |

|

A close-up view of the steering

wheel and engine in the Stevens van at the Black

Country Living Museum. |

An improved version was launched in

October 1935 with an improved drive. The earlier chain

had a habit of breaking, and so it was replaced by a drive

shaft, which required the repositioning of the gearbox.

The improved van could now carry 8cwt.

and sold for £93.9s.0d. and was also available as an open

truck.

|

| Read

about the new version of the van |

|

A recently discovered Stevens three-wheeler which

is about to be restored. Courtesy of Ken Norton. |

|

Because the company ran on a

shoestring, the expensive up-to-date machinery that had been

in use at Graiseley Hill, was not affordable. As a result

everything had to be finished by hand.

The late Geoff Stevens, who worked at

the company during the early days, remembered making cams by

roughly cutting out a circle, then hand filing it to the

correct profile.

Production continued until late in

1936, by which time sales declined, because customers

preferred the comfort and convenience of a 4 wheeled van.

It is believed that around 500 Stevens

vans were built, of which only a few are known to have

survived. |

An advert from April 1933. |

A drawing of the van. Courtesy of the late Geoff

Stevens.

|

|

|

|

A front and rear

view of the Stevens van that's in the collection at the

Black Country Living Museum. |

| Stevens Brothers also produced a number

of engines for E. C. Humphries of the O.K. Supreme Company,

and A.J.W. using the 'Ajax' name.

It was clear that the

Stevens company could not support all five directors, and so

in 1934 Joe and Jack left to start their own company,

Wolverhampton Auto-Machinists Limited, which carried out

jig-boring, and produced jigs, and fixtures for the

engineering trade.

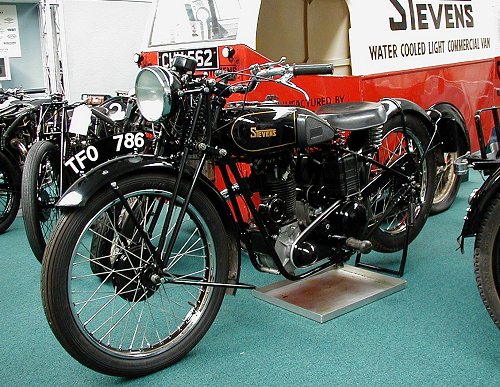

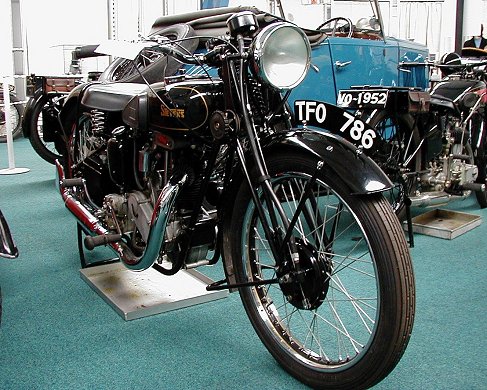

The Stevens Motorcycle |

The Stevens 250c.c., o.h.v. machine

that's on display at the Black Country Living Museum, Dudley. The machine was built in 1934. |

In March 1934 the three brothers

re-entered the motorcycle market with two new machines,

designed by Harry Stevens.

They were called the 'D.S.1' and the 'U.S.2', and were

sold using the 'Stevens' name.

Luckily, after the sale of A.J.S., Matchless had left some

jigs and parts behind, which were used in the manufacture of

the new machines.

The machines were powered by a 250c.c., single cylinder,

overhead valve engine, that was very similar to ones used in the later

A.J.S. machines.

The 'D.S.1' had a down-swept, chromium plated exhaust

pipe, whereas the 'U.S.2' had an un-swept exhaust. |

| The machines were fitted with a 4 speed Burman gearbox

and a multiple plate clutch, Lucas 'Magdyno'

ignition, with the magneto mounted behind the cylinder, and a 6 volt lighting system.

Other features included an oil pump fitted in the fully

enclosed oil bath chaincase, a 3 gallon black petrol tank

with gold lining, and a total loss lubrication system, with

the rockers lubricated by grease. The rockers were mounted

on side plates like the much earlier A.J.S. ‘Big Port’

engines. |

| The engine was mounted vertically in a modern twin

downtube frame. Both the handlebars and the seat were fully

adjustable.

Both models were

priced at £51.

Due to lack of money the company operated on a 'hand to

mouth' basis and built the motorcycles in batches of 12.

The brothers couldn't afford to start work on a new batch

until the last batch was sold.

The motorcycles were assembled in the building across the

road that was rented from the furniture removers and storage

company, S.

Lloyd & Sons. |

A close-up view of the Stevens machine

at the Black Country Living Museum. |

|

Another view of the Stevens machine at

the Black Country Living Museum. |

Harry Stevens had an office with a drawing board in the

building, where he could work quietly without being

disturbed.

The building was later acquired by Rediffusion, the original

cable radio and television company.

The machines were road tested by a number of popular

motorcycle magazines and given excellent reviews. They were

described as ranking amongst the best, which is a tribute to

the Stevens family, especially considering the primitive

conditions at Retreat Street. |

| A small number of minor improvements were made for the

1935 season and two 350c.c. models were launched. They were identical to the earlier machines except for a

larger engine, and different gear ratios.

The first model, the 'H.L.3' had a high level exhaust

system, the second, the 'L.L.4' had a low level exhaust.

The machines had a top speed of 67m.p.h., and excellent

brakes. Both machines were priced at £52.

In April 1935 a 500c.c. machine was

added to the product range. It had a heavier frame, a longer

wheelbase, and fittings for the attachment of a sidecar. It

sold for £63. A competition version was also available, for

£69. It had a close ratio gearbox and narrow mudguards. |

Trevor Davies astride the museum's

Stevens machine. |

Tommy Deadman on his Stevens motorcycle in

1935. That year he had a very successful season and is seen holding

one of his many trophies. Courtesy of the late Jim Boulton. |

In the autumn of 1935 cosmetic changes

were made to the 500c.c. model. The lining on the tank was

given a thin blue edging, as were the black centres of the

chromed wheel rims, and the old fish-tailed silencer was

changed to a less-swept megaphone silencer. The

machines were proving to be popular, about 200 were produced

each year.

The brothers decided to try and boost sales by

entering their machines in competitions. Tommy Deadman, the

chief tester, entered many competitions and was very

successful on his Stevens machine.

The 1937 machines included a larger

petrol tank, and a megaphone style silencer. Motorcycle

production reluctantly ended in the summer of 1938 when the

country was preparing for an inevitable war. The brothers

realised that during the war, civilian motorcycle production

would cease, and a small company like theirs would not

be able to obtain contracts to build motorcycles from the

War Department. As a result they decided to concentrate on general

engineering work.

During the five years or so of motorcycle

production, around 1,000 Stevens machines had been built.

The last two Stevens motorcycles to leave the works were

specially built for

two members of the Stevens' family, Alec, who was Joe's son

and Jim, Billie's son. |

| In 1938 Harry designed an engine for

George Brough of Nottingham who built the famous Brough

Superior motorcycles. The engine was for a special high quality

machine called the ‘Brough Dream’, later called the ‘Golden

Dream’.

It was to be displayed at the 1938 Motor Cycle Show at Earls Court.

The 1,000c.c. engine and 4 speed

gearbox was completed on time, but only a single prototype

machine was built. |

A Stevens engine. Courtesy of the late

Jim Boulton. |

|

A Stevens Brothers advert in the

November 1938 edition of Flight Magazine lists the following

trade services: light engineering work, machined parts,

assemblies, wire & tube manipulators, welding, light

presswork, etc.

By the late 1930s age was catching up

with the brother’s father, Joseph Stevens and so his

youngest son Billie took over the running of the Stevens

Screw Company, which by the early 1950s employed over 70

staff. Production consisted of hundreds of different small

parts including bolts, nuts and screws, in ferrous and

non-ferrous metals, made from the bar.

In 1938 Billie’s son Jim began to work

at Stevens Brothers after leaving school.

During the Second World War Stevens

Brothers manufactured and machined components for most of

the leading aircraft companies, including Bristol and Fairey

Aviation, Avro, Handley Page, etc., and were sole manufacturers

of the torpedo depth setting gear fitted to every Fairey Swordfish torpedo

bomber. At the time Stevens Brothers were much sought after

to take on jobs that other businesses could not, or would

not do.

After the war, the firm carried out light

engineering work, and also produced office equipment for Ellams Duplicators, under licence.

In the 1950s Jim Stevens took the

decision to sell Stevens Brothers (Wolverhampton) Limited.

By this time his father and uncles had died, and the sale

would allow him to concentrate on the running of the Stevens

Screw Company Limited.

Stevens Brothers was acquired by Leo

Davenport, a successful businessman, who had previously been

a successful competition rider for A.J.S., both at home and

abroad. His father Tom Davenport had also worked for A.J.S.

at Graiseley Hill, where he held a managerial post. |

Retreat Street Works in the 1980s. Courtesy of the

late Geoff Stevens.

|

Stevens Brothers continued to be

successful under Leo. Everything in the works had to be just

right. In the machine shop stood a row of capstan lathes

which were always kept in immaculate condition. Leo also did

work for the Stevens Screw Company. Two other businesses

were run from the Retreat Street premises. The first, Jones

and Goodare was owned by the Stevens Screw Company, the

second, Lombard Products, Midlands Limited was owned by Leo

Davenport.

All of Stevens Brothers machinery was

driven from overhead line shafting, powered by an electric

motor that stood in the corner of the machine shop. Every Friday at 5 o’clock the machines were

shut off, and thoroughly cleaned. Cleaning time ended at

5.30 when the foreman, Bill Priest made an inspection.

Between 30 and 40 people worked in the machine shop. The

stores were run by Jack Bennett who also drove the company’s

van.

In 1992 it was all over, the end of

an era. The factory was acquired by Engines Limited,

and later W. Hopcraft & Son Limited, monumental masons.

Although the buildings still survive, they have been empty

for several years.

|

|

Return to the

previous page |

|