General Metal and Holloware

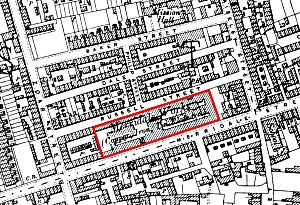

The information about the firm contained on this page is transcribed from a document, held in Bantock House Museum, Wolverhampton. It is a hand written document, dated July 1979, and appears to be notes taken in an interview with Mr. V. Tuckley. (We are obliged to Helen Steatham of Bantock House Museum for giving us access to this document). After this transcript first appeared here we heard from John Tuckley that this interview was given by his father, Victor Tuckley. Victor came from a long line of locksmith Tuckleys; his grandfather, Phillip, was one of the last of them. His father, William Henry Tuckley, worked at Jones Bros.. Phillip moved to Zoar Street, from Willenhall, just round the corner from Loveridge's works. His grandson Victor was probably apprenticed as a tinsmith or sheet metal worker. When Loveridge's closed Victor moved to Wishaw, Scotland, where he worked in bus manufacture, presumably with either Stewarts or McKay and Jardyne. After the War he operated his own sheet metal working business in Mander Street. When that closed he went to Coventry and worked on car bodywork. Later he joined ICI Marston making specialised fuel tanks for aircraft. Victor Tuckley died in 1987. It is very helpful to have the provenance for this document and information about Victor Tuckley. We are obliged to John Tuckley. The following information was relayed by Mr. V. Tuckley, the last man to be apprenticed in the Loveridge factory. Apprenticed in 1923, aged 14, he remained with them until the firm's closure in 1927. Manufactures: cash boxes, deed boxes, "quality ware", travelling boxes, kettles, hot plates and candle extinguishers. Art metal work: pewter mugs, etc. Supplied the Savoy Hotel with copperware: hot plates, salt cellars, saucepans. Samuel Loveridge: figurehead only - rarely seen in factory. Loveridge family monuments in Codsall Church. Mr. Gough: general manager. Working day: 8.00 - 5.30. Saturdays 8.00 - 12.30. Division of factory: tin-plate working and papier mache workers segregated. Papier mache: by this time quite small - only two women employed. After "blacking" papier mache was decorated by same man who decorated tinwares. Workshop barred from other workmen. Decorating: two painters were employed - one of whom was very old. Some cash and deed boxes were decorated, often with dragons, etc. and some were monogrammed to order. Transfers were supplied by a stationer's in King Street. (Mr. Tuckley thought it might have been Whiteheads but wasn't sure. Certainly the stationers Clark & Evans were situated in King Street). As an apprentice it was one of Mr. Tuckley's duties to take a truck to King St. to collect the transfers. The decorating shop was known as the "Japanning Shop". Blacking was always done by women. Gold leaf kept in offices. The decorators had their own store and worked over the entrance in the same part of the building as the papier mache ladies. Very fine brushes used for painting chinamen. Apprenticeships lasted five years. At the peak of the industry(?) there was one apprentice to every 5 men employed. One of the duties of the apprentices was to keep each department supplied with coal. Altho the factory made coals hods and scuttles, the coal was carried, often up 3 flights of stairs, on an old tin tray. The factory and its layout (with reference to the view of the building shown in the Loveridge trade catalogues). Front of factory. Main section, over entrance, given over to offices. The two papier mache ladies occupied an area upstairs and to the right of the main entrance. Area to the left of main entrance, largely derelict. (*As machines took over, less and less of the factory was used). End block on far right of front building was converted to houses - for whom it is not certain. The block which joins the main entrance to the rear block, housed the stoves. The stoves were arranged 8 to a row, were approx. 15' long, 5' - 6' wide and 6' - 8' tall. Each stove had an iron door. Obviously the stoves were never allowed to cool completely, only enough to allow the "stove enamellers" to walk in and stack the stoves, The stoves were loaded from trucks which were wheeled into them by the "stove enamellers" who were on piece-work and who were always women. Near the entrance (on the ground floor?) was the showroom. Long side of the factory (facing Russell Street) Given over to tin-shops, the ground floor divided into small shops. "Tin shop" (i.e. the store) at right of block. The sheet metal was generally stored in sheets 2' x 3'. Beside the tin-shop was a staircase, on the other side of which worked 2 "wheelers". Next to the wheelers' shop was the little press shop, used for stamping small items such as kettle knobs. The presses were operated by women. Their shop was in the centre of the block, at the end of the linking block. Next to this was the "blacksmith's shop" where chased copper articles were made. The top-shop, i.e. top floor, was occupied by the apprentices. Front of Building Altho much of the building to the left of the entrance was derelict, 3 floors were in part occupied by the tin-smiths - the middle floor or middle shop being used for the coarser work.

General "Draw-wiring" i.e. drawing the wire from the edge of a wired tray. Women were employed at stores and hand presses. (Mr. Tuckley described them as "coarse women, far from ladies", quite unlike the two papier mache women "who were ladies"). Materials and sources:

Packing: articles wrapped in paper and packed in saw-dust in tea chests which the apprentices collected from local grocers, Despatched by rail. Close of factory: Loveridge's lost orders because of their refusal to mechanise and modernise and were ultimately forced to close down. Furthermore there was nobody to take over the firm, and by this time John Marston (now part of ICI) were employing all the best sheet metal workers. [*"Tinmen's Rest" a section of the canal in Whitmore Reans where many tinsmiths committed suicide.] In using the above document it must, of course, be remembered that these were the recollections of a 70 year old man, recalling matters from more than 50 years before; and those recollections were then filtered through an (unknown) interviewer. |