| The town of Wolverhampton, West Midlands, is justly

proud to be a native place of an interesting 18th

century artist, Joseph Barney. His two altar pieces,

'The Deposition from the Cross' (1781) and 'The

Apparition of Our Lord to St Thomas' (1784), have

been preserved in Wolverhampton, well-known, and can be

seen today at St John's Church and at St Peter & St

Paul's Roman Catholic Church. |

|

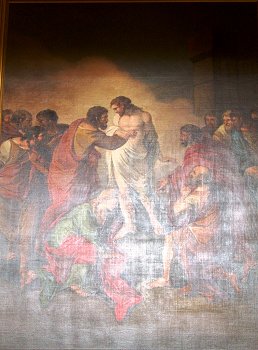

Joseph

Barney. The Deposition from the Cross. 1781.

St. John’s Church, Wolverhampton. |

|

|

|

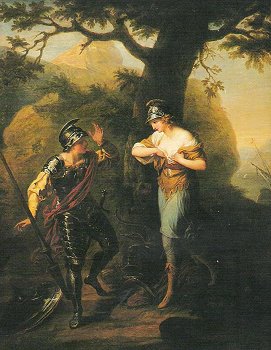

Joseph

Barney. The Apparition of Our Lord to St

Thomas. 1784. SS Peter & Paul’s Roman

Catholic Church, Wolverhampton |

|

|

Joseph Barney. A Blind Musician. Late 18th

C.©WAG. |

During Barney's life time, his artistic achievements

were respected and praised, at least, locally. In 1798,

Stebbing Shaw, mentioning 'The Deposition from the

Cross' in his 'History of Staffordshire'

called Barney a 'native genius' of Wolverhampton[1].

In the collection of Wolverhampton Art Gallery, there is

his charming sentimental pen and ink drawing 'A Blind

Musician' which gives some additional idea of

quality and versatility of Barney's works. |

Unfortunately, a detailed monographic research into

his life and work has never been undertaken. Modern

historians of the 18th century and museum curators

usually come across his name in the references sections

of books on Angelica Kauffman, where he routinely is

described as a pupil of Antonio Zucchi and Angelica

Kauffman, and a 'fruit and flower painter to Prince

Regent'.

Fruit and Flower Painter?

Such a description should be challenged because Barney's

altar pieces immediately and clearly indicate his

ambition to become a historic painter.

Barney's characteristic tag as 'Fruit and Flower

painter' appeared in Michael Bryan's

'Biographical and Critical Dictionary of Painters and

Engravers…', the

first edition of which was indeed published during

Barney's lifetime. Moreover, the comparison of different

Wolverhampton trade directories and other sources[2]

helps to identify Joseph Barney-artist as a son of

Joseph Barney Senior, a japanner and a partner of

japanned ware business of Barney & Ryton between

1780-1802. |

| Thus we can conclude that indeed he received some

initial artistic training in painting fruit and flowers

which related to his father's japanned ware business.

When in or before 1774 Joseph Barney came to London he

received from the Royal Society of Arts 'a Silver

Palette for a drawing of flowers'

[4]. This

award, however, indicates his initial training in his

native town but not his established specialization.

In 1883, George Wallis wrote that Barney 'visited

the old friends, my relatives, who, as a boy of 13 or

14, I have heard speak of him as coming from London and

/…/ of his great ability as flower painter.'

[5]

In 1938, a 'flower painting by Barney' was

offered to Wolverhampton Art Gallery by George Staveley

Hill, but not acquired.[6] It seems that it might have

been not the oil painting, but a magnificently painted

japanned tray which was described and reproduced in

black/white by G Bernard Hughes in 1950, and belonged at

that time to Mrs E. Staveley-Hill.[7] |

Joseph Barney. Flower Piece which belonged to Mrs E.

Staveley-Hill. Present location unknown. |

Flower

Piece wrongly attributed to J Barney

and dated 1840s-1850s. Image: Witt Library. |

However, the analysis of the 75 works which he

exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1784 to 1827, shows

that only seven ones dealt with fruit and flowers. From

49 works shown at the British Institution from 1806 to

1839, only fifteen depict these subjects.

The file for Joseph Barney at the Witt Library

contains 14 images of his works, all of which, except

only one, are figurative. This only flower painting is

dated 1840s which obviously contradicts with dates of

Barney's life.

A pair of portraits by Joseph Barney of Mr & Mrs

Barney of Wolverhampton, the artist's father and mother,

were offered for sale in 2003.[8]

From the close cap of Mrs Barney and the full-bottomed

wig of Mr Barney they can be dated 'early 1770s'. |

|

|

|

|

Joseph Barney. Portraits

of Mr and Mrs Barney, parents of the artist. C.1770s.

Private collection. |

At the same sale, the portrait of

James Barney, brother of the artist, appeared.[9] If these portraits

are indeed by Joseph Barney, they introduce his early exercises in

portraiture. Among his later works there were no less than three

other portraits - of Mrs Barney, possibly his wife (1803), of Mr

Hicks (1813) and of a Young Lady (1817). All these works demonstrate

his strong inclination towards historic and religious painting and

experiments with portraiture.

Pupil of Angelica Kauffman?

Published sources keep repeating after Bryan that Barney 'studied

under the Italian decorative painter Antonio Zucchi (1726-1795) and

Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807), exhibiting from their London address

in 1777. His early work favoured the same neo-classical style of

decorative and historical painting.'

[10] This information also should

alert the historians: both Zucchi and Kauffman were figirative and

decorative artists, did not paint fruit and flowers, and

consequently did not train in this genre.Barney did indeed study with Antonio Zucchi, as in 1777 he exhibited

at the Society of Artists from 'at Mr Zucchi's, John Street,

Adelphi'. But so far there is no documentary evidence of Barney

studying with Angelica Kauffman - as Zucchi and Kauffman never had

the same address in London. She lived at 16, Golden Square, closely

chaperoned by her father. They started to share the address after

their marriage in July 1784, but they left England for the Continent

several days later. Of course, living in London and being a part of

artistic scene at Antonio Zucchi's house, Barney must have known

Angelica Kauffman as a co-founder of the Royal Academy of Art and a

highly popular artist, and even been acquainted with her directly,

but this does not make him Kauffman's pupil.

The very fact of Barney's association with Zucchi also confirms his

development as a historic painter. The Gold Palette was awarded to

him in 1781 for historical drawings.[11] Among five Barney's works

exhibited at Society of Artists in 1777-1783 from Antonio Zucchi's

house in John Street, Adelphi and from Wolverhampton, two paintings

- 'Portrait of a Lady in the Character of the Comic Muse' and

'Una,

from Spencer's Fairy Queene' - reflect his interest in historic

genre, and reveal intellectual and artistic atmosphere of Zucchi's

studio: at that time, the Spencer's poem was extremely popular

responding to the romantic longings of the generation. The Faerie Queene inspired paintings by Benjamin West and Henry Fuseli. Barney

would return to the Spencer's poem later in his life, exhibiting in

1827 'Mercy and the Red Cross Knight entering the Cave'.

On the whole, Barney's spell in London in the 1770s was marked by

the Silver and Gold Palettes, exhibiting at the Royal Academy and

the Society of Artists, mixing with the leading artists of the time.

It can be considered as a promising beginning of a successful

artistic career.

Back in Wolverhampton. Mechanical paintings for Matthew Boulton

Barney returned to Wolverhampton in about 1779, as in August 1779 he

married Jane Whiston Chambers[12]

at St John's chapel, Wolverhampton,

for which two years later he would paint the altarpiece. In October

1780, their first child was born. It was imperative for him to

obtain means to support his new family. Interesting, that despite

his initial training and obvuios painting skills, he he did not join

his father's japanned business which would bring financial income,

but not independent artistic career and reputation.

In 1970, Eric Robinson and Keith R. Thompson, analyzing available

information on Matthew Boulton's mysterious mechanical paintings,

revealed Barney's collaboration with the Soho factory. business[13],

although in their paper Barney remained an under-researched

background figure without any mentioning of his own works .

|

| The process of production of the mechanical paintings remains a

mystery even today, despite the efforts of several generations of

the researchers. It seems that with the help of some mechanical

device, the image of original painting was printed on primed paper

or canvas and then finished manually.

It was this last stage of the

production where the professional artists were involved. Barney

started to collaborate with Soho no later than in November 1779[14].

The nature of work and the payment were obviously

lower than his artistic ambitions and abilities, and

appeared very disappointing financially. It seems that

on the early stage of the enterprise he had to correct

and finish mechanical paintings after unskilled

apprentices. |

|

Original for

a mechanical painting finished by Joseph

Barney: Benjamin West. Erasistratus the

Physician Discovers the Love of Antiochus

for Stratonice. 1772. ©Birmingham Museum of

Art, USA. |

|

Original for a mechanical painting finished by Joseph

Barney: Angelica Kauffman. Telemachus on His Return to

His Mother.1770-1780. ©Mead Art Museum, USA. |

James Keir wrote: 'Mr Barney, not having any work

for sale, proposes to begin some painting for your own

account, which he says you ordered him to do. I desired

him to let me know the prices of the several pictures

you spoke of. /…/ The prices /…/ are lower than any he

has hitherto done. We acquainted him that the business

was not such as could afford his prices, and therefore

he must not depend altogether on Soho for employment. He

consented to work by day to retouch the boys' pictures,

at 10/6 per day.'

[15] The prospect 'to retouch boys'

pictures' was hardly satisfactory. Indeed, his

1781-1782 correspondence with the Soho employee John

Hodges and Francis Eginton shows that this retouching

took rather short time. Barney's further involvement on

the process and his associations with fellow artists,

particularly with Benjamin West, would be much more

active, creative and multifaceted.[16]

|

|

Also, it is worth noticing, that along

with Joseph Barney, at least two other artists worked on

mechanical paintings. Each of them had some

specialization, and Barney's one emerges as figurative

historic compositions.

From several contemporary inventories of mechanical paintings[17] and

contemporary correspondence the following mechanical pictures can be

identified as finished by Joseph Barney:

'Hebe' (Portrait of Miss Meyer as Hebe), after Sir Joshua Reynolds;

'The Physician Erasistratus discovering the love of Antiochus for

Stratonice' and 'The Death of General Wolfe', after Benjamin West;

'The Forge', after Joseph Wright of Derby;

'The Wise Men's Offering', after Antonio Zucchi;

'Penelope weeping over the Bow of Ulysses';

'Calypso mourning the

departure of Ulysses'; 'Cupid bound by the Graces' ;

'Cupid

Struggling with the Graces'; 'The Graces Dancing',

'Faith', 'Hope',

and 'Charity', 'St Catherine' (possibly

'Marriage of St Catherine of

Alexandria'), 'Telemachus at the Court of Sparta';

'Telemachus on

His Return to His Mother'; 'Rinaldo and Armida'; 'Time and Cupid',

'Imbaca

discovering herself to Trenmore', all after Angelica Kauffman. |

Original for a mechanical painting finished by Joseph

Barney: A Kauffman. Trenmore and Imbaca, from

‘Ossian’.1773.

© Private collection. |

| It is probably from his finishing of mechanical paintings the

conclusion emerged about Barney being a pupil of Angelica Kauffman.

But it is worth mentioning that in the correspondence between Barney

and Soho factory the names of Kauffman's characters 'Trenmore' and 'Imbaca'

are constantly misspelled. This fact indicates Barney's

unfamiliarity with James Macpherson's 'Ossian', and also raises

additional doubts in his close contact with Angelica Kauffman in

1770s, as she painted her painting when Barney was supposedly her

pupil, and if so, he should have been familiar with it. |

Original for a mechanical painting

finished by J. Barney:

Benjamin West. The Cave of Despair, 1776.

©Yale Center for British Art. Paul Mellon Collection. |

In Barney's correspondence there are references to a few additional

paintings which were not mentioned in either Inventory: 'The Cave of

Despair' and 'Daniel Interpreting the Writing on the Wall' after

Benjamin West, 'Patience' and 'Perseverance'

after

Angelica Kauffman, the 'Good Shepard' (the artist not mentioned),

two circular paintings 'Cupid Triumphant' and 'Graces breaking

Cupid's bow' (also after Angelica Kauffman), and four bas-reliefs

with unidentified subjects.[19]

|

|

The work on mechanical paintings was a slow and difficult process.

Working on Matthew Boulton's personal order, Barney did not succeed

with 'Antiochus and Stratonice' and wrote on the 17th May 1781:

'I

am sorry I have not succeeded in my endeavours to please Mr Boulton

on the last picture. /…/ I certainly shall feel sensibly the having

such picture as Stratonice returned upon my hands but if Mr Boulton

chooses to send me over the printed impression I will make as good a

picture of it as I probably can. /…/'

[20] |

|

Original for

a mechanical painting finished by J Barney

Benjamin West. Daniel Interpreting

Scriptures on the Wall. 1775. ©Berkshire

Museum, Pittsburg, MA. |

|

| When a month later it still

was not good, Barney wrote on 29th of June: 'I should take it as a

favour if you will please to forward one of the pictures of Stratonice which I am to paint for Mr Boulton as I purpose being in

London in about a fortnight[21] and taking the picture in order to

finish it from the original at Mr West's.'

[22] All paintings associated with Joseph Barney from the Soho period, be

it mechanical or original, are figurative. His fondness of Benjamin

West's works is particularly evident. Many of them, along with

large-scale paintings by Angelica Kauffman, are complex

many-figures compositions. Touching and painting their mechanically

reproduced copies invariably employed the close observation of their

technique, colours, and artist's style and manner. However

slave-like and ungrateful Barney's work was, it provided a great

deal of training and artistic practice. Barney's abilities in

figurative painting were appreciated at Soho. At least three other

artists were employed for finishing mechanical paintings - Mr

Richard Wilson, Mr Simmons, and Mr Parsons - but Joseph Barney was

considered the best by his Soho employers. When in 1780 an impatient

customer wanted to purchase mechanical paintings which were not in

the sale room, and did not want to wait, he was offered mechanical

paintings which were in the possession of Matthew Boulton himself on

the understanding that they can be easily substituted by a skilful

artist and even be of a better quality.

Hodges wrote to Matthew

Boulton: 'R Barwell, Esq. of Ormond Street, London, visited Soho and

ordered upwards of £85 worth of pictures. He chose them chiefly from

those at your house, and as he wanted them sooner than in was

possible to get them up, (by Mrs Boulton permission) we purpose

taking two pieces out of your room, ie the Physician Erasistratus

and the large Good Sheperd, which pieces I learn may be substituted

by Mr Barney better than those…'

[23] In 1781, Isaac Hawkins Browne

(1745-1818), refurbishing his home at Badger Hall, desired to

decorate it with mechanical paintings. Boulton and Fothergill,

however, were ceasing the production, but they referred him to

Barney, obviously giving him the best recommendations. Expressing

his disappointment, Browne wrote back: 'I am obliged to you for your

recommendation of Mr Barney. I shall certainly pay attention to his

extraordinary merit.'

[24]

Who bought mechanical paintings finished by Joseph Barney?

Modern researchers have noticed that Josiah Wedgwood, surprisingly,

used very few of Angelica Kauffman's works in his classical designs

for jasper ware. But at least he did acquire mechanical paintings

after Kauffman's designs: Barney's Graces breaking Cupid's bow and

Cupid struggling to recover his arrows were made for Josiah

Wedgwood.[25] Along with Wedgwood and Boulton, Barney's other customers

were Mrs Elizabeth Montague (1720-1800), Sir Sampson Gideon

(1744-1824)[26], and, possibly, Beilby Porteus, the Bishop of Chester

and a well-known abolitionist (1731 - 1809)[27], Lord Macclesfield[28] and

Isaac Hawkins Browne, if he followed Boulton's recommendation.[29]

Joseph Barney's own paintings

Working for Soho, he at the same time painted his 'Deposition from

the Cross' for St John's church, Wolverhampton. Hundred years later,

referring to the account of the painter and engraver John Whessel

(1760-1824) who had lived in Wolverhampton in the 1780s and known

Barney, James P. Jones wrote that Barney had painted each figure

from life, and while having difficulties with the image of Joseph of

Arimathea, he 'saw a very indigent man on the street, whose face

just met his idea. He invited him to his studio and sketched him

onto canvas.' [30] In some indirect way, this again confirms Barney's

familiarity with portrait painting. One of his letters to Soho

reveals a touching detail of this work: 'I write this in bed having

had the misfortune to fall as I was painting at the Altar piece by

which I have totally lamed myself for some weeks…'

[31]

In 1784, Barney still was in the Midlands, painting his second altar

piece, 'The Apparition of Our Lord to St Thomas' for St Peter & St

Paul's Roman Catholic church, and exhibiting at the Royal Academy

from Summer Hill, Birmingham.

It also seems that he painted other, his own, pictures, and possibly

was allowed to sell them from the Soho showroom. On 12th June 1781

he wrote to Soho: 'Please to let the large picture stand in the Toy

Room until I see you. There is a large picture of mine in the Toy

Room where I used to paint. It is a big picture of Eneas.'

[32] There is

no record of any mechanical painting with a subject from the

Virgil's 'Aeneid' in the Soho Inventories, thus it is possible that

it was Barney's original painting. In May 1782, when the production

of mechanical paintings at Soho ceased, and Barney's collaboration

with Soho ended, he wrote: 'I have sent two pictures by the bearer viz:

Time and Cupid and Cupid bound to a tree. I have

likewise sent every thing I had in possession belonging

to Soho. /…/ If you have any other command please to

send them by the bearer to whom I should be glad you

will deliver my picture of the Forge.'

[33] Although one of

mechanical pictures represented 'The Forge' after Wright of Derby,

it is possible to suppose that in this particular case he also

mentioned an original painting by himself which may or may not have

been inspired by Wright of Derby.

Joseph Barney's japanned ware

Considering rather inadequate payment offered by Soho, it is clear

that Barney desperately needed another source of income, and it is

very likely that he decorated his father's japanned ware, although

not formally joining the business. In 1883, George Wallis wrote:

'Joseph Barney /…/ painted trays for a japanning concern in the town

of which his father was proprietor.'

[34] |

Japanned tray ‘Jerusalem Hath Sinned’. J Sankey & Co.

Bilston, mid-19th C. |

Unfortunately, japanned ware

are mainly anonymous, thus their identification and attribution is

very difficult and often muddled: In 1950, Bernard Hughes

confidently attributed to Barney a magnificent round

japanned tray painted with a 'scriptural' scene, which

at that point the author had seen in the collection of

Wolverhampton Art Gallery.[35]

In 1964, reproducing this tray in their book 'English Decorated

Trays', John and Jacqueline Simcox named the scene 'Jerusalem Hath

Sinned', and repeated the attribution to Joseph Barney and to the

firm of Bevins & Barney.[36] But at the same time, they dated the object

'c.1835-1845' which contradicts with the artist's life dates.

In fact, this tray had been loaned to the Gallery by Mrs G.Sankey-

the fact which immediately challenges the attribution to the Bevins

& Barney business. |

| On the lists of material on loan for the insurance

purposes, which were compiled by the Gallery in 1974 and

1977, it has the same attribution to Joseph Barney, but

the obvious discrepancy in dates was corrected to

'early 19th century'.

[37]

In 1982, in the Catalogue of Georgian and

Victorian Japanned Ware published by Wolverhampton

Art Gallery, the name of the painter disappeared, and

the tray was described as made by J. Sankey & Co, Bilston in the

mid-19th century[38]. The tray does not bear any stamp of Sankey

& Co. The original source of its decoration was not

established. It might have been an engraving by John

Rogers (c.1808-1888) which is dated 'c.1860'.[39] |

John Rogers (c.1808-1888). ‘Jerusalem Hath Sinned’.

1860s. |

Japanned tray ‘Finding of Moses’. Joseph Sankey &

Sons Ltd, Bilston, mid-19th C. |

WD John and Jacqueline Simcox also ascribed to Joseph Barney a large

tray painted with the 'Finding of Moses'. This tray is

well known in Wolverhampton.

Its origin at Joseph Sankey & Sons Ltd,

Bilston has been firmly established, although its date is doubtful.

According to Wolverhampton local information, it was made for the

Great Exhibition of 1851. But in fact, Joseph Sankey was born in

1827 and started his business in the middle of the 1850s, several

years after the Great Exhibition.

Thus if the origin and dates of

both trays are correct, they cannot be attributed to Joseph Barney[40].

In fact, with the absence of documentary evidence any attribution is

highly speculative.

|

| Barney's correspondence with Soho confirms that he often borrowed

prints and engravings from Matthew Boulton's house, particularly

those after Benjamin West and Angelica Kauffman, for working on

mechanical paintings, but also probably for decorating the japanned

ware. In June 1781, he wrote: 'General Wolfe and Daniel

Interpreting the Writing on the Wall belong to Mr

Boulton. /…/ Mr Boulton has a print of the Cave of

Despair which I hope he will lend me for a short time'

[41]

George Wallis remarked: 'I have myself seen trays

attributed to Angelica Kauffman, being from the

subjects which I had no doubts were really painted by

Barney.' [42] |

| In Wolverhampton context, Barney's work on a large mechanical

painting after 'The Death of General Wolfe' by Benjamin West[43] is of

particular interest - in 1972, Wolverhampton Art Gallery acquired a

japanned tin serving tray painted with this scene.[44] John

and Jaqueline Simcox reproduced a similar tin tray from an American

private collection, painted with the same subject but of a different

shape, and dated it 'c.1800.'

[45]

Wolverhampton tray was described in 1982 Catalogue as

'English or Welsh' and dated 'c.1795', which was

probably based on J and J Simcox' book.[46] |

Japanned tray painted with ‘Death of General Wolfe’

after B. West.© WAG. |

Considering the presence of the engraving and the mechanical

impression of the West's painting at Barney's home in 1781, it is

possible to date these tin trays 'c.1780s', and if not to attribute

to, but at least to associate it with Joseph Barney himself, or with

Barney & Ryton (although again all attributions remain highly

speculative).

In July 1800, Barney paid a brief visit to the Midlands, and called

at Soho to borrow a picture on which he had worked long ago: Sir, it

is so long since I had the pleasure at assisting you that I may

probably be erased from your recollection, indeed it is necessary to

apologise for troubling you on the present occasion which is to

request that you will have the goodness to lend me the small picture

of the Good Shepard in order that I may make a sketch from it whilst

I remain in this part of the country. Your consent signified in any

way you think proper to Mr Eginton will greatly oblige.[47]

This desire

to borrow a picture also can be understood as a need to have some

original for a decoration of a japanned tray. However, it is hardly

possible to confidently attribute any unsigned japanned object to

Joseph Barney without any firm documentary evidence.

At the cross-roadsThe production of mechanical paintings was a rather short-lived

enterprise. In May 1782, Barney's collaboration with Soho ended, and

finding another position which would satisfy his goals and ambitions

appeared not easy. Between 1786 and 1793, we see him in London, at

29, Tottenham Street, actively exhibiting figurative and historic

paintings at the Royal Academy. The London Book Trade names him as

an engraver and print-seller.[48] His

'Scene in the 'Tempest'' exhibited

in 1788 might indicate his ambition to join the Boydell's

Shakespeare Project in which his friends Benjamin West and Angelica

Kauffman participated.

Drawing Master

In October 1793 Barney took the post of the Second Drawing Master

for Figures at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich (which again

contradicts with his characteristic as 'fruit and flower' painter)

and moved to Greenwich. There he remained until 1820.[49] |

|

Joseph Barney

after F.Wheatley. Fisherman’s Return. 1793. |

|

The role of Drawing Master for Figures obviously influenced Barney's

later subjects, increasingly sentimental, of lesser artistic quality

then his earlier works, but still figurative, not 'fruit and

flowers'. They reveal his close collaboration with Francis Wheatley

(1747-1801), Charles Turner (1774-1857), William Hamilton

(1751-1801), Thomas Gaugain (1756-1812).

In July 1811, the 'Wolverhampton Chronicle' proudly

announced that 'Mr Joseph Barney, Professor of Figure

and Perspective Drawing to the Royal Military Academy at

Woolwich, is appointed Painter in Flowers and Fruit to

His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales. Mr Barney is a

native of this town and it gives as a pleasure to learn

that His Royal Highness the Prince Regent, whose taste

for the Fine Art is so universally acknowledged, has

honoured him with so distinguished mark of his

appreciation.'

[50] |

| This title confirmed his

artistic efforts, but hardly recognised his lifelong artistic

ambitions: even as 'Painter on Flowers and Fruit' he did not

increase a number of exhibited still-life pieces and continued

presenting himself as a historical artist, exhibiting his early

works - the 'Lame Man healed by St Peter and St John' was exhibited

in 1786, 1802, and 1814; the 'Manoah Sacrifice' - in 1798, 1819, and

1820. 'Belisarius' was shown five times: in 1784, 1806,

1809, 1821, and 1822.

The titles of some other exhibited artworks correspond

with paintings by Antonio Zucchi and Benjamin West, with which he

worked producing mechanical paintings: the 'Wise Men's Offering' was

shown in 1818 and 1820, the 'Daniel Explaining to Belshazzar the

Writing on the Wall' - in 1824 and 1827. The title of the painting

exhibited in 1822 at the Royal Academy, 'The Graces Adorning the

Bust of Princess Charlotte', suspiciously reminds about Angelica

Kauffman's 1770s works.

It is impossible to believe that Barney

exhibited some surplus of mechanical paintings as his own original

works, thus these were probably versions, or inspired by the same

subjects. |

|

Thomas Gaugain after

Joseph Barney. The Show Man (La Pièce

Curieuse). 1802.

|

|

|

Joseph Barney. The Thatcher. 1802. |

G. B. Hughes wrote in 1950 that towards the end of his life, Barney

had returned to Wolverhampton, and painted japanned trays for his

brother, partner in Bevan & Barney.

This information has not been

confirmed by other sources: Graves' Dictionaries show that even

having retired from the Woolwich Military Academy, Barney continued

exhibiting from London addresses, although indeed he often visited

his relatives in Wolverhampton. |

| The family The current entry for Joseph Barney in the DNB does not provide full

information about his family. Wolverhampton sources mention the

daughter Jane Whiston, born in October 1780.[51] A son Joseph, the

future artist, was born in April 1783.[52] He started to exhibit in

1817 from his father's address in Greenwich; in 1818 he moved to 17,

Great Smith Street, Westminster, and finally to Southampton, from

where he exhibited until 1842.

He was a drawing teacher[53],

exclusively a fruit and flower artist, and in the late 1830s became

a Fruit and Flower Painter to Queen Victoria. Another Barney's son

was a promising printmaker and publisher William Whiston Barney, a

pupil of S.W.Reynolds.

He, however, abandoned his artistic career,

joined the army, and distinguished himself in the Peninsular War[54].

According to Australian sources, a third son, George (1792-1862)

born in Wolverhampton[55], became a soldier and military engineer who

also served in the Peninsular War and in the West Indies, and later

took a significant place in the history of Australia[56]. In May 1793,

a daughter Sophia was born in Greenwich[57], in 1796 - a son John

Edward[58], and in 1799 - a daughter Ellen[59].

The fact that in the family there were three artists with the same

name - Joseph Barney Senior (Wolverhampton Japanner), Joseph Barney

Junior (artist and pupil of Zucchi) and Joseph Barney- Fruit and

Flower Painter to Queen Victoria - who worked in similar style,

definitely caused confusion between them.

In 1997, Keith Jobst, an Australian and a distant descendant of

Joseph Barney, published in Brisbane a book 'The Barneys'.

1835-1865'. It is mainly dedicated to Barney's children and

grandchildren, but the first chapter gives an overview of the

artist's life and work. Unfortunately it is mainly based on already

known sources. On 25th March 2004, the Wolverhampton newspaper 'The

Black Country Bugle' published a large article 'The Wolverhampton

Painter of the Black Country's own 'Passion of the Christ'

- and his

Illustrious Ancestors'[60]. The author in a rather unfortunate way

tried to establish links between Joseph Barney and Mel Gibson's film

'Passions of Christ' which was released at that time. The article is

partly based on already known sources, including Keith Jobst's book,

but at the same time it ignores important facets of Barney's life

and work. The absence of references makes the article unreliable.

|

The conclusion: artistic legacyThe conclusion is that, unfortunately, Joseph Barney did not manage

to fulfil his artistic ambitions and establish himself as a historic

painter. His name is associated today with short-lived enterprise of

mechanical paintings, obscure 'fruit and flowers', and cheap

sentimental colour prints, if not practically forgotten. The

location of his large-scale historic and religious paintings is

unknown. Maybe this is the time to start looking for his artistic

legacy, and to remind about respect which his contemporaries paid to

him. Reporting Barney's death in April 1832, The Staffordshire

Advertiser wrote: 'On the 13th inst., at his house,

Stanhope-Terrace, Regent's Park, London, Joseph Barney, Esq. [died],

aged 77. He was an eminent painter, and for more than 30 years

drawing master at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. The altar

pieces at St John's Church and at the Catholic Chapel, in

Wolverhampton, of which he was native, formed lasting monuments of

his skill as an artist.'

[61]

|

|

References:

[1] Shaw, Stebbing. History of

Staffordshire. Vol.2, part.1. 1798. P.164.

[2] Late 18th century trade directories of

Wolverhampton and Staffordshire record the presence in

Wolverhampton of several entrepreneurs named Barney, who

may or may not be members of the same family:

In 1770, three businesses of Barneys were recorded in

Wolverhampton:

1. Joseph Barney, corn factor and mealman. He lived in

Lichfield Street in 1767-84.

2. Benjamin Barney, smooth file maker, was in Stafford

Street.

3. Barney & Ryton, japanners, coffin plate chasers and

merchants, also were situated in Stafford Street.

In 1780, several additional businesses were recorded:

4. James Barney, ironmonger and locksmith, in Dudley

Street;

5. Mrs Barney, a milliner, in Church Yard;

6. Joseph Barney, ‘unqualified painter’, who had his

lodgings in Horse Fair between 1780 and 1782.[1]

The 1783 Directory mentions only Barney & Ryton,

japanners, in Stafford Street, and Joseph Barney, a corn

factor. In 1792, Benjamin Barney, a file maker, still

continued his business. Joseph Barney-japanner moved to

the Queen Street. In 48, Dudley Street appeared inn

keepers Elizabeth Barney, widow, and Eleanor Barney. At

50, Horse Fair, John Barney, jeweller, has been

recorded. In 1802, Joseph Barney in 5, Queen Street was

listed among tinplate workers (makers of blank trays).

Barney & Bevins continued their japanned ware business

in Goat Street.

An additional document is

preserved in Birmingham Diocesan Archives: Indenture of

a lease of a dwelling house in Stafford Street by Joseph

Barney, Japanner, from Benjamin Barney, file maker, for

one year, signed on 6th January 1788. It helps to

identify Joseph Barney Senior, the father of the artist,

as a japanner in Stafford Street and a partner of Barney

& Ryton between 1780-1802. The ‘unqualified painter’ who

lodged in 1780-82 in Horse Fair is his son, the artist

Joseph Barney Junior. The fact that at his native town

he was at that time considered ‘junior’ is confirmed by

documents related to the commission of the painting for

St John’s: ‘to article with Mr Jos.Barney Jun’r to

paint and complete’ the altarpiece’. Local documents

help to recognise James Barney-ironmonger as a brother

of the artist. He seems to abandon his ironmonging trade

and became a keeper of the ‘Castle Inn’. Thus he does

not seem to have had artistic training. He died between

1785-1792, thus his business was continued by his widow

and daughter, and finally sold in 1811. Barney the

partner of Bevins in 1802 may indeed be another brother

of Joseph Barney Junior (as mentioned in Cleevely’s

entry for DNB, 2008), but his given name was not found

in the local historic listings.

[3] The date of Joseph Barney’s birth has

not been established for sure, as the baptism records of

Wolverhampton St Peter’s church do not contain the

record for Joseph Barney. R. J. Cleevely, the compiler

of the current (2004-2008) extensive entry for Barney in

DNB provides the date of his birth as 4th March 1753,

but without reference to the source of this information.

This nevertheless seems plausible, as the marriage of

his parents, Joseph Barney (Senior) and Eleanor Denham,

was recorded at Wolverhampton St Peter’s church on the

30th November 1751.

[4] Wood, Henry Trueman. A History of the

Royal Society of Arts. 1913. P.164

[5] Wolverhampton Local Archives,

DX-174/7.

[6] Wolverhampton Public Library and Art

Gallery Minutes Book 6. CMB/WOL/AGPL/5.

[7] Hughes, G Bernard. Wolverhampton

Decorated Trays. In: Staffordshire Life and County

Pictorial. 1950, Vol.3, No5.

[8]

www.invaluable.com. 2003, Lot 507.Last access

16.03.2009.

[9]

www.invaluable.com. 2003. Lot 508. Last access

16.03.2009.

[10]

R. J. Cleevely,

‘Barney, Joseph (1753–1829?)’, Oxford Dictionary of

National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004;

online edn, Jan 2008.

http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/1486.

Last access 5 April 2009.

[11] Ibid.

[12] In Keith Jobst’s book ‘The Barneys.

1835-1865. Brisbane, 1997’she is called ‘nee

Chandler’. P.86 ea.

[13] Eric Robinson and Keith R. Thompson.

Matthew Boulton's Mechanical Paintings. The

Burlington Magazine, Vol. 112, No. 809, pp. 497-507.

[14] Joseph Barney ‘consented to work

by the day to retouch the boys’ pictures, at 10/6 a day.

If the painting business is to be carried on, and the

boys continue to paint, certainly the value of the

pictures will be enhanced more that the

expense

of his wages.’ J Keir to MB. 2.12.1779.

MS3782/12/65/43.

[15] MS3782/12/65/43. Keir to MB.

2.12.1779.

[16] In 1970 at Birmingham Assay Office;

now Birmingham City Archives, MS3782/1/31/1-16.

[17] MS3782/1/30. B & F to Clarke & Green,

10.07.1781. Letter book 1777-1782. B&F to Baron de

Watteville de Nidan, 23.12.1780; The Mint Inventory

1809.

[18] According to published information, a

painting by Angelica Kauffman has been preserved at Browsholme Hall, Lancashire (http://www.browsholme.co.uk).

It is worth checking whether this is a mechanical

painting.

[19]

www.invaluable.com. Last access 16.03.2009.

[20]MS3782/1/32/1-16

[21] Barney’s trip to London may have been

related to his Golden Palette awarded by the Society of

Arts, but its timing also suspiciously coincides with

the wedding of Antonio Zucchi and Angelica Kauffman

which took place on the 14th July 1781, thus

he might have attended the event.

[22] MS3782/1/32/1-16

[23] MS3782/12/63/19. 31st

October 1780.

[24] MS3782/12/27. 8th

September 1781.

[25]MS3782/1/32/1-16. 8th

January 1782. Bill.

[26] MS3782/12/63/12. 17th

April 1780.

[27] MS3782/1/30. July 1781: ‘…Penelope

and Calypso… to be sent to his Lordship House in Great

George Street, Westminster.’

[28] MS3782/12/63/13. 1st May

1780: ‘The Calypso you ordered for Lord Macclesfield

was sent the 27th ultimo to care of Mr

Stuart…’

[29] Badger Hall was demolished in 1952,

and its ceiling paintings were installed in the house of

Buscot Park, Berkshire. While their classical manner is

indeed in the manner of Angelica Kauffman, their

subjects differ from these which were mechanically

reproduced at Soho in the 1780s, and which were finished

by Joseph Barney. Also, there is no evidence of their

‘mechanical’ nature.

[30]Wolverhampton Local Archives,

DX-174/7.

[31] MS3782/1/32/1-16. 15th May

1781.

[32] MS3782/1/32/1-16. 12th

June 1781.

[33] MS3782/1/32/1-16. May 1782.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Hughes, G Bernard. Wolverhampton

Decorated Trays. In: Staffordshire Life and County

Pictorial. 1950, Vol.3, No6.

[36]W D John and Jacqueline Simcox.

English Decorated Trays (1550-1850). The Ceramic Book

Company, Newport, England, 1964. P.116-117.

[37] Materials on donors. File ‘Sir

Edward Thompson’. Wolverhampton Art Gallery.

[38]Jones, Yvonne. ‘Georgian and Victorian

Japanned Wares of the Midlands. Catalogue of the

permanent collection and a temporary exhibition.’ 1982.

P.85.

[39]

www.old-print.net.

Last access 18.07.2009.

[40] The catalogue of Wolverhampton Local

Archives provides the information that it was painted by

John Barney, a Bilston artist employed at the J Sankey &

Co. The name John might be a writing error, but if so,

there is still a discrepancy between the supposed date

of the tray and dates of Joseph Barney’s life, and there

is no evidence of him being employed by J Sankey. If

the name of John Barney is correct, we do not know

whether he was a member of the family.

[41] MS3782/1/32/1-16. 12th

June 1781.

[42] Wolverhampton Local Archives,

DX-174/7.

[43] ‘Barney sent from Wolverhampton

large picture of General Wolfe…’Hodges to MB.

30.11.1781. MS3782/12/63/20.

[44] WAG, LP311

[45] W D John and Jacqueline Simcox.

English Decorated Trays (1550-1850). The Ceramic Book

Company, Newport, England, 1964. P.120-121.

[46] Jones, Yvonne. Georgian and Victorian

Japanned Wares of the Midlands. Catalogue of the

permanent collection and a temporary exhibition. 1982.

P.74-75. In an informal discussion, Yvonne Jones agreed

with a possibility of this attribution.

[47] MS3782/12/45/200. 2nd

July.1800.

[48] Exeter Working Papers in British Book

Trade History. The London book trades 1775-1800: a

preliminary checklist of members. Names B.

http://bookhistory.blogspot.com/2007/01/london-1775-1800-b.html.

Last access 6 April 2009.

[49]

Email from Dr A R Morton,

Archivist/Deputy Curator, Sandhurst Collection RMAS:

Cattermole F J. Records of the Royal Military Academy

1741-1892. Woolwich, 1892.

[50] Wolverhampton Chronicle. 10 July

1811; Graves, A. The British Institution, 1806-1867.

1875. P.29.

[51] Wolverhampton St Peter: Baptisms

1539-1812. Surname ‘Ba’.

http://www.gpt63.dial.pipex.com/stpeter/bap-b-ba.pdf

[52] Ibid.

[53] Pigot’s Directory, 1830.

[54]Knoedler & Co. Biographical notes of

XVIII & XIX century mezzo-tinters not mentioned in our

two previous brochures.1905. P.27.

[55] In Wolverhampton sources, there is no

record of George Barney’s birth or baptism. Also, it

seems that the family lived in London at that time.

[56]

Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume

1, 1966, pp 60-61. Sutton R. George Barney (1792-1862),

First Colonial Engineer.// Engineering Conference 1984:

Conference Papers. Institution of Engineers, Australia.

No84/1. Pp.13-17.

[57] International Genealogical Index:

http://www.familysearch.org/Eng/default.asp

[58] International Genealogical Index:

http://www.familysearch.org/Eng/default.asp

[59] International Genealogical Index:

http://www.familysearch.org/Eng/default.asp

[60] No author. The Wolverhampton

Painter of the Black Country’s own ‘Passion of the

Christ’ – and his Illustrious Ancestors.’// The

Black Country Bugle. 25th March 2004.

[61] Cit. in: Jobst, Keith. The Barneys.

1835-1865. Brisbane, 1997. P.3. |

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|