BILSTON AFTER THE NORMAN CONQUEST

This page is decorated with line drawings taken

from medieval manuscripts. They have no specific connection

with Bilston but do represent typical scenes from the times.

The chief, if not the only,

effect that the Norman conquest had on Bilston was that one set of

landowners was replaced by another. For the inhabitants the round

of agriculture would have gone on as before.

Lawley gives the following

translations of the local entries in Domesday Book:

In Bilston there are two

hides of land, which is four caracates, and there are eight

villeins and three boarderers with three ploughs. Also one acre

of meadowland. The wood is about a furlong long and a half

broad. Was worth 20s, now 30s.

Walbertus holds of

Williams (Fitz Ansculf) one hide in Bradley. There are 2

caracates, with them are 4 villiens having one plough. The wood

is 3 furlongs long and one furlong broad. Valued and now of the

value of 67 pence. Untan holds by sac and soc. There are two

acres of meadowland.

|

St. Leonard's in modern times. |

The figures indicate that

Bilston was, by the standards of its time, a sizeable village and

that Bradley might be described as less developed, having more

woodland and fewer inhabitants.

There is no mention in Domesday

Book of a church in either Bilston or Bradley and this

is certainly because the church at Wolverhampton was the

local parish church.

Lawley insists that

there was a church of some sort in Bilston from the earliest

Christian times and that references in old deeds to Wolverhampton

church and its chapelries show that there must have been a chapel,

at least, in Bilston. It is possible; but it is more likely that

St. Leonard’s found its origins at the end of the 11th

century, when there was a spate of church building throughout the

country. |

It seems that after 1066

Wolverhampton and its surrounds came to be in only two manors, the

Deanery Manor and the Stow Heath Manor. Stow Heath spread from the

centre of Wolverhampton to the east and Bilston itself was in it.

Bradley was not – it was in its own Manor of Bradley. Of Stow Heath

manor Chris Upton (in his “A History of Wolverhampton”, (1998)) says

that “Stowheath represented, in fact, a merger of the royal manors

of Bilston, Willenhall and one half of Wolverhampton, a process only

completed in the 13th century. The first lord of the

manor was Robert Burnell, Bishop of Bath and Wells and Chancellor of

England until his death in 1292. His main dwelling was … at Acton

Burnell”.

| The descent of the ownership

of the manors of Stow Heath and Bradley can, to a large extent, be

traced – and the details are in Lawley. Suffice it to say here that

Stow Heath Manor came into the hands of Bilston based people and

seems to have been run from the house which is now the Greyhound and

Punchbowl. Where the manor of Bradley was run from is not known.

The main function of a manor was to regulate the course of

agriculture in its area, though it exercised rather wider influence

over its inhabitants than that might suggest, not least because, in

early post-conquest times, there was not the same distinction

between criminal and civil matters as we would make today.

|

The Greyhound and

Punchbowl in modern times. |

A royal hunt in a royal forest

such as Cannock Chase or Kinver Forest. Bradley

seems to have been a hunting ground, but not a royal

one. |

In addition to the manorial

courts, the area would have been run by various royal officers in

various guises, most of whom would, in due course, have been

replaced by magistrates (or Justices of the Peace) sitting in petty

sessions and quarter sessions, at both of which minor criminal

matters would have been dealt with, alongside some civil matters.

There would also have been a hundred court – and Bilston was in Offlow Hundred – and a county court. These courts would have dealt

mainly with what we would see as civil matters. Doubtless

Bilstonians attended all these courts but their impact, other than

that of the manorial courts, on their daily lives would have been

small. |

| In medieval times we must

imagine Bilston as a village, surrounded by open fields and some

meadowland, and, beyond them, woodland areas on all sides, with the

extensive royal forests beyond them to the north and to the west.

The village’s principal roads would have been much as they are now

with the exception of Wellington Road and Oxford Street, both of

which were not to appear until the 19th century.

|

Ladies hunting. In medieval times women could be strong and independant

figures. |

|

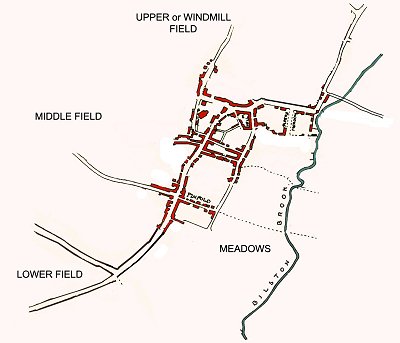

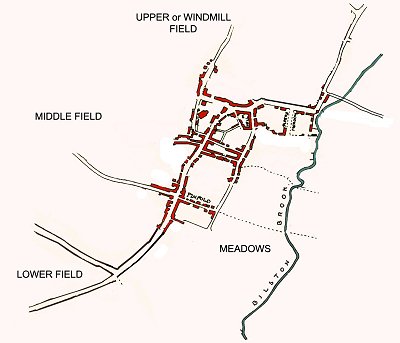

A rough guess at how Bilston

would have been in the later medieval period, with three

open fields around a village centred on the church; and

meadow lands between the village and the brook. (Based

on an adaptation of the 1832 map of Bilston).

|

Water would have come from wells and, at

a little distance, from the brook. The chief well was known as

Crudely or Cruddley Well and was situated, Lawley says, “just off

Lichfield Street, near to the entrance to Proud’s Lane”. There was

another well at Spring Vale, known as Lady Wulfruna’s Well. Both of

these wells were considered, from time to time, to be Holy Wells

with curative properties.

| The village would have been

not unlike that shown on the 1832 map of the town –

basically a village spread along a single street

with a few branches off it developing over a period

of time. The housing would have consisted of

an accumulation of cottages – mere hovels to our

eyes – and a wider scattering of the better houses

of the better off landowners. These houses

would have been “half timbered” on brick, or

possibly stone, bases. |

A medieval

house of a good class. |

Medieval timber framing, still

around at the start of the 20th century. Thanks to

Eric Woolley for this. |

The single street layout

would have been broken around the chapel, as it is today. A chapel

is known to have existed on the site of St. Leonard’s, in 1090, when

the priest was one Robert Fitzstephen.

Lawley describes this as a

free chapel, one not allocated to any of the prebends of St.

Peter’s. But a chapel it was and a chapel of ease

– that is an ecclesiastical building, with a curate (not

a vicar or rector), which was provided for the

convenience of people living at some distance from their

parish church, in this case, St. Peter’s.

|

In theory the curate would

be appointed by the mother church; but the practice later developed

of the curate being elected by the townspeople. A chapel of ease

could not perform christenings, churching of women, marriages or

burials. How it came about that, eventually, all of this

ceased to apply to St. Leonard’s, even before it became an

independent church, can be read elsewhere.

| Beyond the village, presumably

near the brook, was some meadowland, which would have

been used for making hay and grazing cattle.

The

back yards of the cottages would have been used for

growing vegetables and keeping pigs and the pigs would

have foraged the surrounding woodlands. |

Reaping the

lord's land under his steward. |

|

Netting birds. |

The

main agricultural activity of crop farming would have been carried

out in Bilston, as it was almost everywhere else in the Midlands, in

open fields. These were very large fields which were divided into

strips (usually about a furlong long and about 20 feet wide) and the

villagers would each have held an allocation of strips scattered

around each of the open fields. |

| Bilston had a market, almost

certainly on the site where it still is; although the date of its

origin is uncertain, Lawley says that a market charter was granted

by Edward III. At some date a “market cross” was

erected. A market cross was, originally, just

that: a large cross, on a plinth, which marked the

centre of the market and around which local people came

to sell their goods to other locals and visitors.

Later the cross itself might have been replaced by a

building, usually in the form of an open area at ground

level, with an upper floor supported on pillars. |

Milking cows and

churning butter. |

A tapster. It is reasonable

to assume that Bilston would have acquired some beer

houses and an inn or two. |

Bilston seems to have had two crosses: the Nether Cross

and the Overas Cross. The Overas Cross was taken down in 1698 and

the materials used to rebuild the Nether Cross. As was common with

such buildings the open area beneath the Overas Cross was bricked in

to form a ground floor room. In 1738 it was leased to a private

individual and thereafter disappears from the records.

Open field systems of

agriculture usually had three open fields, but variations on this,

from two to five fields, are not unknown. We do not know for

certain how many open fields Bilston had but it seems, from the

names occurring at various points in Lawley’s History, that there

were three: Upper or Windmill Field; Middle

Field; and Cole Pit Field. |

| One would guess that Middle Field was to the west of the

village (where Middle Field Lane ran); that Upper Field was to the

north and west, it being described in 1458 as lying “near the way

from the said Bilston to Wolverhampton”; and that Lower Field was to

the south, the eastern side being occupied by the meadow near the

brook. It was the chief business of the manorial court to decide on

the course of agriculture – what was grown in each field; when

ploughing, sowing and reaping took place and when, after harvest,

the fields were to be thrown open to all villagers for grazing. The

notes made by the Reverend Ames show that this system of agriculture

was still operating, over a greater or less area, in his time.

The name “Windmill Field”

indicates that there was a windmill but windmills did not appear in

England before the 13th century; before that corn

was probably ground at a mill powered by the brook.

Certainly there was a water mill, as one is mentioned in

a deed of 1378 cited by John Price. |

Bilston windmill

- a post-medieval construction. Thanks to Reg

Aston for this. |

How land in Bradley was laid

out and used is even more obscure. Lawley suggests that the area

was used mainly as part of the Earls of Dudley’s hunting grounds;

and he finds only five capital messuages there (that is, five houses

of any size). There is a reference, in 1378, to Boverbrook Field

and a reference to Broad Meadow in 1459 and this may show that there

were open fields and a meadow in that manor as in Bilston. The

names of some landowners are known and appear in Lawley, as do the

names of many more in Bilston itself.

Pipe Hall, named after a local

landowning family; but this was built long after the

Pipes had left the area. |

These landowners were all people

who, by hard work, wheeling and dealing, or just good

fortune, accumulated much of the land into their own

hands and built the larger houses in the village.

They were also, as like as not, the leaders in

“enclosing” the open fields.

Enclosure was the

process by which the old strip farming was abandoned,

scattered strips were brought together and enclosed in

fields of the shape and size with which we are now

familiar. This was often done in one fell swoop under

the compulsion of an Act of Parliament; but there

is no Act covering Bilston or Bradley. |

| So there must have been what

is known as “enclosure by agreement” whereby, possibly over a

prolonged period, maybe decades or even longer, swaps and purchases

of strips were agreed between their respective owners until everyone

had his land in consolidated areas like modern fields.

The written

record reflects this process. In Bradley a deed (said to be of 1479

but strangely worded for that date) mentions an area of land “taken

and enclosed before Queen Mary’s time” and that before it was

enclosed it was called Broad Meadow. This is not entirely clear but

the early date (if accurate) suggests that this enclosure was

carried out by a landowner for the purposes of producing a sheep

run. If this is the case the deed also reflects the undoubted

importance of sheep farming to the area. |

A medieval town. |

|

Cooking for a feast. |

Land in a manor’s open fields was

(certainly for the greatest part) not freehold but

copyhold. Copyhold tenure depended on registering

one’s title, and all dealings in the land, with the

manorial court. As land was enclosed the manorial

court no longer needed to meet to regulate the course of

agriculture and, very often, manorial courts fell into

decay. This meant that land transactions in

copyhold land became difficult and uncertain.

|

| It may be that this happened in

the whole of the Black Country area, with prime land

within and immediately around the villages becoming

enfranchised as freehold land, and the rest remaining

copyhold. It is possible that much mining and

other industrial development could take place between

the villages because it became uncertain who owned the

land or had any form of control over it. |

A stag hunt.

This sport would have been the preserve of the nobility. |

|

A cloth merchant. |

Dr. Rowlands finds, in most of the Black Country, a

relatively strong manorial system in which the custom of some manors

gave underlying minerals to the copyholder and some to the lord of

the manor. Which category the Bilston manors fell into is not

clear.

But, one way or another, through the manorial courts or

through encroachment, there seems to have been no legal problem in

exploiting the mineral wealth beneath Bilston. This aspect of the

development of industry in the area merits further investigation. |

Most of the Bilston

landowning families remained in the area or thereabouts. Only a few

appear on the national scene. For example, the Pipe family provided

a merchant who became Lord Mayor of London; and the Hoo family, from

Bradley, provided a Sergeant-at-Law – a lawyer somewhat above the

modern Queen’s Counsel and not much below the judges. Dr. Rowlands

refers to them as “lesser gentry”.

|