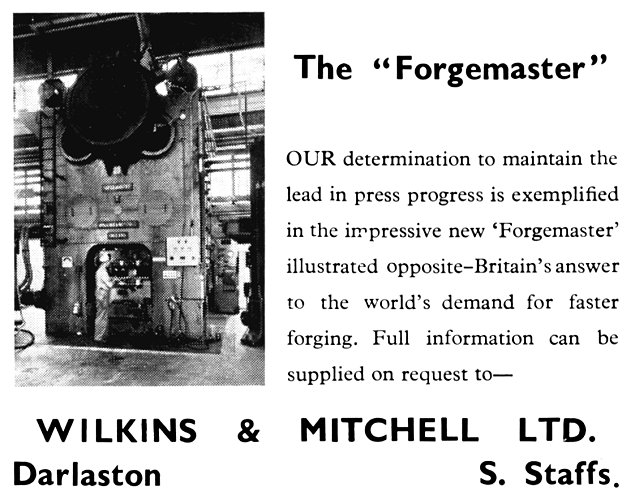

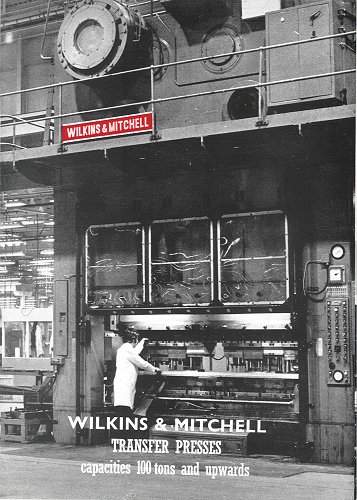

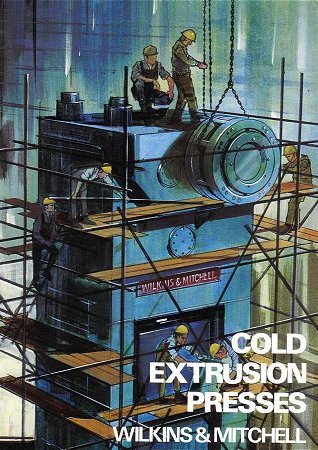

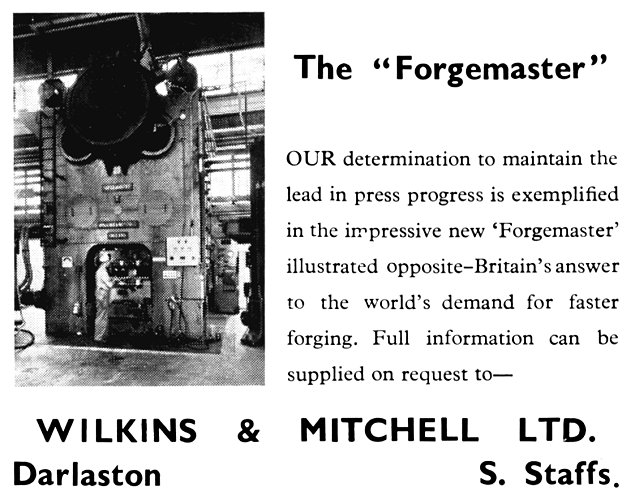

| Wilkins and Mitchell Limited became one of

Darlaston's leading engineering companies, employing

over 1,000 people. The family business in Richards

Street produced machine tools and power presses, for

either hot or cold pressing. They can be found in factories throughout

the world. |

| It all started in 1904 when two

friends, Walter Wilkins and Tom Mitchell from

Yorkshire, set

themselves up in business in a small factory in Bell

Street, called Phoenix Works, owned by nut and bolt maker Charles

Richards.

Walter, aged 29 had previously been

the head designer at Samuel Platts in Darlaston

Road, King's Hill,

and Tom aged 35, had a strong passion for

engineering, together with a great deal of technical

expertise, and the willingness to work hard for long

hours.

Walter and Tom started with a

few machines including a borer, an eight foot

planer, a milling machine, a slotting machine, a

twelve inch gap lathe, and a vertical drilling

machine.

Their first job was to

repair the steam roller belonging to Darlaston

Council.

|

Walter Wilkins in later life. |

|

The map opposite shows the

approximate location of Phoenix Works in Bell Street.

Walter

Wilkins and Tom Mitchell rented the factory from Charles Richards. |

| They soon received their first order for a piece

of machinery. It came from Rubery Owen and consisted

of several drilling machines. Around the same time they

received an order from Charles Richards for stripping

machines and a bolt heading machine. The bolt heading machine was the most advanced

machine of its kind, being considerably smaller than

the competition and about half the price. The two

friends soon formed a close relationship with both

companies. |

| 1907 proved to be a landmark year for the company, which

began when they received their first

order for machinery from a railway company. This

would become a common occurrence in

years to come, and provide the firm with a regular

income. The order, from the Birmingham Carriage

Company was for a slot milling machine.

The second

milestone was an order from Rubery Owen for a

blanking press. Walter designed the press to operate

hydraulically, with all of the hydraulic components

made in-house. As a result Wilkins and

Mitchell would go on to become one of the leading

manufacturers of power presses. They soon produced a

similar machine for Thompsons. The following year Walter and Tom built the first

British multi-head sole-bar drilling machine for the

Birmingham Carriage Company, a product that would prove

to be popular for the next 25 years.

By this time the

workforce had grown to two fitters, and an apprentice;

Tom’s son Joe.

|

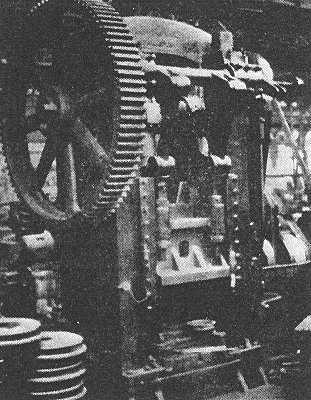

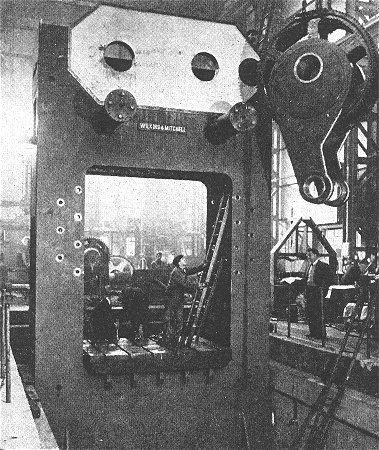

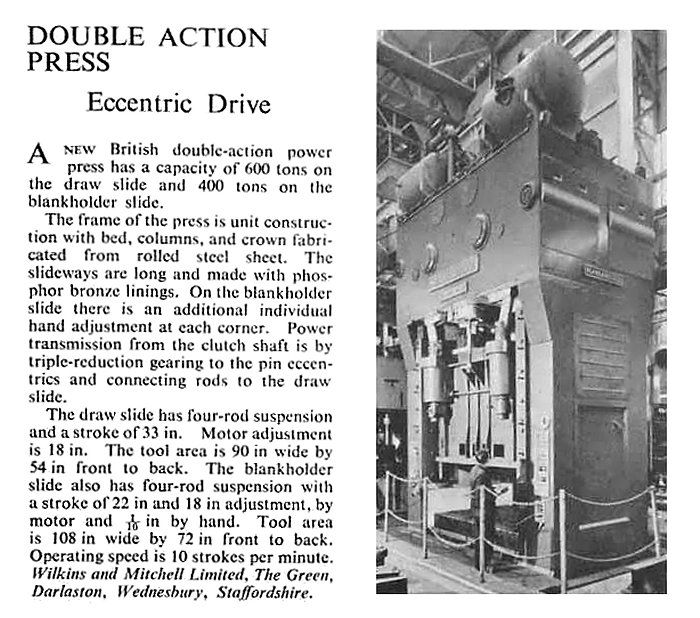

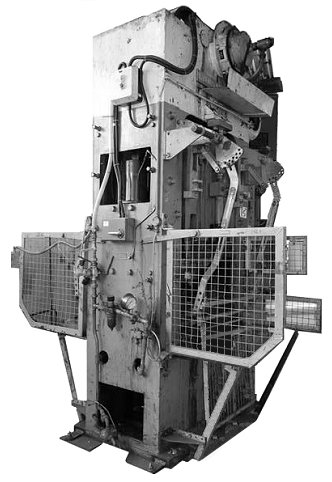

An early Wilkins and Mitchell double

action toggle press. |

|

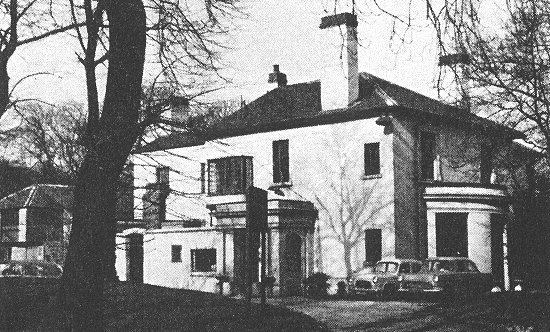

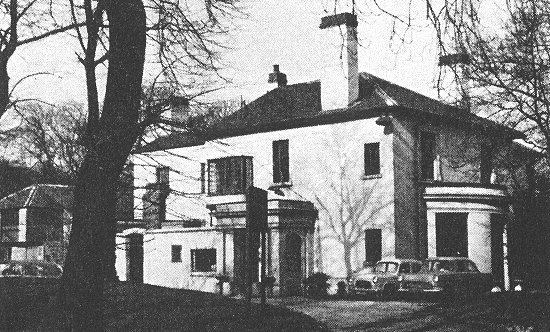

The Hollies, the Wilkins' family

home. |

1908 would be a memorable year in

another way. Walter Wilkins had become a great friend of

Charles Richards and his family, and had fallen in love

with his youngest daughter Louisa. Before the year was out they

were married, and the company’s employees were given an

hour off to attend their boss’s wedding. Walter and his

bride moved into their new home, The Hollies in Wednesbury. |

Expansion

By 1910 business was booming. There

were so many orders that they couldn’t cope in the

cramped conditions at the Bell Street factory. Luckily

the solution was at hand. Darlaston Green Works were

available at the time and so Wilkins and Mitchell

acquired the factory and renamed it “Phoenix Works”. At

the time they were receiving a lot of orders for special

machinery from railway carriage and wagon companies.

In 1911 Walter Wilkins and Alfred

Owen senior conceived the idea of a massive forming

press to cold press vehicle chassis frames, so

revolutionising production. Chassis frames were made

from around 10 gauge steel, and until that time had been

pressed hot. Although several similar presses were in

use in the U.S.A. nothing on this scale had been

attempted here. Walter’s design used a similar hydraulic

system to the one that he developed in 1907 for the

blanking press. The press, costing a mere £2,000 was

installed at Rubery Owen’s Darlaston factory in August

1913 and became an immediate success. It worked so well

that it continued in operation until 1970, and can be

seen today at the Black Country Living Museum.

Some earlier Wilkins and Mitchell’s

machines including a mechanical shear were still in use

at Rubery Owen’s factory until 1960, clearly

demonstrating the reliability of the company’s products. |

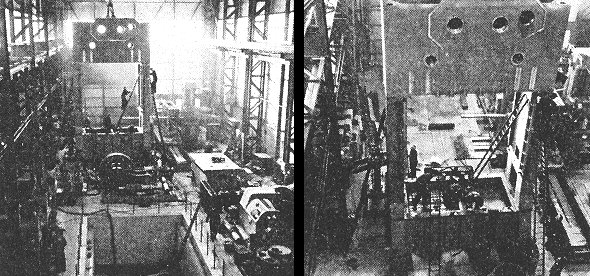

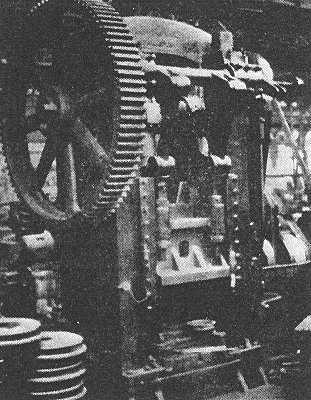

| The company's first 1,500 ton "upstroking"

press that was installed at Rubery Owen's Darlaston works in

August 1913.

It ran until 1970 and cold

pressed lorry chassis by raising steel blanks that were

pressed into the correct shape. |

The press

at the Black Country Living Museum, Dudley. |

|

A

Trip to America

The success of the huge press and

the close relationship between Walter Wilkins and Alfred

Owen led them to go on a fact finding tour of the

U.S.A. to explore the latest developments in machine

tools. Walter had always been impressed with American

engineering and their seven week tour would provide them

with plentiful opportunities to examine the latest

machines.

It nearly ended in disaster because

they booked their passage on a brand new luxury ship,

RMS Titanic, but luckily last minute business

commitments forced them to delay their departure. Had

they not done so, the history of manufacturing in

Darlaston would have been very different, with the

possible loss of two of the town’s most important

manufacturers.

Thanks to the delay they sailed on

RMS Lusitania and after arriving safely visited many of

the leading American machine tool manufacturers. They

also inspected some of the factories belonging to the

largest vehicle manufacturers including Ford, General

Motors, and Studebaker. As a result of their successful

tour Alfred Owen conceived the idea of producing vehicle

chassis and other motor components for British vehicle

manufacturers at highly competitive prices. Similarly

Wilkins and Mitchell would go on to build competitively

priced, state of the art machines for the same

manufacturers.

The

War Years

For the first two years or so of

the First World War, the manufacture of special purpose machine

tools and presses continued much as before, except that

production had to be greatly increased to keep-up with

the demands of the munitions industry.

At the beginning of the war Wilkins

and Mitchell employed between 60 and 70 people who

worked flat out to supply the needs of their customers.

Unfortunately the constant pressure to keep up with the

demand for the company’s products became too much for

Tom Mitchell, who in 1916 broke down under the strain and retired

to Blackpool. He sold his interest in the firm to

Walter, who also came under a

lot of pressure.

Apart from the day-to-day running of

the company, he became involved in other work. He was

asked to go to the War Office in London to assist in

vital war work. As a result he became a consulting

design engineer, assisting Dr. Frank Lanchester in the

design of a compact transmission for tanks that would

allow more room inside for the crew. As a result he

built an experimental tank at the Birmingham Carriage

Company.

He also carried out consultancy

work for other companies, which resulted in him dashing

all over the country. In 1916 his work load increased

even more when Wilkins and Mitchell designed and built

their largest press to-date. Walter was so hard pressed

that he even had 3 or 4 draughtsmen working in his

dining room at home, in order to complete the job on

time. The hydraulically operated press was delivered to

Rubery Owen in June.

By 1916 Wilkins and Mitchell were

also producing other war work including drag lines for

artillery, fuse caps, and gear trains for tanks. The

company also machined cradles for 18lb. field guns and

for naval 12lb. anti-aircraft guns for Wolsley Motors,

at the time a subsidiary of Vickers-Armstrong. Walter

revolutionised the production by making it far more

efficient. At Vickers-Armstrong one man took 120 hours

to machine a single gun cradle. Walter reduced this time

to just 12 hours by using three men to operate machines

and jigs of his own design. This meant that 10 of the

much needed gun cradles could be machined in the time

that it previously took to do just one.

Wilkins and Mitchell also began to

produce the ‘Lightening’ car jack, which Walter had

previously designed in about 1912. He originally set his

brother George up in business to manufacture the jacks

in a small factory at Moxley in partnership with John

Richards. During the war production was transferred to

Phoenix Works.

|

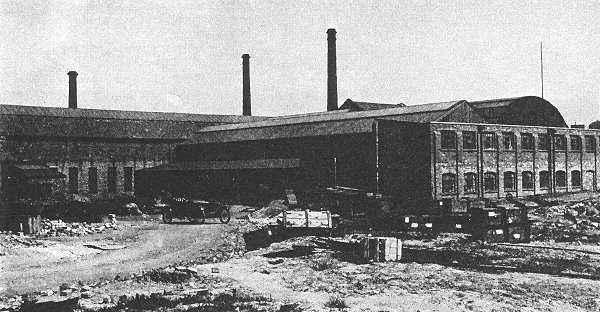

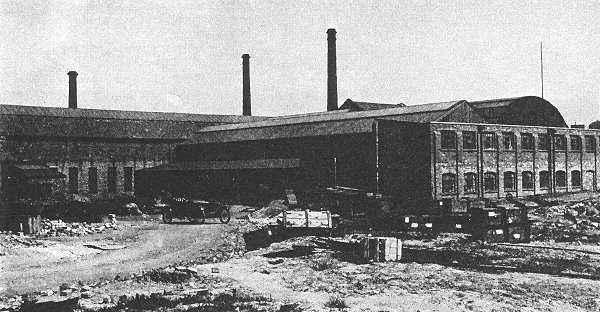

The Darlaston factory in 1917 with

Walter's Saxon car in the foreground.

|

After the War

The company, like many others had

greatly prospered thanks to the plentiful supply of

wartime Government contracts. Walter Wilkins realised

that the contracts would abruptly end when hostilities

ceased, and that large quantities of cheap machine tools

would be put-up for sale when they were no longer

required for war work. Something had to be found to tide

the company over until things returned to normal.

As a result he arranged to build mechanical stokers for

Vickers-Spearing, a subsidiary of Vickers-Armstrong who

had a good relationship with Wilkins and Mitchell thanks

to their work on the gun cradles. The mechanical stokers

consisted of wide endless belts that slowly revolved and

transported coal from a hopper to the furnace at one

end, then carried the burnt ash out at the other.

The contract nicely filled-in the

gap at the end of the Government orders, and provided a

smooth transition from war to peacetime work. There was an 18 month backlog of

orders to get through. At the same time new orders were

arriving, mainly for specialised drilling machines for

Railway wagon and carriage companies.

Many of the orders were for

sole-bar drilling machines, some of which were 50ft.

machines. Other orders were for hydraulic presses, used

in the production of heavy lorry chassis. |

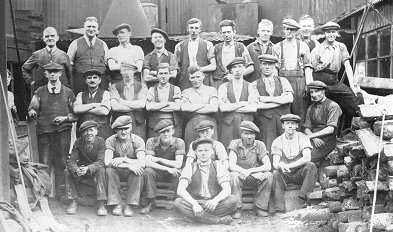

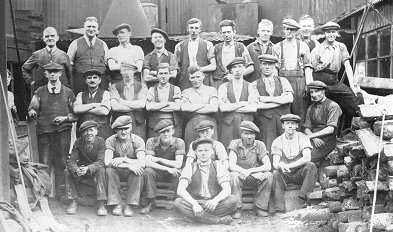

| A photograph of some of the

workers at Phoenix Works in Bell Street, in the late

1920s. The second from

the left in the middle row is John Gibbons.

Courtesy of Brian Groves. |

|

|

Another photograph taken at

Phoenix Works, possibly at the same time as the one

above.

The first lady on the left in

the middle row is Mary Gibbons.

Courtesy of Brian Groves. |

|

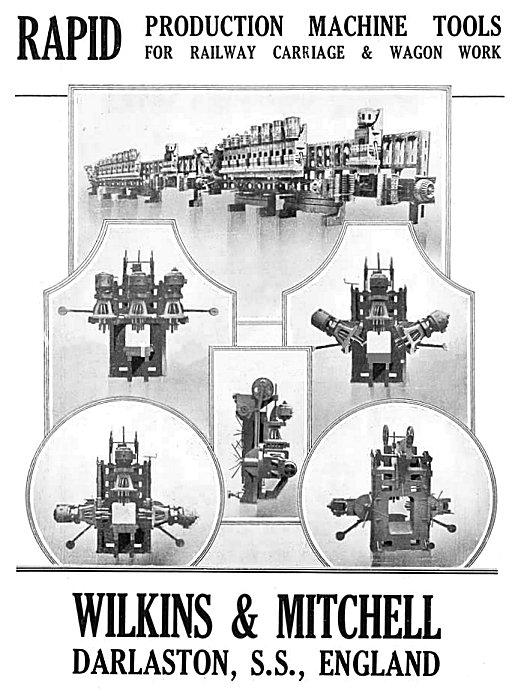

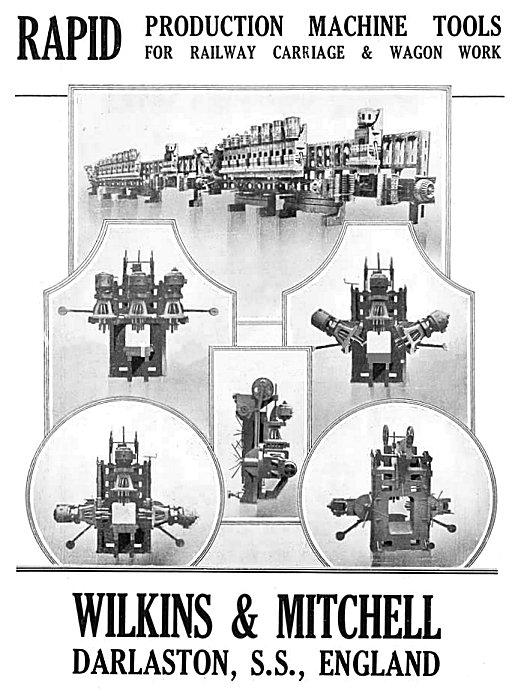

An advert from The Railway

Gazette, 22nd November, 1926. |

|

New

Products

Walter Wilkins was as prolific as

ever. He had a small experimental workshop at home in

which to develop new products, and even designed and

made a special drawing board for use in bed, so that if

an idea occurred to him during the night he could

instantly put it on paper. He began to develop a rotary valve

V8 petrol engine, but unfortunately never completed the

work because of lack of time. He also designed a

multi-head group drill, an early form of automated

machine tool. A number of them were sold to the

Hotchkiss Motor Company, the manufacturer of engines for

Morris.

It carried-out the complete machining of a Morris

cylinder block, and consisted of a series of

machines that were coupled together. The cylinder blocks

travelled on a track between the machines, which quickly

carried out the fifty five operations that were

necessary. The installation was one hundred and eighty

one feet long, eleven feet wide, and eleven feet high,

and powered by eighty one electric motors. It cost

around £13,500. Another of Walter's inventions was the under-drive

press.

In 1928 Walter’s eldest son, John,

joined the company as an apprentice pattern maker,

earning two pounds a week. Within a few years his three

brothers Henry, Edward, and Philip would also join the

family business. Henry

married Joyce Winn, daughter of factory owner, W. Martin Winn. Walter became interested in the

Rotarian movement and along with a few friends founded

the Rotary Centre in Wednesbury.

|

|

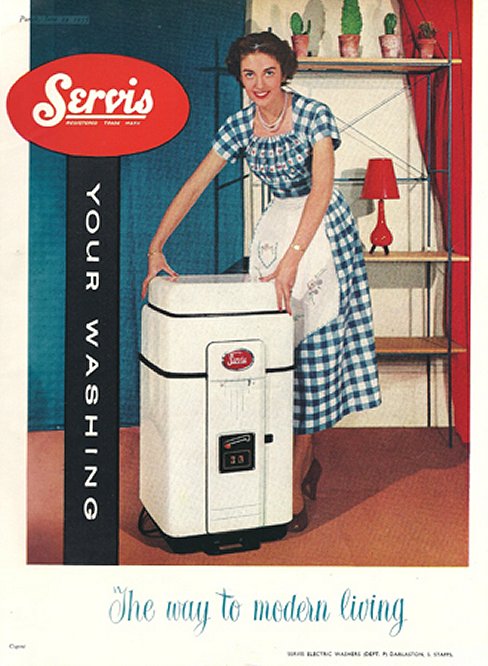

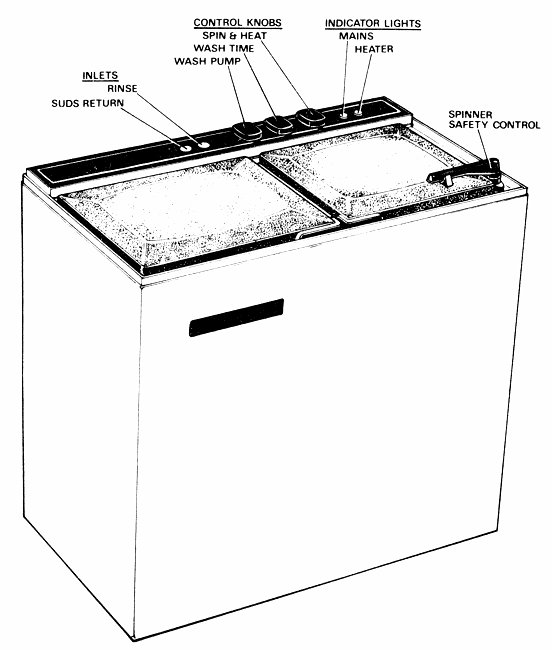

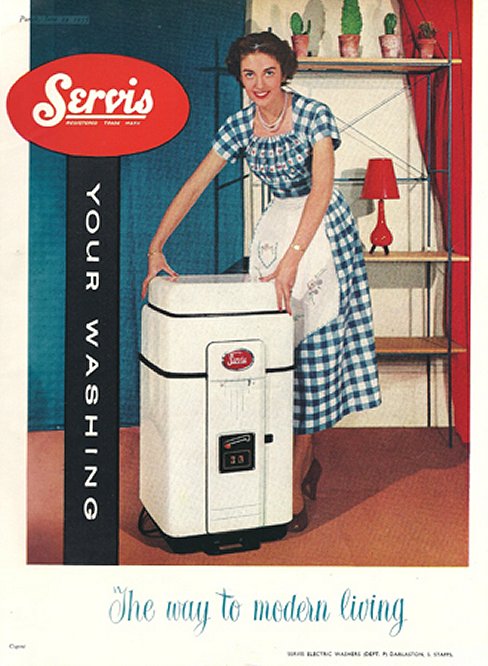

Around 1926 Walter turned his

attention to washing machines, which he considered would

be a good addition to Wilkins and Mitchell’s product

range to ensure the future growth of the company. He

founded Servis Limited in 1929 to manufacture them, and

in the

spring of 1930 took his family on a tour of the

U.S.A. While there he visited several factories

including a couple that made washing machines. When the

family returned home the Wilkins boys attempted to

perfect their prototype washing machine. They had

initial problems with the drive, but once they had

successfully tried a ‘V’ belt, they were on to a winner. The new machine was launched at the

Ideal Home Exhibition and the Preston Agricultural Show.

By that time Walters’s sons Henry and Edward had joined

the company and greatly assisted in selling the machines

at exhibitions.

During the recession in the 1930s

the washing machines helped the company to keep going.

The demand for machine tools fell and so workers from

that part of the business were temporarily used to

tool-up for mass production of Servis washing machines. At the

height of the recession the company made a small loss,

but still managed to keep going. |

An advert from 1934. |

|

An advert from 1938. |

The first Servis machines were built using the stock

of unsold machine tools in the factory, and the Model

‘A’ soon appeared. It was quickly followed by the

improved Model ‘B’ which sold extremely well.

The first cabinet machine, the forerunner of present

day machines, was the Model ‘E’. Like its predecessors

it sold well, and assured the future of the company.

A separate department was soon set-up where the

machines were repaired by skilled mechanics who were

specially trained to work on the whole range of Servis

machines.

By the late nineteen thirties the depression had

ended, and manufacturing flourished. Heavy presses and

washing machines were produced in adjoining bays, and

newly designed blanking and drawing presses were first

tested on the Servis production line. |

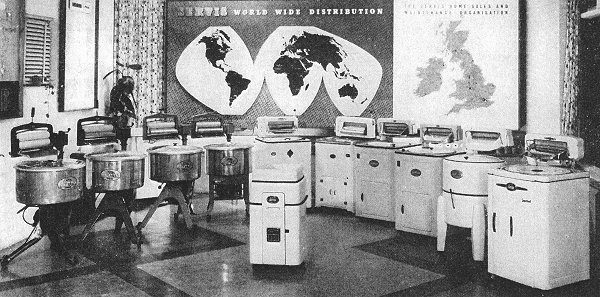

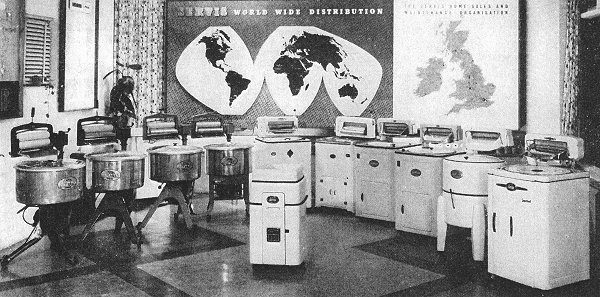

The Servis museum showing a display of

early and later machines.

An advert from the mid 1950s. Courtesy of

Christine and John Ashmore.

|

At the beginning of the Second

World War washing machine production was turned-over to

the manufacture of ammunition boxes, while the heavy

tool division concentrated on building extrusion presses

for armaments, and a variety of specially designed

machines for ordnance factories.

At the end of hostilities when the

war contracts were being wound-up, and the production of

washing machines began again, Walter Wilkins was taken

ill. He was in his seventieth year, and his doctor

advised him to take things easy. Being a

workaholic made this an impossibility. He had boundless

energy and an active mind, and carried-on regardless,

working tirelessly until his death in September 1946. |

| After his death, his widow Louisa Wilkins took over

the running of the company. A position she held for many

years until failing health forced her to retire.

The company was then managed by her four sons, John

C. Wilkins who became Chairman, Henry R. Wilkins and

Edward W. Wilkins who became joint Managing Directors,

and Philip A. Wilkins, Works Director.

They were joined on the Board by two non-family

members, A. F. Gadsby, Financial Director, and A. T.

Thorley, Sales Director. |

Louisa Wilkins. |

|

|

|

|

Mr. Edward W. Wilkins. |

|

Mr. Henry R. Wilkins. |

|

|

|

|

|

Mr. John C. Wilkins. |

|

Mr. Philip A. Wilkins. |

|

|

|

|

|

Mr. A. F. Gadsby, F.C.A. |

|

Mr. A. T. Thorley. |

|

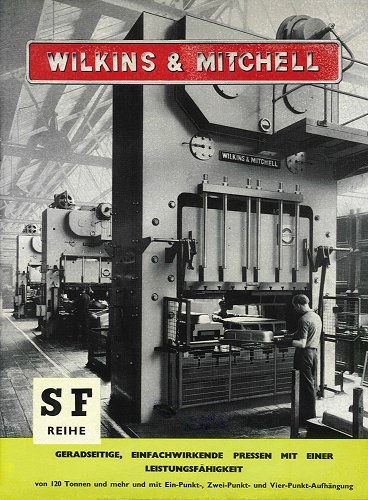

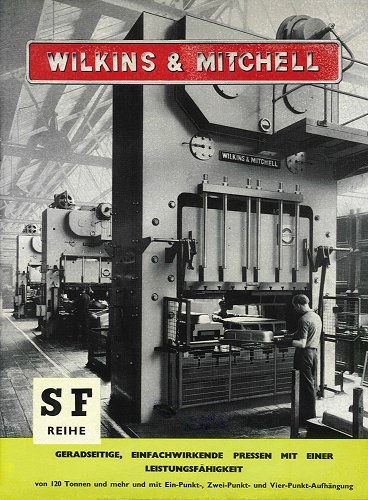

| Under their control the business continued to grow.

The machine tool division no longer took orders for

special machinery, but was devoted to the design and

production of power presses. New plant was installed for

the purpose, and factory extensions were built. In 1947

the company’s products were exhibited for the first time

at the British Industries Fair, and the following year

at the Canadian Trade Fair. Many new orders came as a

result of the exhibitions, and from then on Wilkins and

Mitchell’s presses and washing machines would be seen on

display at many trade fairs, both at home and abroad. |

|

An advert from 1954. |

|

An advert from 1955. |

|

Another advert from 1955. |

|

An advert from 1956. |

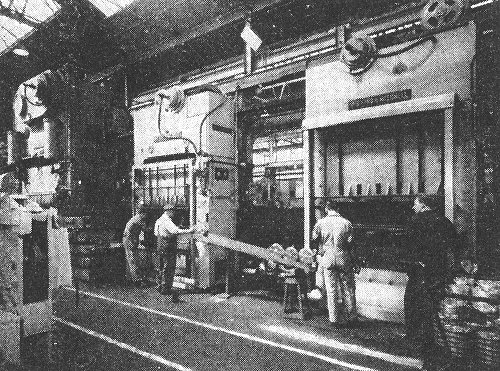

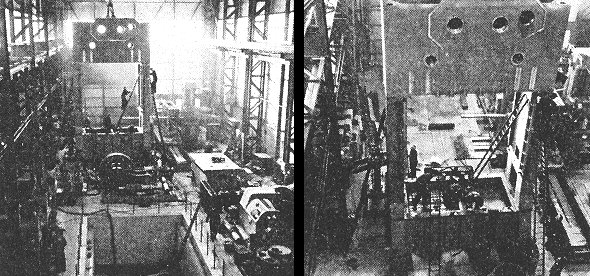

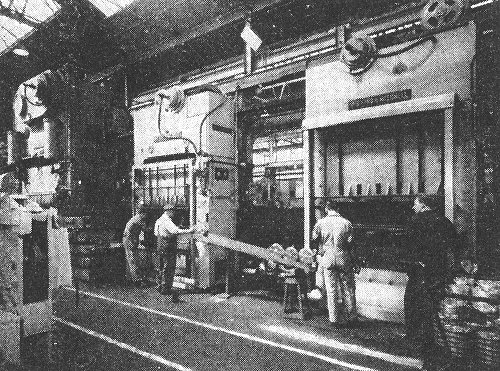

Presses under construction in the Machine

Tool Assembly Bay.

| In the late nineteen forties washing machine

production suffered from the nationwide shortage of

sheet steel. In order to meet the growing demand the

company designed the Servis Model ‘R’, built from the

available steel strip. Many thousands of Model ‘R’s were

produced and sold at home and abroad. Sales were so good

that the model remained in production for many years. In

order to qualify for an increased allocation of sheet

steel, the company extended its overseas market and

designed a new machine with all the latest features,

which would appeal to foreign dealers, and compete well

in the highly competitive market. |

|

The air conditioned spray plant at

the Servis factory. |

Because of the company’s growing sales, more staff

were needed and new offices were built to accommodate

them. By the early nineteen fifties space in the

factory was in short supply. Production had rapidly

increased and so a new Servis factory was built at

Darlaston Road, King’s Hill for the production of

washing machine parts. |

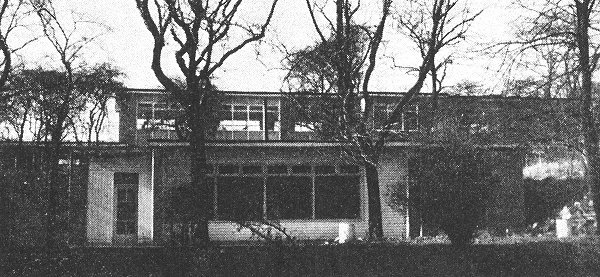

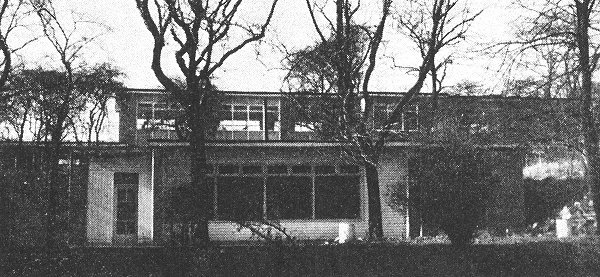

| The Servis Sales Training wing and the Servis

Development Department moved to a new building in the

grounds of the Hollies, in Wednesbury, the former home

of the Wilkins family.

The house itself was converted into offices for the

Servis Sales Administrations staff. |

Part of the Servis Press Shop. |

| Memories of Wilkins

and Mitchell Derek Thorley, who was born in October

1938 in Herberts Park Road, worked for the company.

After leaving Slater Street School in the early 1950s,

he joined Wilkins and Mitchell as an apprentice

engineer, and attended Wednesbury Technical College as

part of the company's day release scheme. He initially moved around

the factory, and worked in several departments to gain

experience.

When he joined the firm, there was no official

apprenticeship scheme. Around two years later he joined the

company's apprenticeship

scheme when it was introduced. The

scheme, run by training supervisor William E. Howells

(Billy), was based in an old electricity sub-station

building in Victoria Road, which is now occupied by the

4th Darlaston Scout Group. The building had previously

been used by Wilkes the printers, and the Wilkins and

Mitchell stationery stores. The firm installed a range of

machinery in the building, on which to train the

apprentices. William Howells arranged factory visits to

many firms including Rubery Owen, Cadburys, and Chubbs.

During his final year as an apprentice, Derek worked in

the Servis

development department at the Hollies, which was

managed by Derek's uncle, Vince Thorley, and consisted of

an engineering workshop for building prototype

machines, and a test lab for testing component

parts. He also worked in the drawing office, run by Bob

Peach, which was above the development department.

Derek left the company in 1961. |

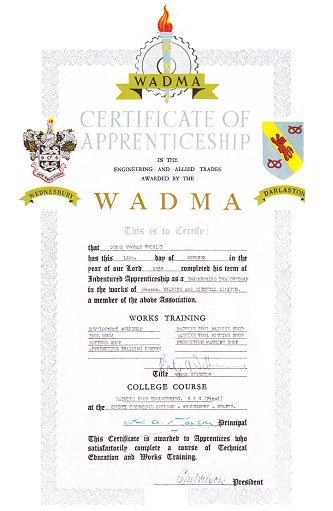

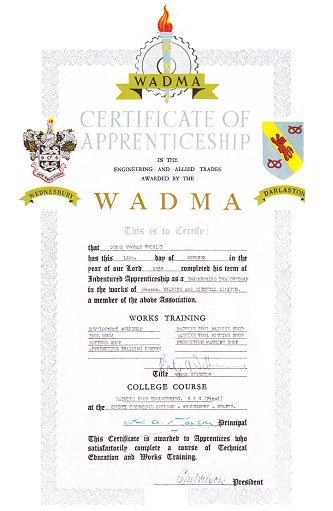

|

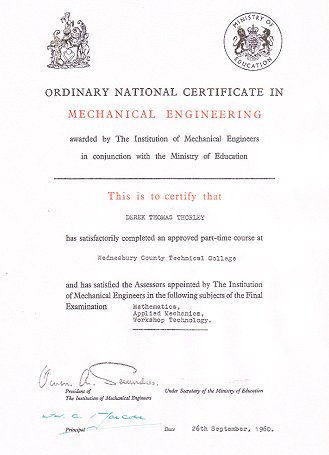

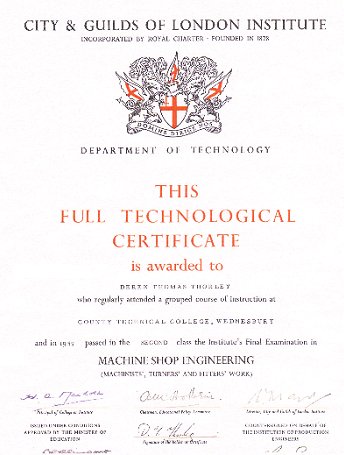

Derek Thorley's certificates that he obtained during

his time as an apprentice at Wilkins and Mitchell..

The one on the left was awarded when he completed his

apprenticeship as an engineering draughtsman in October

1959. He had trained in the development workshop, the

tool room, the pattern shop, the machine tool machine

shop, the machine tool fitting shop, the production

machine shop, and the apprentice training centre.

The two certificates below are his City and Guilds final

certificate in Machine Shop Engineering, and his

Ordinary National Certificate in Mechanical Engineering,

both awarded after attending courses at Wednesbury

County Technical College.

The bottom two certificates were presented at the

beginning and end of his apprenticeship.

During his apprenticeship he also helped out on the

production lines at the Kings Hill Servis factory, known

as No. 2 factory.

Derek greatly enjoyed his time as an apprentice and

has fond memories of his time there. |

|

|

|

A group of Wilkins and Mitchell apprentices on a

day out to Cheddar Gorge in about 1955. The names

are as follows:

Back row left to right:

?, Patrick Turley.

Front row left to

right: Brian Rutter, Brian Proffit, Brian

Harrison, Graham Sheffield, Brian Jackson, Anthony

Dean, Charles Dickens, and Keith Amos.

Photo and names courtesy of Derek Thorley and

Anthony Dean.

|

|

Later Years

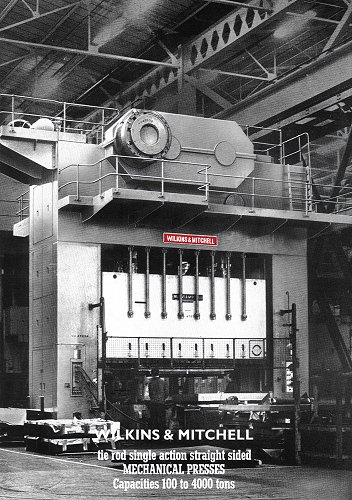

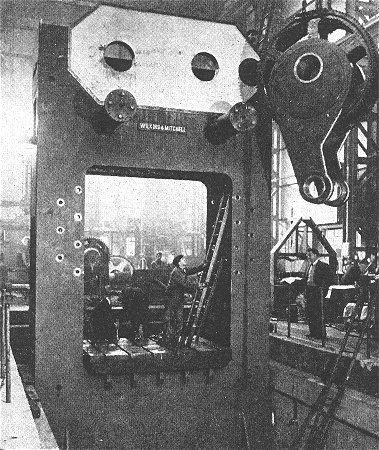

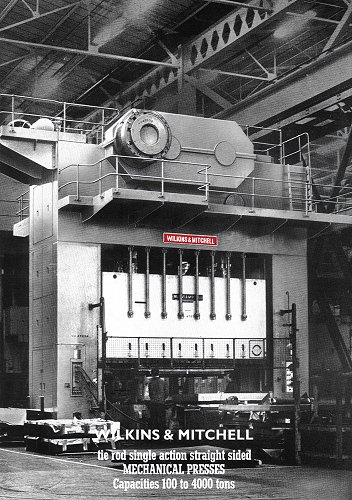

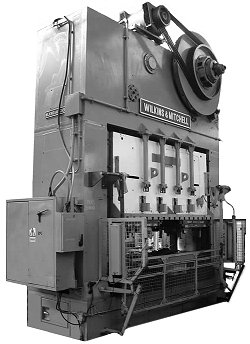

New extensions were built to the

power press factory at Darlaston including an assembly

shop with a crane capacity of one hundred tons. The

giant power presses could for the first time be entirely

built at the factory, rather than using sub-contractors

for some of the work.

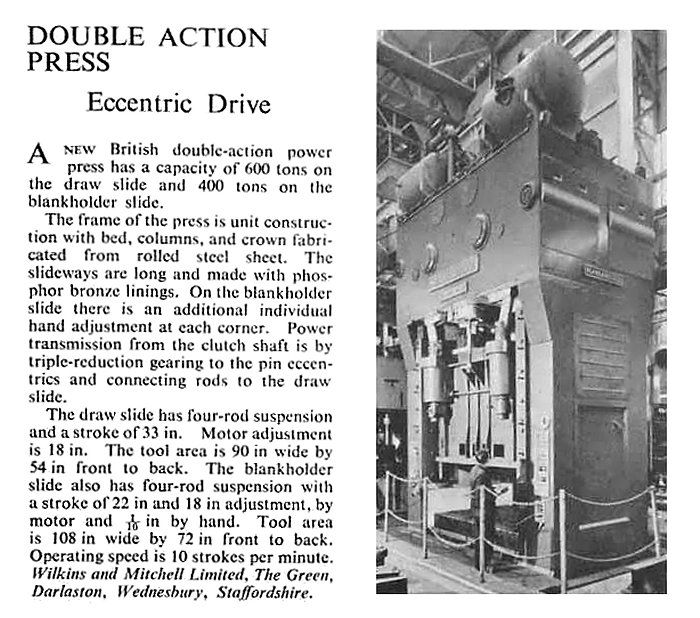

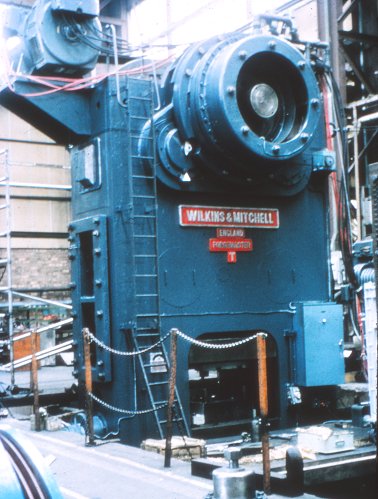

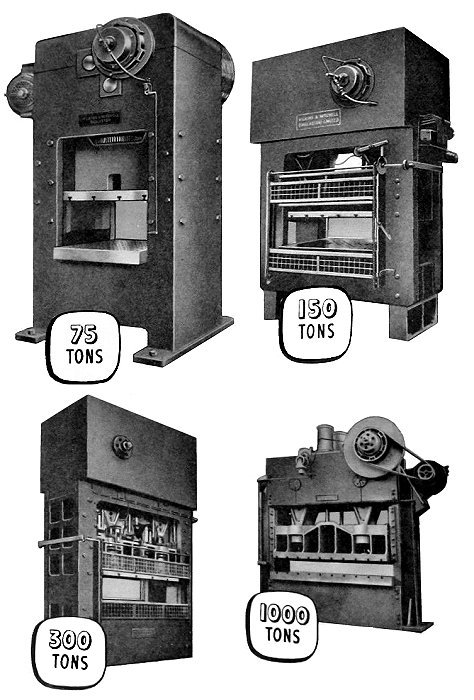

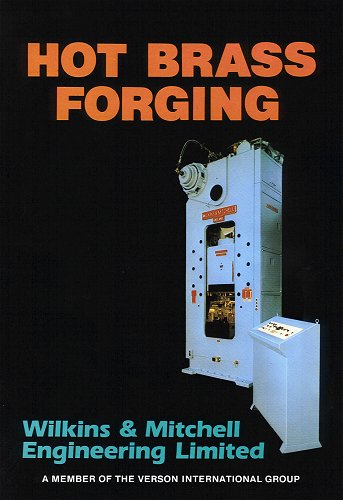

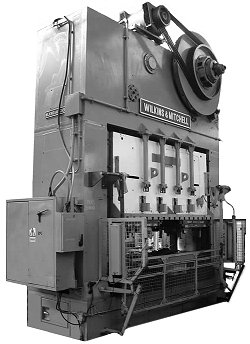

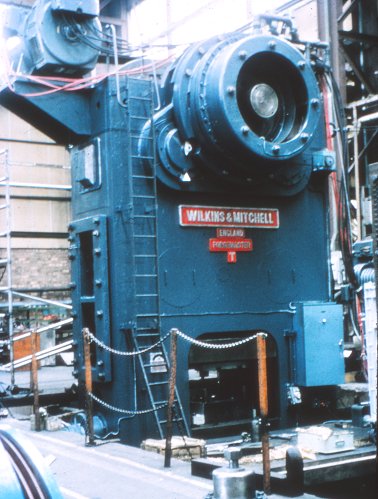

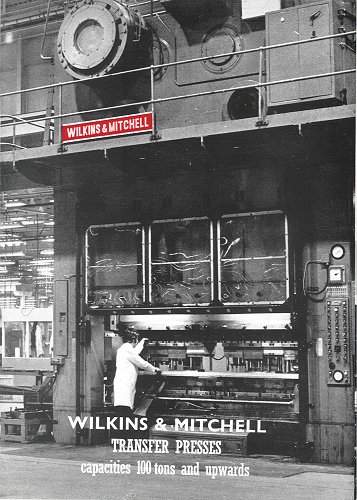

Wilkins and Mitchell presses became

well known and respected throughout the world. Single

and double action presses were produced for a wide range

of industries including the motor industry, the forging

industry, the aircraft industry, and the domestic

appliance industry. The special machinery for the

forging industry included billet shears, forging rolling

machines, high speed forging presses, and clipping and

setting presses. The company’s presses also

revolutionised the hot brass stamping industry with a

specially designed sub-press, capable of producing

multi-cored components in a single operation at a much

higher production rate than had previously been

possible.

An advert from the mid 1950s.

Courtesy of Christine and John Ashmore.

Presses from 100 tons to 6,000 tons

were built at the Darlaston factory, where a team of

highly skilled mobile service engineers were based to

carry out all, except major overhauls on the company’s

presses. Wilkins and Mitchell always ensured that

“down-time” on their products was reduced to a minimum.

A modern London office was opened

in Park Lane where a display of Servis washing machines

could be seen. The premises also housed the Power Press

Export Section. The overseas market was extremely

important to the company. The Wilkins brothers regularly

visited overseas agents and kept them informed of the

latest developments. In the nineteen fifties an

agreement was made with an Australian company for the

manufacture of Wilkins and Mitchell power presses under

license. |

The new building in the grounds of The

Hollies.

An advert from 1960.

|

By the 1960s thousands of Servis

washing machines were made each week. There were over

300 mobile mechanics, whose Servis vans became a common

sight on British roads. They were supplied from twenty

one regional depots throughout the country. The Servis

personnel covered over three million miles annually to

support the company’s claim that Servis washers were

serviced wherever they were sold.

A subsidiary company called Wilkins

Servis was set up to manufacture washing machines in

Australia, and there were distribution companies in

Switzerland and Belgium, and a network of agents

covering fifty overseas markets.

The long standing apprenticeship

scheme was reorganised with the opening of a fully

equipped training school. A company newspaper with a

circulation of 12,000 copies was published twice a month

and sent to all employees, dealers, and power press

customers. The company celebrated its golden jubilee in

October 1954 and became a public company with about

thirty percent of the ordinary share capital for sale.

For the jubilee celebration, the company hired the Civic

and Wulfrun halls in Wolverhampton, and laid-on coaches

to get the employees there. There were staff from all

over the country who enjoyed a dance with a live dance

band, and entertainment featuring Tommy Cooper and a

roller skating duo. In the late

1950s a large piece of land was purchased at

King’s Hill next to the existing factory, for an

extension to the factory and the building of a new

office block. At the same time development of what was

to be another successful product, the Servis ‘Super

Twin’ began. The Servis machines were at the expensive

end of the market along with such names as Bosch, and

gained a high reputation for reliability. |

|

The front of the factory with the

large press shop assembly bay in the background. |

The 1960s were good years for the company, sales

remained high, and new products were developed.

Unfortunately things started to go wrong in the

recession during the late 1970s.

Orders were few and far between, which resulted in

the business going into receivership in the early 1980s. |

|

In 1982 the

newly formed UK manufacturing group, Verson

International run by American businessman Tim Kelleher

acquired Wilkins and Mitchell from the receiver.

The group’s main companies were Wilkins and Mitchell,

and Bronx Engineering of Lye, who were acquired in 1986.

By the late

1980s group sales were approaching £40 million and a

good future seemed ensured. In 1987 profits were

£750,000, compared with £176,000 in 1986, and this

steady growth continued for some time.

Tim Kelleher

removed the barriers between the shop floor and the

management team. He believed that the company’s main

asset was the skilled workforce. Director’s dining rooms

were closed, their privileges were removed, and all

non-essential company cars were sold. A manager could

loose his job if he didn’t know every employee by his or

her first name. |

A hot forging machine. |

|

The bull gear and eccentric being

fitted to a 1,500 ton press. |

At Darlaston the

group planned to build a new larger factory for Wilkins

and Mitchell on a 15 acre site in Willenhall Road,

formerly occupied by Wellman Cranes. The existing

Richards Street works would house a new specialised

fabrications company.

The new factory

with a workforce of nearly 300, cost £6 million and was

opened on 28th November, 1990 by John Major. The company’s Managing Director

was George Paxton, who previously ran Verson AI in

Inverness.

The company name

changed to Verson Wilkins, and by the end of 1990 orders

for power presses reached nearly £7 million. The orders

included a huge 2,650 tonne trimming press for a forge

in Lincoln, the largest power press built by the company

at that time. Many of the orders that followed were for

vehicle manufacturers, including Nissan at Tyne & Wear;

A.C. Rochester who were part of General Motors; and a

huge 3,000 tonne “try out” press for Toyota. |

|

Unfortunately

the fortunes of UK car manufacturers were on the wane

and orders fell. By the middle of 1993 Verson

International was £3.5 million in the red, not helped by

a very significant loss at Verson Wilkins. As a result

the group merged with Clearing UK and reduced its

product range. The Darlaston subsidiary now became known

as Clearing International. In November, 1994 about 70

jobs were shed at Darlaston and the future looked very

uncertain. Quite a stir was caused in the works in

December of that year when the factory became the

location for the American film crew who were shooting a

film about the Iraqi super gun entitled “The Doomsday

Gun”.

In 1995 about

half the employees lost their jobs at the Darlaston

factory when the workforce was greatly reduced. At the

time they were producing presses from 300 to 1,500

tonnes as standard, and up to 2,500 tonnes to special

order. The company also refurbished their old products.

By 1996 the deficit amounted to £5.8 million and the

group decided to sell Darlaston based Clearing

International. The Darlaston company then formed a

partnership with Scarborough based Bootham Engineering,

but the downturn in the motor manufacturing industry

continued and the decision was taken to close the

Darlaston factory.

|

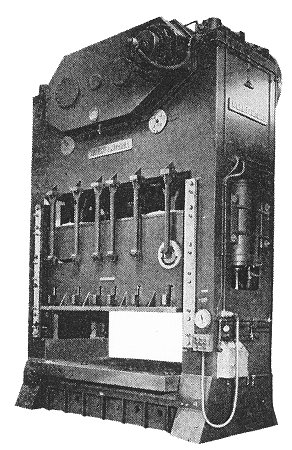

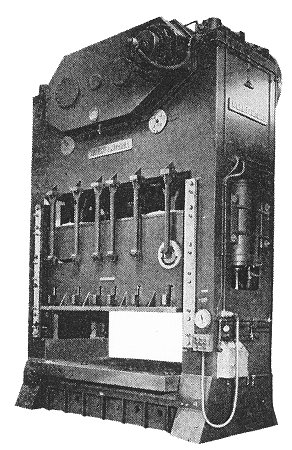

A T.R. Series blanking and drawing

press. |

|

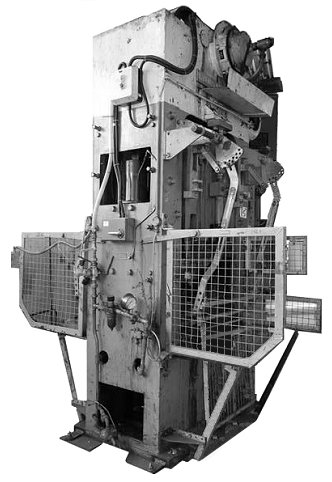

A 300 ton double sided power press. |

As a result the factory closed,

with the loss of 64 jobs, on 2nd April, 1999. Another nail in the coffin

for Darlaston’s manufacturers, who were once known

throughout the world for their quality products. The story doesn't quite end there. After the closure of

the Darlaston works, Bootham

Engineering moved its offices to Bloxwich.

In

2003 the company was taken over by Muller Weingarten UK

Limited, and in October 2005 the company moved to

Quayside Drive in Walsall.

In March 2008, Muller

Weingarten UK Ltd and Schuler UK merged to form the new

company Schuler Presses UK Limited. The company services

and supports Wilkins and Mitchell presses. |

|

|

|

|

Courtesy of Mark Foster. |

|

|

|

|

Courtesy of Mark Foster. |

|

|

|

|

Courtesy of Mark Foster. |

Assembling a gearbox for the Cable

Belt Company in the 1980s. |

|

|

A Wilkins and Mitchell large power press. |

|

| Wilkins and Mitchell's other factory, Servis at

Darlaston Road, King's Hill had been extremely

successful until the early

1980s.

In the early 1980s they produced the first

washing machines in the world to use microprocessor

control, in the successful "Quartz" range.

The company

got into difficulties during the recession and went into

receivership. In July 1982 it was acquired by Centreway

Industries, which saved over 1200 jobs. In 1983 there

was a huge fire on part of the King's Hill site that

caused much damage.

The company went into receivership a second time in

1985 and was purchased by the Gooding Group in April

1985, with

assistance from the West Midlands Enterprise Board,

which provided £750,000 towards the purchase. 400

of the 600 workers at the factory were then able to return to

their jobs.

In December 1987, the Gooding Group decided to sell

the business, which had failed to rise to expectations

and acquire a large enough share of the British market,

even though there were annual sales amounting to £30m. |

An advert from 1963. |

| There was a management buyout led by Graham

young and Kevin Moat, each owning 44.5 percent of

the company. Graham young was Managing Director and

Kevin Moat was Sales Director. They hoped to expand

their sales in Germany and Belgium. Unfortunately

things didn't work out as planned and in March 1989

the business again went into liquidation.

A new

company, Servis UK was formed in November 1990 and

purchased by Antonio Merloni in 1991. Manufacturing ceased at the

King's Hill factory, which became a spare parts centre,

and dealt with repairs.

In 1995, the workforce was greatly reduced, and

about half the employees lost their jobs. The

factory closed in October 2008, by which time there were only 50

members of staff. Sadly, the factory was demolished in

2011, and by

April of that year it had completely disappeared. It was

a tragic end for a Darlaston company that was once the largest local

employer, producing high quality products that were well

respected and well known, almost everywhere. |

The empty Servis factory in November 2008.

|

The Servis Quartz 1000 Deluxe

microprocessor controlled machine that's on display at

the Black Country Living Museum, Dudley. |

|

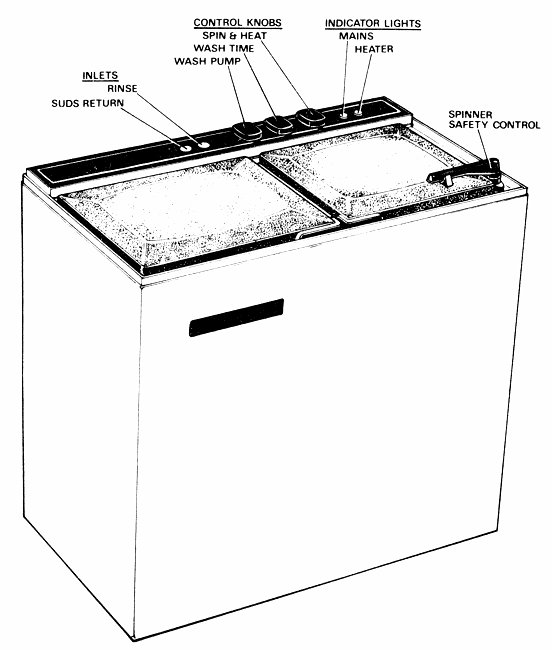

The Servis Supertwin 108. |

|

Another view of a Servis Supertwin

108 showing the controls. |

|

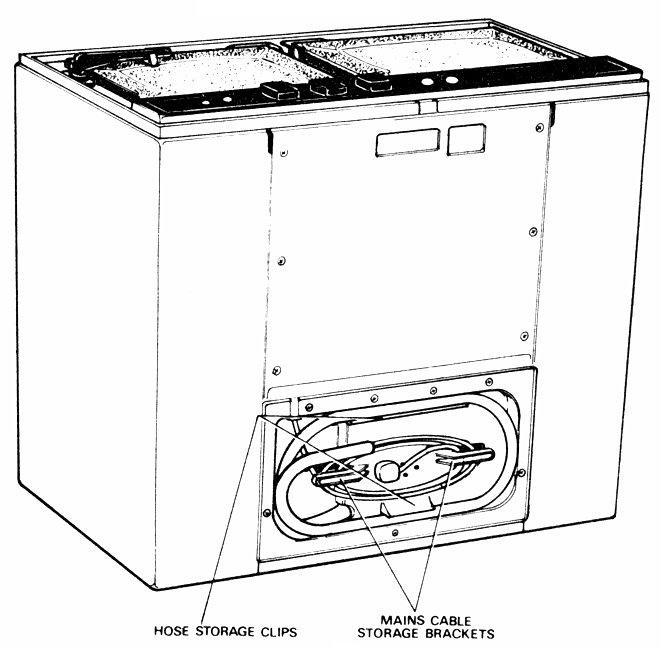

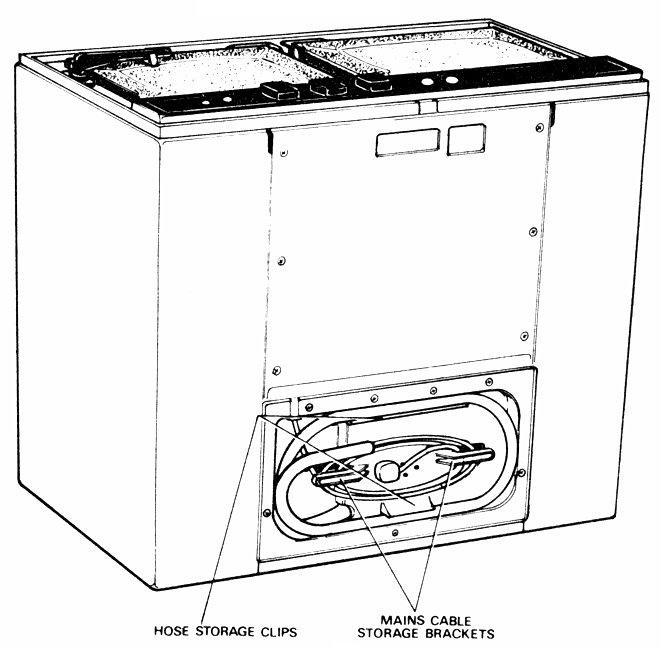

A rear view of a Servis Supertwin

108. |

The empty factory in 2009.

The main entrance in 2009.

Another view from 2009.

The Servis factory in the 1960s.

The same view in April 2011.

All that remained of the Servis factory in

April 2011.

All that remained of the Servis factory in

April 2011.

I would like to thank Mark Foster of Schuler Presses UK Limited for

his help in telling this story. He kindly provided the information

about the company up to the Second World War, and many of the

illustrations. I would also like to thank Bill Rayson who worked at

the company for 36 years,

who also worked there, and Peter Richards who supplied a lot of

information.

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|