Working at Bushbury Shed

This is an article that was in two parts. The first part was in edition 1

and part 2 was in edition 2.

The L.N.W.R. built a shed at Bushbury as early as 1859, replacing the

first structure with something more substantial in 1883. The new shed

was doubled in capacity, holding 24 engines, but was still not large

enough. Bushbury was always overshadowed by the Great Western presence

at Stafford Road, only a short walk away. It had its own distinctive

atmosphere though, and has been aptly described as "a family shed", and

so it was, with fathers, sons and uncles all working together.

The same surnames appear in Bushbury, marked "railwayman" as far back

as the 1881 census, probably working at the earlier shed on the same

site. Moving on was a fact of life for Great Western men in search of

promotion, Wolverhampton for instance became home for many ex-Cambrian

and Taff Vale railway men, but life at Bushbury was more predictable and

the order of things changed little over the years.

The enlightened attitude of the G.W.R. towards such things as social

amenities and pensions for ordinary employees is well known. The

L.N.W.R. was less forthcoming in such matters and the working conditions

at Bushbury were not of the same standard, with a corresponding lack of

after work activities. What the men had they provided for themselves.

Alexander Staveley Hill, the Conservative M.P. built a school for the

children of Bushbury which opened in 1880, most of the students being

the sons and daughters of railway men. This school later served as the

venue for small concerts organised by the L.N.W.R. employees at

Bushbury.

|

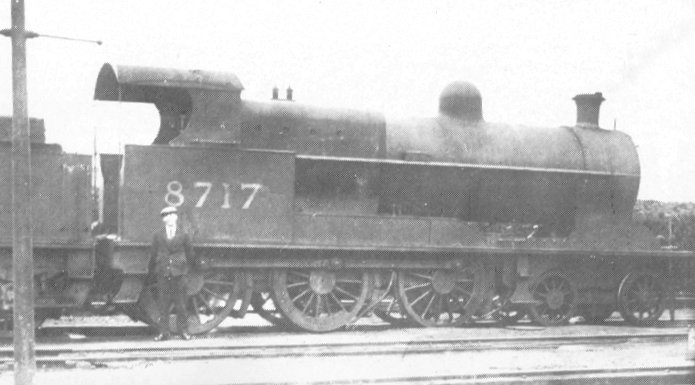

Bushbury timekeeper Sid Newill stands before

"19 inch" goods 4-6-0 No. 8717 (c. 1930). These engines were used on

the "double home" trips to Liverpool. These 4-6-0s were replaced in

the later 1930s by 'Super D' 0-8-0s, but their old duty was still

known as the "19 inch link". Photograph courtesy of Joyce Batchelor, Nee Newill. |

| For instance in September 1892 the Bushbury Loco

Sick Society, twenty pounds in the red due to the recent flu

epidemic, ran a series of concerts and choral works there, the

entertainments being provided by the newly formed "railway glee

class". In 1897 the first of the "Bushbury Railway Servants" Annual

Concerts took place, the venue over the years usually being the

assembly rooms of the Electric Construction Company in Showell

Lane. The proceeds were always in aid of the "Railway servants'

Widow and Orphan Benevolent Funds". In 1906 for instance the

entertainment included "Songs of a sentimental character" such as

"Dear Heart" by Miss Kate Harper, and "The Village Blacksmith" by

Mr. Frank Thorne. Mr. Sam Cotton was assisted in his songs, monologues and sketches,

"amidst much laughter" by "Miss Gerty William's comic effusions". There

was a pension scheme of sorts provided by the company, costing the

member in later years 6d, but with no provision for his wife or children

in the event of an accident. This scheme was scrapped by the L.M.S., who

instituted their own Superannuation Fund, which provided also for the

railway man's family from 1938 onwards. The Bushbury men had their own Welfare Club which

ran an annual trip to Blackpool, the "L.M.S. Magazine" for 1938

reported that "100 members, accompanied by their wives and families,

enjoyed a well organised trip in fine weather". |

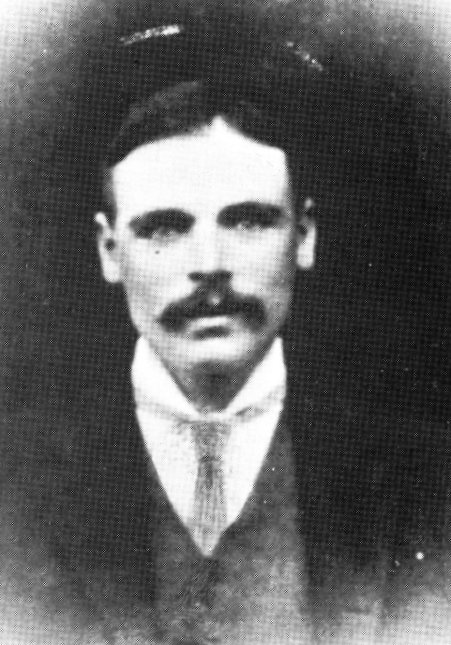

Bushbury engine driver Walter (Dick) Charman

was born in Bushbury Lane and is seen here around the turn of the

century. His brilliant blue eyes, for which he was noted, are

apparent even in the photograph, loaned from the family album of

Joyce Batchelor. |

It was the Bushbury

men who began what became a system wide preoccupation when they

instigated the "L.N.W.R. Flower and Vegetable Show" at Bushbury in

1919.

In 1922 there were 750 participants, 200 more than the

previous year, displaying their procreations under a marquee at

Oxley Manor Park Estate. Additional fun and entertainment was

provided by the perriots, competitions, sports, dancing and the

"Bescot Silver Prize Band".

There was a cricket team, who played on

an allotment near to Bushbury Junction, complete with an old railway

carriage to change in. A proper pitch was later used at Tremont

Street. Football too was played, using the excellent ground behind

the Star motor works.

The "Mutual Improvement" classes held meetings

at the old station near to the shed, with visiting lecturers

explaining the workings of the steam engine. One of the drivers made

a working wooden model of the Walschaerts valve gear, in his own

time, to help novices understand its mysteries better. |

"George the Fifth" class 4-4-0 No. 5329

"Queen Mary" stands ahead of the water tank at Bushbury Shed, circa

1929. Water for the tank came from the company's own pumping station

at Wood Lane. If the level in the tank fell low it was then

replenished from the town supply. The amount used being duly

recorded on a water meter and later charged to the company.

Photograph: Joe Hancock. |

| The Great Western, unknowingly, provided the Bushbury men with their

swimming facilities. They would creep off to Bushbury pool under cover

of darkness and use the diving board, swimming out to the raft of

barrels moored in the middle, all provided by the G.W.R. Institute at

Stafford Road! Finally the men of Bushbury made it on to the B.B.C.

Radio when listeners to "Childrens hour" heard the commentator take them

from Wolverhampton to London on a "2 hour express". Many adults must

have learned with surprise of the forgotten heroes of Bushbury who ran

the Birmingham to London expresses! These "forgotten heroes" were part of the Bushbury scene, coming and

going along Bushbury Lane with their wicker baskets containing their

"snaps", ascending and descending the stairway that led down from the

railway bridge to the shed. Until the 1950s this stairway was the only

means of entrance to the shed, and occasionally a company detective

would be waiting beside the gas lamp at the top of the stairs to search

the men as they came off their shifts.

Often the first job given a youth at the shed was that of "caller up",

when he would walk on the "short distance" turn, or ride a solid-tyred

bicycle on the "long distance", which covered an area of many miles.

From this he would progress to cleaning, working with a gang of five or

so others on one engine at a time. Red wax was kept for engines such as

'Westminster" in its crimson finish, black for the "blackberry black"

and vaseline or black oil for the smokeboxes. Two hours were allowed for

the bogies, drivers and side rods on the one side, but they had to be

clean on both sides of the wheel or side rods or you did it again. |

Bushbury Stalwarts, 1938. Those known are

as follows (left to right):

Back Row: J. Fellows, D. Wiltshire, N. Lloyd, E. Murray,

R. Cripps, S. Newill, H. Simms, R. Kerry, F. Andrews (Foreman

Cleaner), and J. Ford.

Middle Row: J. Moore, J. Sharp, N. Golding (Shed Master),

? and W. M. Burgess.

Front Row: R. Bownes, H. Jones, ? V. Haller, E. Nicholls,

J. Ballinger, and B. Hayford.

Those sitting on the front row are on wooden formers that were

used to build the brick arch in the firebox. Photograph courtesy

of J. Batchelor. |

| One of the less pleasant aspects of cleaning was the occasional suicide

or dead animal whose remains had been left splattered beneath the

engine, dried hard against the firebox. One driver on the London turn

had run down seven suicide victims in his time.

By British Railways

days, from 1956 or 1957 onwards the, cleaning went "to the wall". A boy

would be "passed cleaner" at 17 and used more often firing than

cleaning, on local turns.

There were the bar layers, Steam raisers,

washing out, all the usual engine shed activities. Washing out was

casual to say the least in L.N.W. days, with often one plug only being

removed and the others ignored. With the tightening up introduced by the

L.M.S. the job had to be done properly, but the heads of the washing out

plugs would often strip rather than unscrew they were furred in so

tightly. As Alfred Brough recalled, it was a wonder they steamed at all! |

Alfred Brough as a young man. Alf' put in

twenty years of hard work at Bushbury. Needless to say these were

not his working clothes!

Courtesy of Alfred Brough. |

| The worst jobs were fire dropping and coaling. The fire droppers would

empty the ashes from the smokebox, but the wind would cause them to

explode into flames in the man’s face. To this day Alfred Brough has no

eyelashes, which he puts down to this. The fire droppers could tell a

bad driver by the glowing smokebox and the paint blistered off part way

up the smokebox, then they knew that they were in trouble. Coaling was a shattering job, the coal wagons being emptied by hand as

piece work. The coalers could earn more money than the timekeeper or the

top link drivers, but Joe Hancock remembers the effect the work had on

them, he would see them staggering along the lane at Bushbury, holding

the railings for support. Alfred Brough recalls that his hands were so

calloused that a sixpence would fit into the cracks edge, on!

The coalers were paid 4½d per ton if the coal wagon was 4’ 2"

or under, 6d per ton if it was over that height. They would throw the coal over the top of the wagon into the tender by

guess work as they dug lower and lower into the coal (L.N.W. coal wagons

having no side doors were unloaded from the top down, a tough job.).

Bushbury engines used three grades of coal. "Dalton" being the best, for

the London expresses. The men called it "sun coal" because it would

burst instantly into flame "like the sun". |

An unknown "Experiment" class

4-6-0,

believed to be "City of Liverpool" (L.M.S. number 5460) stands

before the main shed building in the 1930s. The shed follows the

standard L.N.W.R. design, notice the open doors to the left and the

original northlight roof. In the foreground are

Foreman Cleaner

Frank Andrews and Shed Foreman Longstaff in his black bowler.

Courtesy of Joyce Batchelor/Ted Talbot. |

| "Cresswell" was used for the heavy freight engines,

and "Littleton" cobbles, the common coal. In winter the coal would

freeze together, the men would struggle shovelling the frozen

Littleton Cobbles into one engine, coal up two London engines with

Dalton and return to the Littleton coal to find it frozen solid

again!

The pay varied around £3 working mornings,

£4-10-0 working

afternoons and £5-5-0 on nights for a 48 hour week, a top driver

earned about

£4-10-0 per week. This all ended with the introduction

of the automatic coaling plant, when the coalers rates plummetted to

£2-10-0. Alf left Bushbury as the war came and found himself "in

clover" earning £5-17-0 per week immediately!

|

Bushbury shed staff take part in a tug of

war in the late 1930s. Almost every family in Bushbury had a railway

connection in those days.

Courtesy of Joyce Batchelor. |

| Inside the shed were four baulks of timber meeting

in an apex in the shed roof. Coming down from this was a hydraulic

lift worked by a steam pump in the corner. Thus a limited amount of

maintenance work could be carried out at the shed. The bogies of an

engine could be run out clear and such things as piston glands, rivetting or adjustments to the motion attended to. Boilersmiths

were on hand to seal any leaking tubes or attend to minor problems.

Brakes were adjusted constantly, the goods engines being set

somewhat slacker than the expresses. Spare parts for the repairs

came from Bescot or Crewe. The spares would arrive as a parcel at

Wolverhampton where they would be collected and taken to Bushbury on

the front of an engine. From L.M.S. days the stores kept a set of

tools, a bucket and a fireman’s shovel for each engine, but prior to

this it had been a case of grabbing what was available.

One driver known as Frank Huband carried his own piece of equipment

when working on the "Super Ds", for he was too short to reach the,

whistle, "so being a British working man, he put a piece of string on it

and worked it like that"! This compares favourably with the stay of the

little Welshman at Stafford Road who drove the "King" class expresses to

London standing on a bucket to reach the controls.

Friendly rivalry between the men of Bushbury and their ex Great Western

counterparts continued long after nationalisation. In the late 1950s the

young Bushbury cleaners would sneak into Stafford Road and dirty up an

engine, just tidied by their rivals. One young cleaner transferred from

Stafford Road to Bushbury, and when asked why, remarked with a sly grin,

"Well, if you can't beat ‘em, you may as well join ‘em!"

|

An interior view of Bushbury

shed in later days, showing the replacement roof. The roof replaced

the standard L.N.W.R. 'northlight' structure. The opportunity was

taken to raise the whole roof on blocks (clearly shown in the

picture) in anticipation of the future storage of electric

locomotives. Nothing came of this idea and the shed closed in April

1965. Photograph courtesy of Tom Booth. |

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Edition 6 |

|

Return to

the Beginning |

|

Proceed to

Stourbridge Jcn. |

|