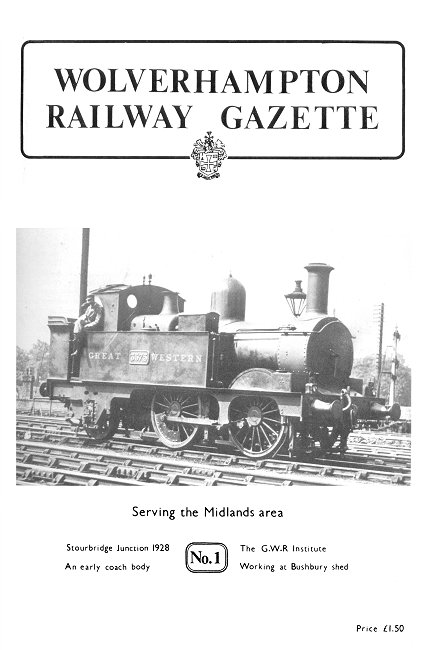

The First Edition

|

The magazine was launched in 1986 and the first edition

included articles on working at Bushbury Shed, an early coach body at

Oxley, Stourbridge Junction Station, Shrewsbury and Chester engines, the

Stafford Road Works Institute, the Low Level Station and the first part

of a compilation of principal events in Wolverhampton's railway history.

There were lots of illustrations including old photographs. Its now

interesting in hindsight, to read the article on Wolverhampton Low Level

Station, which at the time was about to be turned into a transport

museum. A project that sadly never materialised.

The cover photograph is of Great Western 3571 class,

0-4-2 tank engine, number 3575. The photograph was taken at Stourbridge

Junction. |

The G.W.R.

Institute

Social Life at Stafford Road Railway Works

| "The Institute" attached to the railway works at Stafford Road was

opened in 1855, modelled along similar lines to its older sister at

Swindon. Initially the membership stood at 140, all being men attached

to the railway works. From the beginning the railway company took an

active interest, Joseph Armstrong taking the presidents chair whenever

possible. Much of the money for such things as library books was

provided by individuals such as Sir Watkin, from within the company

itself. By 1859 the Institute library had 670 books with a monthly circulation

of 186. The reading room was supplied with 5 daily newspapers, 11 weekly

newspapers and periodicals, and 4 monthly journals. In 1858 the company

provided members with the first of what was to become an annual and ever

more popular event, when an excursion train filled with members and

their families set off for 3 days in Liverpool. In the same year a brass

band was formed, the Institute to provide the required musical

instruments, the teacher’s fees to be paid by the members themselves. At

the same time, a drawing class had begun under the expert direction of a

Mr. Bennett.

Also during 1858 the Institute council had provided an achromatic

microscope, a "large and powerful telescope", and a magic lantern.

"Stereoscopes have been placed in the reading room, and their varied

scenes have proved interesting and amusing". By 1860 chess,

draughts and a singing class had been added, and fourteen instruments

furnished for the band. A harmonium had been placed in the reading room,

a gymnasium and a "quiet" garden provided, which was well used during

the evenings that summer.

In December 1862 a new spacious building was erected, with gas lighting

laid on, at a cost of £100. This handsome structure lasted until the end

of the Stafford Road works in the 1960s. 800 people sat down to the

opening concert, frowned down upon by the life sized busts of Brunel and

Gooch, the walls being decorated with pictures showing the development

of the steam locomotive. Mr. Joseph Armstrong alluded to the wall

mounted locomotive views in his opening address, acknowledging Mr.

George Stephenson’s prowess in the spheres of engine design but adding

piously that the same gentleman was responsible for desecrating the

sabbath, running trains on Sundays. Everyone else had followed on from

his bad example being the moral of the story.

The next great occasion was the Royal marriage in

1863, when the Institute building flew flags of England, Denmark and

France from its flagstaffs, Mr. Fewtrill fired his cannon and 250

workmen sat down to a dinner at 1.00 p.m. inside the Institute.

Water only was provided "to meet the wishes of a number of workmen

who are advocates of the principal of total abstinence". After an

afternoon at the racecourse where festivities were laid on, the men

and their families enjoyed a tea and a ball, which did not break up

until after midnight. Mr. William Dean, then living in Alexandra

Road, Wolverhampton, gave the opening address, the newly formed

Institute Choral Society providing the music. By 1866, a bagatelle

room, had been added, and a "collection of microscopic objects".

Regular social functions had been instigated from the start, with

about five concerts occurring each year, and weekly meetings of the

various societies, the building being open each working day.

|

|

The entrance to the G.W.R. Institute as it

appeared on 20th January 1932, erected on the site of the former

toll house on the Stafford Road. The low bridge seen to the right

was replaced by a higher structure the following year, allowing the

double decker trolley buses a through passage. |

| By 1871 there was a "Mechanics Association", a cricket club and

fortnightly rather than monthly entertainments. In 1875 a large billiard

table was purchased and a recreation ground levelled and prepared in a

field lying between the canal and the branch railway leading from

Cannock Road Junction to Bushbury. Here a cricket pitch and a gymnasium

boasting "horizontal, parallel and leaping bars, double and single

trapeze, climbing poles and ladder swings etc." was erected. At one end

of the field a quantity of fish were put into the recently made Great

Western reservoir "so that angling may constitute a portion of the

recreation". A newly constituted band, complete with a distinctive

uniform was formed in 1876 and held a brass band competition at the

beautifully wooded grounds of Oxley Manor. Crowds of people lined the

Stafford Road to see the event and a jolly time was had by all, thanks

to the benevolence of the owner of land, the M.P. Alexander Staveley

Hill. After the prize giving, won by the "Kidsgrove Real

Excelsior Band" the entertainments went on into the evening with "Old

English pastimes", and dancing. |

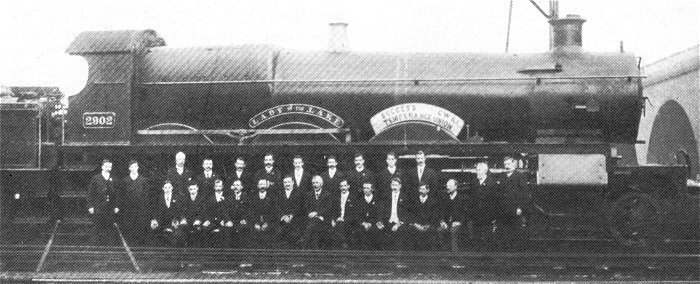

The officers and committee of the

Wolverhampton No. 1 branch of the G.W.R. Temperance Union in 1909.

In the background is number 7902 "Lady of the Lake" which hauled the

first non-stop train over the new Birmingham route. Photo: G.W.R.

Magazine. |

| In 1881 the membership stood at 870 but by 1885 the

membership was falling, the recreation ground had been given up, the

billiard and bagatelle room closed. The Junior Engineering Society

held talks on subjects such as "Joys valve gear as applied to Great

Eastern express engines". The Railway Servants Mission, presided

over by the L.N.W.R. stationmaster, Mr. Worth, held the excursions

for railway employees and their families were described by 1897 as

Wolverhampton’s largest excursion of the year". The trains started out from Low Level but most people joined them at

the newly opened Dunstall Park station. Over 2000 people took advantage

of the company trains to Birkenhead, Liverpool, North Wales, Manchester,

Worcester, Malvern and the Severn Valley line, Newport, Cardiff,

Swansea, Bristol, Western-Super-Mare, London and intermediate stations,

a far cry from that first trip in 1858! There were missions and tea

evenings which were attended by 100 men and their wives, but the

original enthusiasm seems to have dwindled. |

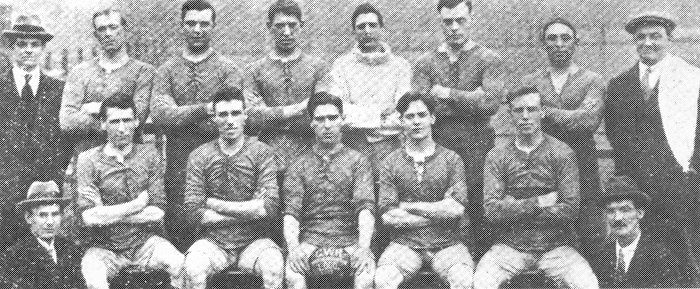

Stafford Road works football team from the

pages of the G.W.R. magazine. The club was started by the works

manager Charles Crump as early as 1876. When the team played the

"Walsall Swifts" at Foxes Lane in 1879 before a crowd of 2,000, the

Swifts complained that spectators had lined the goal area,

preventing the ball from scoring! Crump maintained an interest in

the club for the rest of his days. The team are shown here in the

1920s. Photo: G.W.R. Magazine. |

| In 1890, the Great Western Temperance Union began to

meet at the Institute, as did the Locomotive Steam Engineman’s

Improvement Class. The membership of the Temperance Union by 1895

stood at 1047 compared to 800 in the previous year, and at

Wolverhampton a Band of Hope was in a flourishing condition at the

Institute. A singing class was formed, and the Great Western Mission

set out from Stafford Road regularly with their accordion to visit

the lodging houses of the town.

Membership of the Institute fell in 190l due to 23 of its members

leaving for the war in Africa. The total of books in the library stood at 3,856, having remained at

this level for some years previously. Newspapers and periodicals were

still provided, the reading room was used for Sunday and week day

services by the Temperance Union and the Railway Mission, the Band of

Hope and Choral Union meetings using the room on Thursday evenings. This

obsession with sour faced Victorian religion seems to have had the

effect of driving many functions to more amiable surroundings. For

instance the Great Western Social evening in 1904 was held at the "Angel

Hotel" and attended by a "large number of the company's officials,

clerks, foremen, etc." Even J.A. Robinson himself attended! The new

century was bringing a wind of change in other ways too. |

A view of the vehicular entrance to the

Stafford Road Works, with the Institute on the right, soon after

closure. The terraced houses, home to so many railwaymen, are also

empty and awaiting demolition.

Photograph John Bates. |

| At least one member of the Great Western Mission

abandoned the sing songs in the lodging houses, and the attempts to

raise the spiritual aspirations of the down and out. A.P. Mitchell

began to wonder if the cause of the problems could be tackled

instead, and joined the newly emerging Labour Party. Membership of

the Institute still stood at 1,102 in 1910 when "many worn out works

in the lending library have been replaced, as far as practicable, by

new copies". Billiard and Whist drives have been well attended. The

bowling played 26 matches and fishing competitions were held at

Bushbury Pool. For the second year in succession, gardening competitions had to be

abandoned owing to lack of entries, and neither boating nor swimming

found much favour. "A football club has been started, the first team

being affiliated to the Wolverhampton Friendly League". Activities at

the Institute ceased to find space in the newspapers from the First War

onwards, and by 1922 when the Great Western Temperance Union held its

annual meeting at Wolverhampton, thousands from all over the system

heard the speaker denounce the men of Wolverhampton for having so few as

176 abstainers in their ranks. The Institute still had an Orchestral

Society though, for they provided the music for the evenings

entertainment.

From the 1920s onwards the upsurge in other amusements, the cinema, the

radio, the dance halls took their toll of the working men’s

institutions, which were essentially a Victorian commodity. The football

club continued, appearing several times in the "Great Western Magazine",

the swimming pool at Showell Road remained popular, but the Institute

itself played less and less of a role in the lives of the men at the

works. The billiard room remained in use to the 1960s, the smaller rooms

were used for union meetings, but life had passed the Institute by. The

building was closed and demolished along with the works, which it had

served for over a hundred years. A section of the steep stairway that

once led up to the entrance is all that can be seen of the Institute

today.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Return to

the Beginning |

|

Return to

the Exhibition |

|

Proceed to

Edition 2 |

|