|

What follows is a description of

Tettenhall that was published in October 1904 in “The

Wolverhampton Journal”, a monthly magazine published by

Whitehead Brothers, St. John’s Square, and King Street,

Wolverhampton.

The article, written by local

historian James P. Jones includes the early history of

Tettenhall, and the history of the Wrottesley family who

lived in Wrottesley Hall. The photographs were taken by

James P. Jones, who also owned the engraving. The

section about the Wrottesleys is both interesting and

informative. It describes the family’s struggles, and

involvement in many wars. I have included the original

illustrations, and a few adverts from the magazine.

Bev

Parker |

|

Few busy towns of the size and

importance of the "Metropolis of the Black Country," can

boast of such a wealth of charming rural villages in

close proximity as does Wolverhampton. Strangers who are

carried through the town by the various railways have

the impression that the town and district are equally

"black." Those more fortunate, who stay, are delighted

with the picturesque country they discover. The

transition from town to country is so sudden, the

discovery so unexpected, that the beholder is

inexpressibly charmed and finds that which gives

pleasure to the eye and relief to the mind.

Few English villages possess a more

picturesque locality than Tettenhall, which is prettily

situated on the slope of an abrupt hill, rising above

the valley of the Smestow. This cliff, which terminates

in a large plateau at Tettenhall Wood, forms a natural

barrier between town and country.

The scenic beauties of the village

are undeniable, it is a haven of rest after the heat and

burden of the day, and its freshness and charm are

enjoyed and shared alike by the toiler and dweller in

the slums of Wolverhampton and the civic magnates who

have made it their home. Its peaceful charm led an

enthusiastic admirer to pen a few lines on "The

beautiful village of Tettenhall," his poetical effusion

closes with the following rapturous eulogy:

|

Tettenhall, thy still engaging scenes

conspire

To wake the, sages and the poets fire,

From noisy town, with worldly cares replete

To ease the mind; lo! this the choice

retreat

Here Hampton's sons in vacant hours repair

Taste rural joys, and breathe a purer air. |

These lines, though written a

century ago, do not today exaggerate its charms of

peaceful beauty. |

Tettenhall Church (south west view).

|

The history of the village is

attractive and interesting, for it can boast of a

greater antiquity than many English villages. It is

first mentioned in history 150 years before the date of

the Norman Conquest. The Anglo Saxon Chronicle under

date A.D. 910 says: This year the army of the Danes and

the Angles fought at Totanheale on the eighth of the

Ides of August (6th August) and the Angles obtained the

victory.

There are other versions of the

battle recorded by the various monkish chroniclers, but

all agree that it took place at Tettenhall,

Staffordshire. Collating the evidences which are extant

I am forced to the conclusion that two battles were

fought in this district A.D. 910-911.

The records show that a Danish

force landing on the East coast, came down the River

Trent and sacked Lichfield, while it is proved that

another Danish force came up the Severn as far as

Bridgnorth. These two forces effected a junction at

Wednesfield, where they were defeated, and falling back

upon Tettenhall were caught between the armies of the

West Saxons and the Mercians and totally defeated. There

is no doubt the battle was fought along the valley of

the Smestow and ranged from Autherley to beyond

Wightwick. The Danes after their defeat at Wednesfield

would naturally fall back upon Tettenhall, as the

position is just such a one as a retreating force would

take up. They probably found that the commanding ridge

at Tettenhall was occupied by the West Saxons, and so

caught between the two armies their defeat was certain.

The presence of some large tumuli

at Wightwick indicate the burial place of the slain, as

well as the site of the battlefield. Some years ago I

obtained permission from the late Colonel Henry

Loveridge to explore the largest tumulus, but owing to

the lack of funds, and worse still, an entire lack of

interest in archaeology locally, the project had to be

abandoned. I have always regretted the failure, as I am

convinced the results would have been of considerable

value, not only to Tettenhall, but to the county of

Stafford. |

|

The parish of Tettenhall, in area,

as distinct from the village, is considerable. It

measures in length 7½ miles, while its greatest breadth

is nearly 4½ miles. Within its boundary are included

Tettenhall Regis, Tettenhall Clericorum, Perton,

Wrottesley, Pendeford, Wightwick, Compton, Bilbrook,

Aldersley, Barnhurst, Trescott, and the Wergs. Of these

the first eight names appear in the Domesday Book, A.D.

1086.

At the date of the great survey of

England in A.D. 1086, Tettenhall was almost entirely

forest and woodlands, what are now main roads and

byeways were then simply trackways made through the

woods from one settlement to another, but, as the

country became more populated, fresh settlements were

made, and communication between places widely distant

became easier; clearings were made in the forest and the

trackways were widened into passable roads.

These clearings formed the centres

of the village life, and usually consisted of the church

and priest's house, the manor house within the demesne

lands, and next in importance the village mill, usually

placed on the banks of a stream in order to use its

water power. Grouped around these were the homesteads

and cottages of the tenants, most of whom inhabited the

principal street or road in the village, called Lower

Street.

In all villages with any claim to

antiquity, interest is more or less centred on the

church. Tettenhall church is built upon a gentle

acclivity rising from the Smestow Brook where "bosom’d

high in tufted trees" it overlooks the village green and

street, and seems to breathe a spirit of quiet

guardianship over its peaceful graveyard, where so many

of the village fathers sleep. Nearby, some ancient yew

trees, believed to be coeval with the Church, form a

sombre background to the eastward sloping graveyard,

brightened by promise of early dawn.

From the summit of the cliff above

the Church an extensive panorama is obtained of the

surrounding country for many miles. Looking to the East

a fine view is obtained of Cannock Chase, the borders of

which touched Tettenhall parish. Further South is to be

seen the town of Wolverhampton with its forest of tall

chimneys breaking the skyline. To the South West will he

seen Sedgley Beacon, Penn and Wombourne; farther West

still lies the village of Pattingham, with the horizon

bounded by the deep purple of the Wrekin and Clee Hills.

The history of the fine old Church

is as equally interesting as that of the village. It was

founded by King Edgar, and was a collegiate church with

a dean and five prebendaries as early as A.D. 960. No

traces of the early Saxon church exist, but the Norman

church which sprang into being later was built upon its

site. This in turn gave place to a later church, which

forms the greater part of the present edifice. The most

interesting portions of the present building are the

nave, chancel, north aisle, the tower, and south

clerestory. The Pendeford Chapel has a fine lancet

window, but the gem of the building is the east window

with its curious arcade of slender columns, a pure

example of early English work, probable date, 1207. |

Wrottesley Hall, built 1696, destroyed by

fire, 16th December, 1897.

|

In front of the Wrottesley Chapel

the beautiful oak screen of fine perpendicular work is a

feature of the building, while the private chapel of the

Wrottesley family contains some very fine monuments,

particularly an alabaster slab with a gracefully drawn

effigy of Richard Wrottesley and his wife, A.D. 1521.

The village greens at Tettenhall are among its most

prominent features; here in olden times rude sports were

indulged in, and at the annual wake, the Lower Green was

usually a small reproduction Wolverhampton fair.

In the days when bull baiting and

other sports of a similarly degrading character formed

the chief amusement of the people, it is recorded that

some enterprising men from Wolverhampton came to

Tettenhall and stole the bull, thereby spoiling the

sport of the Tettenhall men.

In the still more distant and

lawless times of the Middle Ages, even the Church was

powerless to cope with the lawlessness which prevailed,

for it is recorded that one man killed another before

the door of Ralph, the Canon of Tettenhall; while at the

Wergs a band of mercenaries attacked a cottage, killed

the husband, burnt his cottage, and threw his child on

the dungheap! Excommunication was the most powerful

weapon of the Medieval Church, but even this extreme

course had but slight effect.

There was at Wrottesley a letter

from Sir John Notyngham, Dean of the King's Chapel at

Tettenhall, to the chaplains of Tettenhall and Codsall,

ordering them to excommunicate certain persons for

stealing wheat and beans out of their neighbour’s barn

or field, unless they gave satisfaction.

It appears that Adam Taylor, a

tenant of the Dean's Manor at Bilbrook, had been robbed

of eleven sheaves of wheat and six sheaves of beans, and

that suspicion of the theft had fallen upon his

neighbours, William Colett and his son John and his

daughter Margery, and these last, suffering under the

imputation of theft, had appealed to the Dean for

protection. It seems an absurd thing to excommunicate

nameless persons, but the letter probably had the effect

of stopping the defamation of the character of the

accused. It is a curious relic of the power of the

Medieval Church, and the following is a translation:

The Comissary of your venerable

lord John Notyngham, Dean of the King's Chapel of

Tetenhale to the chaplains of the parishes of Tetenhale

and Codeshale, Greeting in the Author of Salvation.

We have received the grave

complaint of William Colett of Brydbrok (Bilbrook) and

of John his son and Margery his daughter, to the effect

that certain sons of iniquity, of whose names they are

entirely ignorant, had wickedly and maliciously defamed

the said William, John, and Margery, respecting goods

and .... that the said William, John, and Margery had

carried away eleven sheaves of wheat and six sheaves of

beans from the grange or field of Adam Tayleur their

neighbour, against the will of the same.

We therefore command you by

virtue of your obedience, firmly enjoining you, after

the third monition from the day of the receipt of this,

and within fifteen days, to excommunicate al1 and

singular defamers of this nature with the ringing of the

bel1, candle lighted and extinguished, and cross and

banner held erect in hand, unless they give testimony

respecting the premises and until … but then be cited

nevertheless so that they may appear before us in the

Church Tetenhale at the next following Chapter ....

those things which the said John William and Margery may

legitimately bring against them to do or receive ....

testimony of which the present seal of our office is

appended to these presents. Dated at Wolverhampton, the

Wednesday after the Feast of St. Martin the Bishop and

Confessor, 1387.

In the original, some of the words had become so

faint that it was impossible to make them out, but there

was sufficient left to enable the meaning of every

sentence to be gathered. This document was destroyed in

the great fire at Wrottesley Hall in 1897, and the above

copy is the only one in existence. |

Tettenhall Church, with a distant view of

Wolverhampton.

|

Among other interesting historical

features in the village, the Barnhurst must not be

omitted. It is the ancient home of the Cresswells.

Formerly the tithe barn of the Cannons of Tettenhall, it

was sold to the Wrottesley family, from them it passed

by purchase to the Leveson family, ancestors of the

Dukes of Sutherland, and was then sold to the Cresswell

family, who were merchants of the Staple in

Wolverhampton.

The Cresswells are of very ancient

descent, and helped to found what in later years became

a great market in Wolverhampton; even now, long after

the market has died out, traces of it survive in the

names of the various folds of the town, such as Townwell

Fold, Wheelers Fold, Farmer's Fold, etc.

A member of this family married

Joan, the daughter of John Dyott, Esq., of Lichfield, a

monument to whose memory is still preserved on the north

wall of the chancel in Tettenhall Church. She was a

relative of the famous "Dumb Dyott" of Lichfield, the

Royalist who shot Lord Brooke, during the siege of that

city in 1643 by the Parliamentary Army.

The remains of the old Manor House

at the Barnhurst consist of a gateway tower, some

portion of the moat, and the ancient columbarium or

dovecote, this latter, a rare privilege granted to lords

of manors. The tower is a finely preserved remnant of

early Tudor architecture, and although not now used as a

dwelling house, is a valuable relic of domestic

architecture. The dovecote, octagonal in shape, is in

excellent preservation and has provision for some

hundreds of birds. The Barnhurst estate was purchased

the Corporation of Wolverhampton about 1872-3, who now

utilize it as a Sewage Farm.

The present representative of the

Cresswell family is Sackville Cresswell, Esq., of Hole

Park, Rolvenden, Kent. The hamlet of Perton is

frequently mentioned in history, and was given to the

Abbot of St. Peter's, Westminster, by King Edward the

Confessor. This grant is still preserved in the Record

Office; the following is a translation:

Eadwarcl King greets Leofwine

Bishop and Eadwine earl and all my thanes in

Staffordshire friendly; and I tell you that I have given

to Christ and St. Peter at Westminster the land at

Pertune and all the things that thereinto belong in

woods and fields; with sac and socne, as full and as

free as it stood to myself in hand, in all things, to

feed the abbot and the brotherhood that dwell within the

Minster; and I will not permit any man to oust any of

the things that thereinto belong.

God preserve you all.

The Bishop Leofwine, mentioned, was

the last Saxon Bishop of Lichfield, and the first Abbot

of Coventry. From his death, in 1066, until 1836, no

other bishop took title only from Lichfield, but held

the dual title of Lichfield and Coventry.

Perton during the Middle Ages was

the battle ground of the rival families of Perton and

Wrottesley. Owing to a disputed ownership of land in the

Manor of Perton, a family feud had long existed between

them, which finally culminated in the death of John de

Perton by Sir Hugh de Wrottesley, K.G., in an affray

near Tettenhall. In after years, owing to the Perton

family becoming extinct, the estate passed into other

hands and was finally bought by the Wrottesley family,

the present owners.

Perton can also boast of being the

birthplace of a man who became Lord Mayor of London in

A.D. 1644. It would be difficult to find in the annals

of any municipality a more romantic history than that of

Sir John Wollaston, who began life as a farmer’s son at

Perton and ended as Lord Mayor of London. His name is

perpetuated by the following bequests, To the poor of

Tettenhall, Co. Stafford, where I was born, £5 and

Whereas my uncle, Henry Wollaston, of London, draper,

hath formerly given fifty two shillings per annum to the

poor of Tettenhall aforesaid, I now make up the sum to

£10 per annum.

For many years before the

disastrous fire on December 6th, 1897, which destroyed

the mansion and the priceless treasures preserved here,

Wrottesley Hall from its commanding position on the

summit of a thickly wooded slope, was a conspicuous

object from many points of view in the village, it was

the last of a series of houses extending over a period

of seven centuries. |

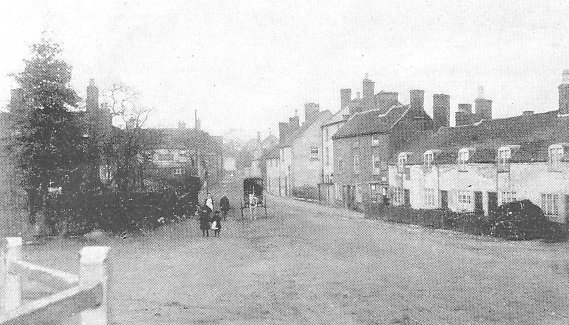

Lower Street, Tettenhall.

|

The Wrottesley family has been

identified with the village of Tettenhall for many

centuries and has owned the estate from A.D. 1160. The

history of the family is of great interest, and many of

the present Lord Wrottesley's ancestors played a

prominent part in the making of the history of England.

In the long struggle between King

Henry II and the Barons, led by Simon de Montfort, in

A.D. 1260 to 1268 Hugh de Wrottesley adhered to the

party of Simon, and was present at the Battle of Evesham

in August, 1265. As a result he was a fugitive and was

disinherited of his estates. But in 1267 Parliament

passed an award, known as the "Award of Kenilworth," by

which all those who had taken arms against the King and

had been disinherited, could receive back their estates

on payment of a fine equal from one to seven years'

income, according to the degree of their guilt.

Hugh de Wrottesley paid a heavy

price to regain his estates, for he was fined 60 marks,

equivalent in modern money to £3,000. On the 10th of

May, 1300, William de Wrottesley and two other

Staffordshire knights, were appointed by letters patent,

justices, for the due observation of the articles

contained in the Great Charter and the Statute of

Winchester, in the county of Stafford, and to hear and

determine plaints thereon. In this way William de

Wrottesley became associated with one of the great

landmarks of English Constitutional history.

On 22nd May, 1306, there was

instituted the famous Order of the Bath, and William de

Wrottesley's eldest son William, was knighted with great

solemnity before the high altar at Westminster, with

Edward, Prince of Wales, and 267 others, the eldest sons

of earls, barons, and knights. Of these, sixteen were

eldest sons of other Staffordshire families. This

William de Wrottesley was the father of the most famous

of all the Wrottesley's, Sir Hugh de Wrottesley, K.G.

I can only briefly sketch the

career of this remarkable man, who by his prowess and

skill in arms played an important part in the warlike

reign of Edward III. He was educated in the Abbey of

Evesham, and gave early promise of that brilliant career

which placed him on the highest pinnacle of chivalry,

for it is remarkable that he was a knight and in

possession of his estates when only twenty years of age.

He had won his spurs on the field of battle, and was one

of those knighted by the King in Scotland in A.D. 1333,

on the eve of the Battle of Hallidoun Hill.

In 1334 Sir Hugh was making

preparation to join the Crusade under Philip de Valois

the French King, and King's Letters of Attorney for

three years were granted to him whilst on a pilgrimage

to the Holy Land. The departure of the Crusaders was

fixed for the Spring, 1334, and was afterwards postponed

to 1336, but the hostilities which broke out between

France and England prevented the execution of the

design. Just about this time some suits of law in which

Sir Hugh was involved, afford a glimpse of the family

feud between the Wrottesleys and the Pertons, lords of

the neighbouring manor.

The dispute appears to have arisen

over the ownership of some land which had been given as

the marriage dowry of a daughter of the Pertons who had

married a Wrottesley; and the Perton family were suing

Sir Hugh for its recovery. Numerous suits at law were

instituted by the Perton family against Sir Hugh de Wrottesley and his tenants for trespass and assault,

until it became unsafe for either party to go abroad

unless they were attended by a considerable retinue of

servants.

Sir Hugh had been absent fighting

for the King in Scotland, and during one of his visits

home to Wrottesley, he with a party of his servants had

met John de Perton, and some of his friends at

Tettenhall, where the two parties came quickly into

collision, with the result that John de Perton was so

severely wounded that he died a few days later.

Sir Hugh de Wrottesley and his

friends were arrested and put in prison at the

Marshalsea, Kingston-on-Thames. The Marshal of the Court

at this time was the famous Sir Walter de Manny, who

being a friend of Sir Hugh, connived at the escape from

prison of Sir Hugh and his friends, who went with the

Marshal to France. For this offence the Perton family,

through the influence of the Chief Justice, obtained a

sentence of outlawry against Sir Hugh.

While abroad, however, Sir Hugh's

prowess won such favour with the King that he obtained a

full pardon for all offences committed by him. In spite

of this, on his return to the country, the sentence of

outlawry was enforced, and he and his friends were cast

into prison again, and brought before the Chief Justice,

Sir William de Shareshull, of Patshull.

Sir Hugh and his friends were now

in great peril, for by a recent enactment they had lost

their right to a trial by jury, and could be sentenced

to death without further trial. These proceedings

contrast so strongly with the usual dilatory procedure

of the Law Courts, as to suggest animus on the part of

the Chief Justice, who was connected by marriage with

the Perton family. Luckily for Sir Hugh, he was able to

produce in Court the King's pardon, and so frustrate the

conspiracy against him. To meet his expenses for the

expedition to France, Sir Hugh had mortgaged part of his

estates, and a daring exploit recorded of him is equally

illustrative of his bravery, and his enterprise in

obtaining a ransom to pay off this mortgage.

It seems that while in France, Sir

Hugh taking with him a party of armed men from the

English Army, made a sudden raid upon the French Camp,

and captured as prisoners, Ralph de Montfort and other

nobles, and with the ransom he obtained from them paid

off the debt on his estates. While in France he also

received a Charter from the King to make a Park at

Wrottesley. The Charter is dated 23rd November, 1347.

Two years later on St. George's Day, 23rd April, 1349,

was founded the famous Order of the Garter. The original

Companions numbered 26, including the King and his son,

12 knights on the King's side, and 12 on the Prince's

side. Amongst whom appears the name of Sir Hugh de

Wrottesley, whose banner now hangs in St. George's

Chapel, Windsor, amongst the banners of the original

Knights of the Garter.

Sir Hugh afterwards spent several

years in France, serving under King Edward III. and the

Black Prince, and died early in 1381 in the 67th year of

his age. |

|

The next member of the family who

distinguished himself was Sir Walter Wrottesley who was

head of his house from A.D. 1464 to 1473. He was made

Sheriff of Staffordshire in 1460, by Edward IV, and was

knighted the same year.

The year before had marked the

beginning of that long and bitter strife, known as the

"Wars of the Roses," and Sir Walter was a close follower

of the fortunes of Richard, Earl of Warwick, the famous

Kingmaker. From the Earl he received many honours, and

was appointed Sheriff of Glamorgan, and was at Cardiff

in 1464. When the Earl of Warwick decided to restore

King Henry VI to the throne in 1470, he appointed Sir

Walter Wrottesley, Governor of Calais Castle. In April

of the following year, the Battle of Barnet was fought

and the Earl of Warwick killed.

On hearing of the death of the

Earl, and the complete defeat of the Lancastrian cause,

Sir Walter made the best terms he could for himself, and

the garrison at Calais. He obtained a free pardon for

himself and his friends, and regained his estates. He

died in London two years latter and was buried in the

Grey Friars Church. The next event of any importance is

the purchase of the Collegiate Church of Tettenhall with

all the spiritual and temporal rights, by Walter

Wrottesley, Esq., in 3rd Edward VI, 1550. By this

purchase, Walter Wrottesley and his successors became

Secular Deans of Tettenhall and as it was a Royal

Peculiar, exempt from all Episcopal supervision, the

wills of the parishioners were proved and registered in

his Manor Court for many generation's afterwards, until

the abolition of the Peculiars in the early part of last

century.

In 1642 the country was convulsed

by the disputes between the King and Parliament, and

both sides endeavoured to secure the support of Walter

Wrottesley, the then head of the family. The Earl of

Essex, who had been appointed Lieutenant of

Staffordshire, by the Parliament, appointed Walter

Wrottesley, Deputy Lieutenant, but he declined the

honour, for shortly before, he had been created a

Baronet by the King at Shrewsbury, on 22nd September,

1642. There is no doubt his personal sympathies were

enlisted very strongly on the King’s side, for on the

5th January, 1643, he sent to Shrewsbury nearly the

whole of his plate to be melted down and coined for the

King's use.

In spite of this Sir Walter seems

to have changed his mind afterwards, and determined to

maintain a neutral position in the Civil War. He refused

to obey the imprests made upon him by Colonel Leveson,

for the King's garrison at Dudley Castle, and a

detachment of this garrison sallying out, carried off

all his cattle, and burnt his granaries and barns, which

were outside the defences of Wrottesley. He estimated

his losses from this cause at £2,000.

In his Composition paper, he

describes Wrottesley as very strong and moated, and that

he had taken into his house several of his tenant's sons

and neighbours to form a garrison, for as he says he

stood on his guard, there was so much plundering.

At the close of 1645, the King's

cause was hopeless, and Sir Walter Wrottesley

surrendered to the Parliamentary Forces. A troop of

horse, and a company of foot were sent to occupy

Wrottesley, and it must have formed a very respectable

military post at this period. The same martial spirit

which is such a marked characteristic of the Wrottesley

family is exhibited in Sir John Wrottesley who served

with distinction with the Guards during the American

War, and subsequently attained the rank of Major

General. He was also Equerry to Edward, Duke of York.

His son, also Sir John, was M.P.

for Staffordshire in several parliaments, and served

with the 16th Lancers in Holland, and France, under the

Duke of York. He was raised to the Peerage in 1838, and

was grandfather of the present Peer. Shortly before

midnight on the 16th December, 1897, it was discovered

that a fire had broken out in Lord Wrottesley's dressing

room at the Hall. It was found impossible to locate the

source of the fire, and in spite of the heroic attempts

of those on the spot it was soon realized that the

mansion was doomed. The plate and most of the more

valuable pictures and heirlooms were saved, but the

valuable library, and the contents of the muniment room,

with its unique collection of deeds and historical

manuscripts were entirely destroyed.

The old engraving of Tettenhall

Church, with a distant view of Wolverhampton, A.D. 1796,

is interesting as showing the great changes made in

Wolverhampton during the last hundred years. At that

time, only two churches could be seen, i.e., St.

Peter's, and the "New Church," St. John's. The smoke

from the building in the centre of the picture indicates

the site of the "Old Hall," now, occupied by the New

Free Library. What a contrast the same view presents

today! Without the aid of this old engraving, it would

be difficult to imagine that the densely populated

district between Tettenhall and the town was once green

fields and gardens. |

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|