Prologue

At

1.10pm, on a bitterly cold November day in 1866, a special train

arrived at Wolverhampton Low Level Station, which had been specially

decorated by the Wolverhampton builder Lovatt with the help of the

local architect Mr. Veall. The train carried Her Majesty Queen

Victoria together with assorted attendants; the occasion for the

visit was the unveiling of the equestrian statue in Queen Square, to

the late and much lamented Albert the Prince Consort. This was in

fact the Queen’s second visit to the town: she and Prince Albert had

paused at Wolverhampton to receive a loyal address whilst en route

for Scotland in 1851.

The

Queen’s arrival had thrown the town into consternation, for her

Majesty had already turned down similar invitations from Manchester

and Liverpool. It seems that the widows of Wolverhampton had sent

her a letter of sympathy after the Prince’s death, which moved her

so much that she declared: “If ever I go out again, my first public

appearance shall be in Wolverhampton, for the love and sympathy of

the widows have comforted me in my darkest hour”.1

As it

was, her acceptance caused something approaching panic in the

organisers, as there were only eight days between the Queen’s

acceptance and her arrival to unveil the statue.

|

|

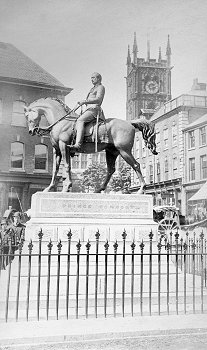

The statue of Prince Albert. |

The council

divided itself into committees to organise the ornamentation of

public buildings in the town. The noted local architect Bidlake

undertook many of the decorations at his own expense. Flags and

banners were hung across the streets and people hung banners out

of their windows. High Green (Queen Square) was decorated with

banners that ranged from the simple: “God Bless the Queen”, to

the tortuous: “The Silent Father of Our Kings to Be”. The main

streets were decorated with flags and garlands of flowers; flags

and buntings hung from all the town centre buildings. Near to

the railway station at which the Queen would arrive, there was

erected a great arch made from lumps of coal and bars of iron.

One of the pieces of coal weighed four tons and was decorated

with picks and shovels, the whole designed to show the source of

the area’s wealth. There were more triumphal arches that left

the coal arch looking a model of restraint. School Street had an

arch covered with items of hardware made in the town; iron

tubing, edge tools, domestic goods and japanned ware. The route

from the station to the unveiling place extended four miles. |

|

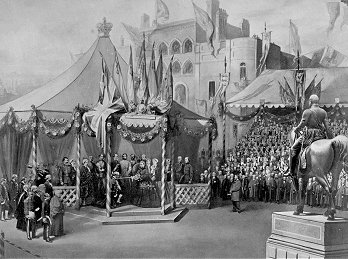

Accompanying the Queen was Lord Derby the Prime Minister and

observant people also noted the bearded figure of John Brown,

the Queen’s Scottish companion, sitting in the Dickie seat of

the Royal landau. For the unveiling itself a pavilion had been

erected with crimson draping topped with a crown and decorated

with roses; in it sat 2,000 ticket holders to watch the

ceremony. The Royal party reached the square at 1.40pm. “Her

Majesty advanced and bowed again and again…with a gratified look

that could leave no doubt how highly she appreciated the

reception awarded to her”.2 |

| When the

statue was unveiled, with the sculptor Thorneycroft himself

pulling the cord, “the expression on Her Majesty’s countenance,

as the excellent likeness of the Prince came into view, betrayed

her emotion”. The Queen walked around the statue and thanked

Thorneycroft, talked to the assembled worthies and got back into

her carriage. In the evening a Mayoral banquet was held in the

Exchange. On the whole the day went well, except for the man

charged to fire a salute from a cannon in West Park who blew his

hand off in the process. He was later awarded a pension of £20

per year. |

The Mayor, John Morris being knighted by

the Queen. |

|

Nationally, many saw the visit as unsuitable with London and

Manchester expressing indignation that Her Majesty, having been in

retirement from public life for five years, should choose

Wolverhampton, a town in the Black Country, to make her public

re-appearance. There was outrage in the capital’s press and Punch

added its two pennyworth with a particularly nasty and insulting

verse:-

|

The Queen in

the Black Country

Gracious Queen Victoria,

Wolverhampton greets you,

Franks her unlovely face in smiles with homage as she greets

you,

Underneath her arch of coal loyally entreats you;

Wreathes nails, locks, and bolts, and near the iron trophy

seats you.

Grimy labour washes and puts on its Sunday clothes,

For holiday unwonted forges cool and smithies close,

Pale, toil-stunted children leave their nailing for the

shows,

The pale strain subterranean work idly above ground flows.

In honour of the Queen, whose very name seems strange and

odd

To many here, who know no more of a Queen than a God,

Slaving from dawn to darkness at nail hammer and nail rod,

Their backs bowed to the anvil and their souls chained to

the clod |

The affair was soon largely

forgotten but the memory of the Queen’s visit remained in people’s

minds for many years, though the statue that she had unveiled very

soon became a mess due to the atmospheric pollution. The visit

though sums up much of 19th century Wolverhampton; proud, wealthy,

perhaps slightly vulgar but above all vigorous.

* Any reader of broadsheet

newspapers may feel that the attitude of those in the south-east

remains unchanged to this day.

Notes:

| 1. |

W.H.

Jones, "The Story of Municipal Life in Wolverhampton", 1903.

p.125. |

| 2. |

The

Royal Visit to Wolverhampton", pub. Edward Roden, 1867.

Anyone interested in finding out more about the Royal visit

should visit Bantock House, which has an interesting

collection of commemorative memorabilia. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Return to the

introduction |

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to

19th Century Britain |

|