|

Walsall is usually remembered as the

centre of an extensive leatherworking industry, but in

reality there was much more. It used to be known as ‘The

town of a hundred trades’, which included all kinds of

metalworking, tube making, iron and brass founding,

electrical engineering, car and motor

scooter making, chain making, lock making, and much more.

Walsall became a wealthy Black Country

town because of its many industries that flourished, thanks

to the hard-working, and skilled labour force. At the

beginning of the 19th century the principal trades in the

town were as follows:

awl blade makers

buckle makers

bradoon makers

bridle bit makers

bit makers

bone and ivory turners

brush makers

brass coach founders

bridle cutters

bridle and harness tongue makers

carpenters’ tool makers

coopers’ tool makers

curb makers

curriers

coach bit makers |

|

coach harness makers

iron founders

dog chain makers

factors

locksmiths

nail makers

platers

saddler’s ironmongers

spur makers

spur rowel makers

stirrup makers

snaffle

makers

saddle tree makers

set makers. |

|

| |

|

| In 1864 William Franklin wrote a paper about

Walsall's trades as part of a government report.

Read

his paper

|

|

| |

|

Leather Trades

The industry started from small

beginnings in the early 19th century. The 1801 census lists

the occupations of the heads of households, and acts as a

rough guide to the number of people employed in the

industry. The following list is based on the information in

the census:

|

Trade

Bridle cutters

Coach harness makers

Curriers

Glove makers

Saddlers

Tanners

Thong makers

Whip makers

Total |

|

Number of

people employed

18

5

12

1

4

2

3

1

46 |

|

The number of people employed in the

saddlery and harness trades rapidly increased during the

19th century:

|

Census

1821

1841

1861

1881

1901 |

|

Number of

people employed

33

171

523

3,492

6,830 |

|

Before the leather trade developed in

the town, Walsall was well known as the centre of the

lorinery trade. Since the 16th century Walsall’s blacksmiths

had been producing hand-forged bits, buckles, saddle trees,

spurs, and stirrups etc. Some loriners diversified into

saddle and harness making, as a way of extending the range of their

products. It seems likely that saddle and harness making in

Walsall developed as a result.

|

|

|

| Read about Walsall's

Leather Industry |

|

| |

|

|

One of Walsall’s oldest

manufacturers, founded in 1760, is Eyland and Sons

Limited, originally based at Rushall Street Works,

number 11 Lower Rushall Street. The firm was established

by Moses Eyland, and produced spectacles and buckles. It

became one of the best known spectacle manufacturers in

the area.

It is listed in the 1818

Staffordshire General and Commercial Directory by W.

Parson and T. Bradshaw as Moses Eyland, optician and

saddler’s iron monger. In the editions of William

White’s History, Gazetteer and Directory of

Staffordshire for 1834, and 1851, the firm is listed in

two sections: buckle makers, and opticians and glass

grinders. In the 1899 Walsall Red Book the firm is

listed as spectacle manufacturers and buckle

manufacturers, but it seems that spectacle manufacturing

soon came to an end.

By the early nineteenth century the factory occupied

much of the row of terraced houses that still stand

today, although some were demolished in the slum

clearances during the 1930s. They were originally small

workshops. Parts of the factory were in a large

courtyard at the back, much of which was destroyed by a

fire in 1878. New buildings were then added behind the

terraced workshops. |

|

The row of houses in Lower

Rushall Street, Walsall. Once the site of Rushall Street

Works. |

|

According to Howard D. Clark in his

book ‘Walsall Past and Present’ published in 1905, the

firm exported large numbers of spectacles to many parts

of the world, but this part of the business was badly

affected by protective tariffs in various countries, and

so the firm diversified into gilding, electro-plating,

nickel plating, and buckle manufacturing.

The business still survives, and

now operates from F. H. Tomkins’ factory in Brockhurst

Crescent, Walsall.

The old workshops in Lower Walsall

Street were renovated in the 1990s and converted into

apartments.

The old courtyard and factory at

the rear is now called Eyland Grove, and is occupied by

apartments and a car park. |

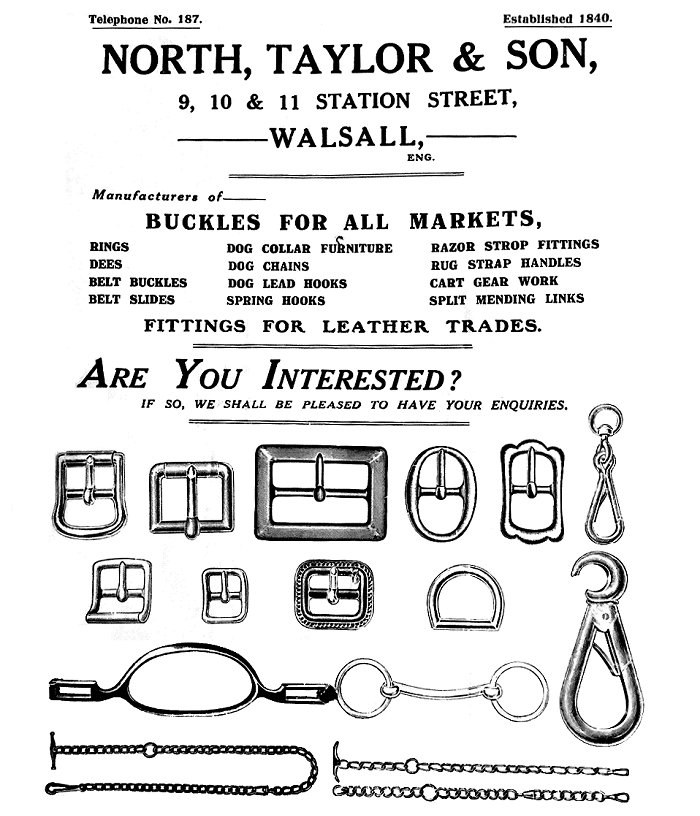

From the 1916 Walsall Chamber of

Commerce Year Book. |

|

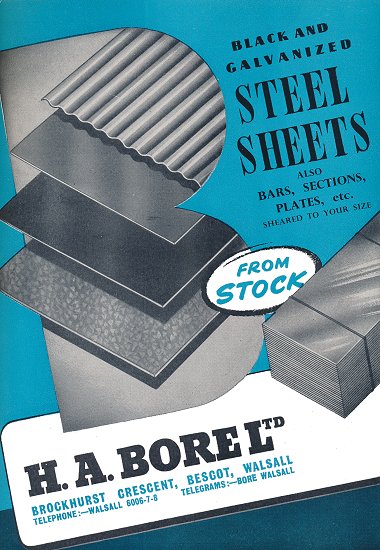

From the 1958 Walsall County

Borough Directory. |

Heavy

IndustriesHeavy industry and

large scale manufacturing came to Walsall in the 19th

century thanks to the building of the Walsall branch of the

BCN, the Wyrley & Essington Canal, improvements to the

roads, and the advent of the railway.

The heaviest industry in the town was

iron-making, which developed due to improved transportation,

and copious supplies of local coal, iron ore, and Wenlock

Limestone, used as a flux in the smelting process. Walsall

like many other Black Country towns had several ironworks

and non ferrous metalworks.

|

An advert from 1935. |

|

An advert from 1935. |

|

Walsall's Ironworks and Metalworks |

|

Foundries |

|

T. Partridge & Company Limited. Structural

engineers |

|

Johnson Brothers & Company Limited. Fencing,

railing, gates |

|

Swallow Motorcycles |

|

Swallow Sports Cars |

|

Kirkpatrick Limited |

Other Industries

Chain making

In the middle of the

19th century, chain making was a significant industry in

Walsall, particularly chains associated with horses and

carts. As the demand for such chains fell in the 20th

century, the industry declined, but in the 1970s Walsall

still had five chain makers, 3 making harness and dog

chains, and two making chains for industrial

applications.

William White's

History, Gazetteer and Directory of Staffordshire

published in 1851 lists the following manufacturers:

|

Dog and Light Chains

Thomas Clark, Wisemore

Samuel Cooper Rycroft

George Griffiths, Stafford Street

Benjamin Harmes, Hammer Forge Lane

Joseph Kendall, Bank Street

Stephen Parker, Stafford Street

Thomas Reynolds, Stafford Street

Joseph Richardson, Wisemore

Joseph Russell, Ryecroft Street

James Shale, Stafford Street and Blue

Lane

Elijah Whitehouse, Stafford Street

Edward Wilkes, Lower Rushall Street

Cart Harness Chains

John

Adams, Birchills Lane

Thomas Boot, Lower Rushall Street

Davis Dewsbury, Wisemore

John Emery, Pool Street

Joseph Moseley, Church Street

Henry Shelley, Green Lane

Samuel Stephens, Ablewell Street

John Watkins, Nichols’ Yard

Edward Webster, Green Lane

Edward Wilkes, Lower Rushall Street

Curb Chains

William Barnett, New Street

John Beebee, Wisemore

William Bellingham, Upper Rushall Street

Joseph Butler, Stafford Street

Joseph Cooper, Stafford Street

Samuel Cooper, Ryecroft

Thomas Cooper, Ryecroft |

|

Curb Chains cont.

Daniel

Derby, Wisemore

George Evans, Thurstan’s Buildings

George Griffiths, Stafford Street

James Hale, Ablewell Street

Isaac Hanby, Lower Hall Lane

Charles Hanby, Hill Street

James Hawcroft, Caldmore

John Hickin, Bank Street

James Holden, Townend Bank

Joseph Lowbridge, Hammer Forge Lane

Joseph Lowbridge, Blue Lane

Thomas Mills & Son, Albert Street

Richard Morroll, St. Pauls Street

George Noke, Green Lane

John Osborne, Blue Lane

Samuel Osborne, Blue Lane

James Parker, Day Street

Stephen Parker, Stafford Street

Charles Reynolds, Stafford Street

Charles Ridding, Stafford Street

Edwin Roper, Hill Street

John Russell, St. Pauls Row

Joseph Russell, Ryecroft Street

Richard Shelley, Marsh Lane

Joseph Somerfield, New Street

Thomas Swan, Caldmore

Charles Webster, Caldmore

John Webster, Green Lane

John Webster, Marsh Lane

William Webster, George Street

Charles Whitehouse, Wolverhampton Street

Thomas Whitehouse, Marsh Lane

James Williams, St. Pauls Row

Simon Williams, Fieldgate |

|

By 1935 the number of

manufacturers had greatly reduced. The following list is

from the Walsall Red Book for that year:

|

Chain Makers

P.

Bull & Son, Margaret Street

W. J. Burns, 12 Carless Street

J. H. Carter, 16 Butts Road

J. A. Dewe, 72 Bath Street

O. D. Guest Limited, 51 Vicarage Street

J. H. Hawkins & Company, 16 Station

Street

J. T. Hyde, 1 Caldmore Road

H. D. Jackson Buckle Company Limited,

Hospital Street

F. Martin, Vicarage Place

S. Middleton, Back 18 Burleigh Street

H. Noakes, 77 Regent Street, Brownhills

T. Russell, 75 Regent Street, Brownhills

Stokes & Sons, Northcote Street

F. H. Tomkins Limited, 14 Caldmore Green

S. Venables & Son, 20 Shaw Street

Walsall Locks & Cart Gear Limited, Neale

Street

Job Wheway & Son Limited, Birchills

Chain Works, Green Lane |

|

|

An advert from 1935.

|

Awl

blades

Awl blade manufacturing began in the

town in the late 18th century, and concentrated in the

Bloxwich area. Awl blades were a necessity in the leather

and saddlery trades until the introduction of stitching

machines which greatly reduced the demand. A few

manufacturers survived in the Bloxwich area, but by the mid

1970s only one still survived, Thomas Somerfield & Sons Limited,

Clarendon Street, Bloxwich.

An advert from 1935.

William White's History, Gazetteer and

Directory of Staffordshire published in 1851 lists the

following manufacturers:

|

Walsall James

Ashwell, Caldmore

Emma Collins, Pleck

Clement Ross, Bradford Street

James Ross, Little London

Bloxwich

Charles Beech

Samuel Edge

George Evans

Henry Hackett

Charles Jones

Mark Nicholls

John Nicholls

Michael Parker

Michael Partridge

Thomas Partridge

John Reeves

Thomas Reeves

Isaiah Ross |

|

Bloxwich

cont. Thomas Ross

& Sons

Edward Russell

Thomas Somerfield

John Stokes

James Taylor

James Taylor junior

Daniel Wilkes

Thomas Woodall

Short

Heath

John Bullock

James Hodson

Mrs. Lebond

Henry Mason

Thomas Parker

Samuel Somerfield

William Somerfield

David Wilkes

Thomas Wood |

|

The manufacturers in 1935.

From the Walsall Red Book:

|

W. J. Goodwin & Son,

Burrowes Works, Wolverhampton Road

W. C. Harvey, 30 Bell Lane

E. Hill, 20 The Green, Bloxwich

John Nicholls & Beddows, Wallington Heath,

Bloxwich

J. Parker, 26 Marlborough Street

A. Ross & Company, 76 Sandwell Street

F. J. Ross & Sons, 140 Sandwell Street

Ross & Son, 501 Bloxwich Road

Somerfield & Sons, Clarendon Street

H. Vale & Sons, 18 Holtshill Lane |

|

|

|

Lock

Making

In the 19th century, Walsall had a

number of lock manufacturers, mainly specialising in cabinet

locks, and padlocks. In the 20th century the number fell.

Only four remained in the 1970s, and about the same

number remain today.

William White's History, Gazetteer and

Directory of Staffordshire published in 1851 lists the

following manufacturers:

|

Cabinet

Locks

James Archer, Prospect

Row

Charles Carless, Hill Street

William Duncomb, Blue Lane

John Lowe, George Street

William Marshall, Hammer Forge Lane

John Purchase, Blue Lane

Edward Rose, Caldmore

Mrs. Round, Birchills

Charles Tuckley, Birchills Lane

Windle and Blythe, King Street

Padlocks

Elias Ash, Stafford

Street

John Bates, Intown Row

John Bates, Whitehall |

|

Padlocks

cont.

James Hart,

Wolverhampton Road

Henry Johns, Garden Walk

Joseph Mills, Mountrath Street

Mills and Tibbits, Upper Hall Lane

Rim

Locks

Mrs. Webster, Adams Row

Trunk

Locks

Samuel Bayley, Station

Street

Stock

Locks

Stephen Yates, Brewer’s

Yard |

|

Manufacturers in 1935. From the Walsall

Red Book:

|

Ash & Rogers, Pargeter

Street

Bloxwich Lock & Stamping Company, Bell Lane,

Bloxwich

J. H. Goodman, 37 Harrison Street, Bloxwich

Hadley & Company, Mountrath Street

W. J. Heap & Son, 84 Lower Rushall Street

H. Johnson & Company, 150 Portland Street

D. Lycett, 45a Portland Street

Neville Bros & Company, Wednesbury Road

F. T. Sanders, 77 Field Road, Bloxwich

E. F. Sharpe, 14 Freer Street

A. E. Stych, 74 Pargeter Street

Walsall Locks & Cart Gear Limited, Neale

Street

A. Wilkes, Bloxwich Works, Bloxwich

O. Wilkes, 39 Cairns Street

Stephen Wilkes & Company, Pargeter Street

S. Wilkes & Sons Limited, Park Road,

Bloxwich |

|

|

|

Brush

Making

Brush making became an important

industry in Walsall in the late 19th century. It began in

the 1760s with just a handful of makers including Joseph

Nightingale, who had a workshop in Chapel Street; Hannah

Reynolds; George Reynolds, based in Church Street; and Simon Burrowes whose premises were in Rushall Street. James

Pigot’s Commercial Directory for 1818 lists the following

makers:

|

Thomas Brown, (bone and

ivory) Rushall Street

Joseph Buss & Company, ( bone) Dudley Street

John Groves, (wood) Stafford Street

Charles Hall, (wood and bone) Park Street

Thomas Mele, (bone) Rushall Street

Joseph Reynolds, (bone and ivory) Rushall

Street

Thomas Thornhill, Stafford Street |

|

The industry slowly grew. William White's History, Gazetteer and

Directory of Staffordshire published in 1851 lists the

following manufacturers:

|

John Adkins, Peal

Street

William Allen, Ablewell Street

David Clarke, Park Street

Joseph Cook, Bradford Street

James Eagles & Sons, Park Street

Maria Fletcher, Lower Rushall Street

Philip Holloway, Wisemore

Richard Thornhill & Sons, Bridge Street

William White, Stafford Street

Bone &

Ivory Brushes

Joseph Busst, Lower

Rushall Street

Joseph Busst junior, Stafford Street

George Jones, Park Street |

|

By the mid 1860s around 100 people

worked in the industry, making brushes of all kinds, ranging

from paint brushes, clothes brushes, and shoe brushes, to hair

brushes. In the latter part of the century the industry was

mechanised, and production vastly increased. Most of the

factories were near the town centre, but three were in

Bloxwich.

The number of manufacturers slowly

fell, and by 1921 only nine were left. The number continued

to fall to leave only three in the 1960s: Bradnack & Son at

Defiance Works in Birmingham Road, Busst & Marlow in Lower

Rushall Street, and Vale Brothers in Green Lane. In 1967 J.

Brierley & Sons Limited moved to Forest Works in Forest Lane

from Birmingham, to produce industrial brushes and personal

giftware.

Busst & Marlow closed in the early

1970s, and Vale Brothers acquired Bradnack & Son, and moved

to Defiance Works to concentrate on production of grooming

brushes for animals. The company is now based in Long Street

and also makes horse-whips,

There was also the United Society of

Brushmakers, which met at The Prince in Delves Road. |

|

Manufacturers of Clothes

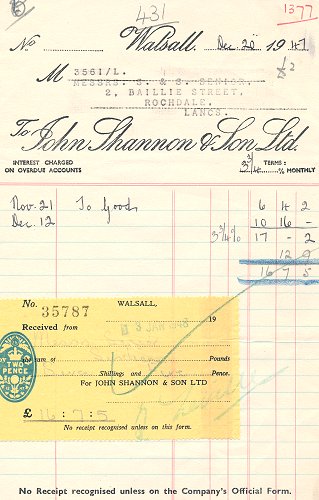

By the late 19th century Walsall was at

the centre of a large clothes manufacturing industry. The

best known manufacturer was Shannons, founded by Scottish

draper John Shannon, in 1826. In 1845 he opened a shop in

George Street, on land he leased from Lord Bradford, and in

1870 opened a workshop there. The business employed 20

people to make men’s clothing for the local market. He was

mayor of Walsall in 1850-51. After his death in 1875 he was

succeeded by his son Edmund John, who greatly expanded the

firm, mainly due to the recently invented sewing machine.

|

|

A Model Tailoring Factory.

From the Birmingham Daily Gazette, 11th May,

1888

Messrs. Shannon and

Sons, of Walsall, employ altogether 937

hands, 800 on the premises, 137 finishers

off the premises. They turn out in very busy

times 10,000 garments a week, and pay about

£800 in wages. The conditions that prevailed

during a visit paid yesterday, without a

minute's warning, may presumably be accepted

as normal conditions.

Every room was fairly

ventilated. Half the windows were open, half

the shafts and revolving fans and airbricks

and soon were blocked up as the result of

the workpeople's own carelessness. In one

room a girl thoughtlessly placed her shawl

and bonnet on the spout of an airshaft; in

another, a lad, finding the ventilating

chamber a handy receptacle for waist

material, stupidly filled it up. But no

system can stop such blunders as these.

In the largest room,

where 200 women and girls were employed,

complaint was made that there was too much

air. There were no draughts, but the

powerful ventilators in the V-shaped roof

sucked up all the foul air and made the room

cool. Gas-heated pressing irons are in use,

and to minimise the heat, experiments are

being made with escape flues, which are

intended to carry off the air fouled by the

gas burnt. The electric light has been

recently installed, and now every workshop

is fitted with arc lamps.

The pressing room is

the only room uncomfortably warm, night or

day, and it is proposed shortly to transfer

the ironers to a larger, loftier, and better

arranged gallery, with specially contrived

flues and fans to carry off the hot air.

Captain Bevan, the Walsall Inspector of

Factories, has no improvements to suggest,

the employees have no blame even for one's

private ear.

The books show that

fair wages are being earned. Last week the

men, women, and children were exceptionally

busy, and they will remain busy for two or

three weeks so the wages paid last Saturday

would be somewhat misleading. A glance at

the average for a year is more interesting

and instructive. There are 300 machines at

work, managed by girls ranging from 14 to 25

years of age. These earned last year -

according to age and ability - 9s.4d.,

12s.6d., 16s.3d., 7s.10½d., 8s.9d., 10s.8d.,

17s.1d., 5s.3d., 16s.ld. These are figures

taken haphazard from hundreds of ledger

entries.

Girls are generally

engaged at 13 or 14 years, and earn little

for two years; then, according to whether

they are clever or stupid, they carry home

from 7s. - 12s. a week; if they remain

unmarried at 21, they can earn 18s. or 20s.

in busy times and 15s. a week all the year

round.

Juvenile's clothing is

sold now at exceedingly cheap rates. A boy

of eight years can be rigged out in quite a

dainty costume for 3s. 3d. - jacket, blouse

and knickerbockers. Yet in the making of

these inexpensive suits, girls average

8s.ld., 7s.l0d., 9s.4d., and 13s.8d. a week,

and averaged a little less for the year.

Coat machinists who must possess more skill,

earned last week - 12s.9d., £1.3s.9d.,

8s.10d., and £3 a week, and averaged a

little less for the year. Vest machinists do

not earn quite so much; trousers baisters

can gain from 12s.11d., to 23s.6d., per

week; coat and vest buttonhole makers from

6s.10d., to 18s.8d.; coat pressers were paid

from £1.7s. to £1.16s; trouser pressers were

paid as much as £2.10s. (an average week

would represent about 30s.) These wages are

earned by working ordinary hours - eight to

eight. The clean, neat clothes and bright

faces of the people indicate that the only

sweating they experience is that required by

any diligence in any manual trade. |

|

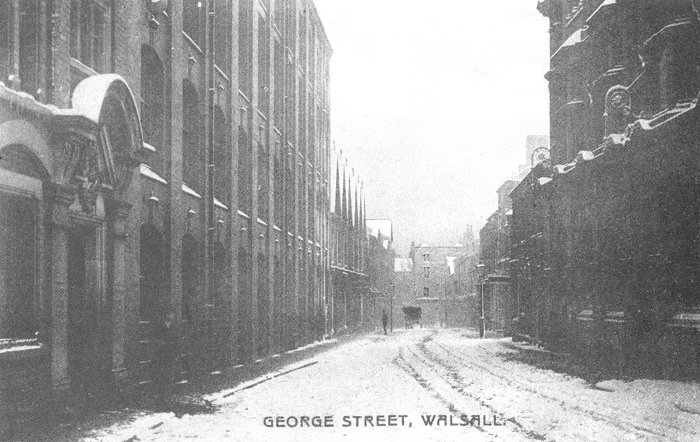

A wintry view of George Street, with

Shannon's Mill on the left. From an old postcard.

|

By 1887 the workshop had become too

small and so the impressive four storey Shannon’s Mill was

built. The brick building was in three parts, two of eight

and eleven bays, and a central part with eight bays and

elaborate stone stringing.

Around 1890 the firm became John

Shannon & Son Limited, and at the turn of the century the

building was greatly extended. By 1905 Shannons employed

over 2,000 people, mainly 14 to 25 year old girls who

operated the 300 or so machines. The girls started work at

the age of 13 or 14 and were not paid at all for the first

two years. Before they were paid they had to learn all

aspects of the trade and assisted other workers. After two

years they could earn between 7 shillings and 12 shillings a

week.

Shannon’s products included wholesale

clothing manufacture, and high quality ready to wear men’s

and boy’s suits, and ladies’ costumes. In 1913 Edmund

Shannon was succeeded by his son John C. Shannon.

After the First World War there was a

depression in the trade, which in 1926 resulted in the

resignation of John Shannon, and the company going into

liquidation. The company managed to survive, and went public

to become John Shannon & Sons Limited with the Shannon

family as major shareholders.

|

| |

|

Read a description of a

visit to Shannons in 1897 |

|

| |

|

|

Shannon's Mill from 1977.

Courtesy of Paul

Bowman. |

|

During World War 2 Shannons produced

large numbers of military uniforms and the future looked

bright. After the war rates of pay slowly increased, and as

Shannons were unable to pay higher wages, the number of

employees fell, and the company reduced in size.

In 1973 Shannons still occupied the massive old works, and so the

decision was taken to let parts of the building to other

companies, including part of the Walsall leather goods firm

W. A. Goold (Holdings), the saddlery firm E. Jeffries &

Sons, the jewellery division of Pearmak, and Leonard Neasham,

the gentleman's outfitters.

Shannons ceased trading in 2000 and the building remained

empty for several years. It was due to be the centrepiece of

a £53m regeneration project for St Matthew's Quarter, but on

Friday 3rd of August, 2007 the mill suffered badly from a

mindless arson attack.

The building was badly damaged, 60

percent of it collapsed. It had been the largest fire in the

town for 25 years. By the end of the month the dangerously

unsafe building had been demolished. A sad end to such a

wonderful local landmark.

|

An advert from 1953. |

|

Another clothing manufacturer, Stammers

was founded in 1904. The firm was initially based in Dudley

Street, but in 1906 moved to New Street after becoming a

subsidiary of the Foster Bros. Clothing Company Limited of

Birmingham. The factory was extended around 1925 and

specialised in men's and boys' clothing.

The 1935 Walsall Red Book lists the

following manufacturers:

|

Mark Cohen & Company, 2

Whittimere Street

T. Bednall & Company, Mountrath Street

Bradbury & Company, Teddesley Street

Harris Davis (Walsall) Limited, Adams Row

Hayward & Jones, 41 Station Street

Marshall & Hamblet, Littleton Street

Norton & Proffitt, Midland Road

Parkinson (Walsall) Limited, Chuckery Road

J. Shannon & Son Limited, George Street

Stammers Limited, New Street |

|

There were ten clothing manufacturers

in1963, but only six by 1973. |

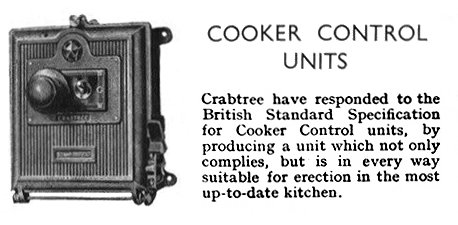

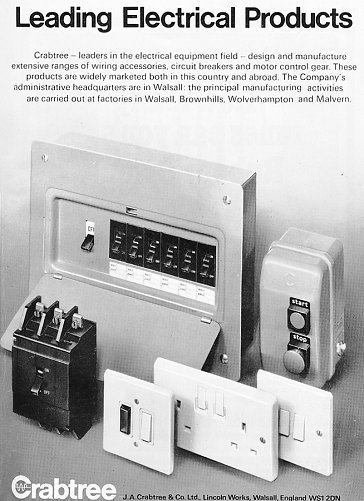

| Electrical Engineering

One of Walsall’s most famous manufacturers was J. A.

Crabtree & Company Limited based at Lincoln Works in Beacon

Street.

The business was founded by John

Ashworth Crabtree who was born in Broughton, Lancashire,

just north of Preston on October 24th, 1886. His father died

when he was just five years old, and his mother and her

family moved to Yardley in Birmingham. John’s career began

as an engineering apprentice.

|

| He initially worked for Verity's Limited, electrical

manufacturers based at Aston in Birmingham, and then moved

to J. H. Tucker Limited, manufacturers of switchgear in Tyseley, Birmingham. After working in Tucker’s workshops, he

moved to the drawing office, and whilst there invented, and

patented an improved type of switch. John decided to start

his own business, to manufacture the patented quick make

and brake switch, after Tuckers refused to do so.

In 1919 he

founded J. A. Crabtree & Company in a small disused leather

works in Upper Rushall Street, Walsall. The switch became a

great success, orders poured-in, and the company soon

outgrew the small factory.

In 1923 the firm acquired seven acres

of land in the Chuckery, alongside Beacon Street and Lincoln

Road, where a new factory called Lincoln Works was built. |

John Ashworth Crabtree. |

|

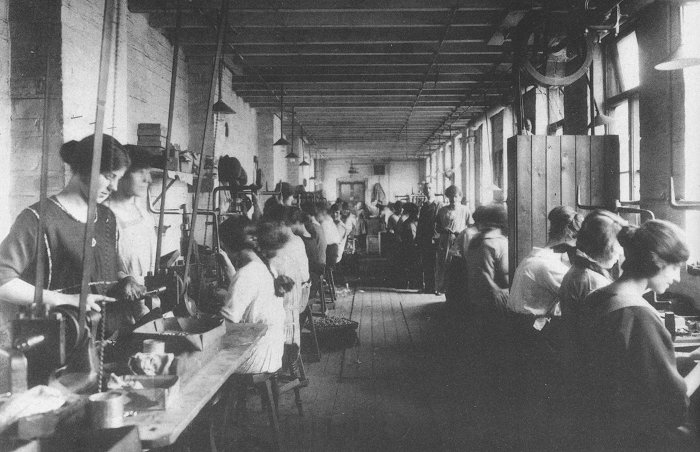

One of the workshops in Upper

Rushall Street. |

|

Lincoln Works. From the 1974 Walsall

Handbook. |

It

was named after President Lincoln who John greatly admired.

By 1926 around 600 people were employed on the site. The

business prospered, and in 1929 John Crabtree developed the

first plastic moulded switch which he called ‘The Lincoln

Switch’.

The plastic that he developed was called ‘Jacelite’

to distinguish it from bakelite. |

|

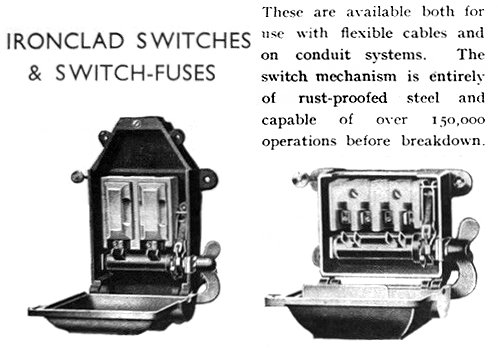

An advert from 1935. |

| An advert from 1935. |

|

|

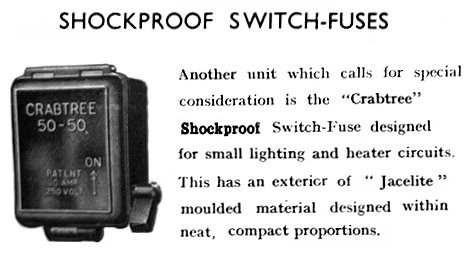

An advert from 1935. |

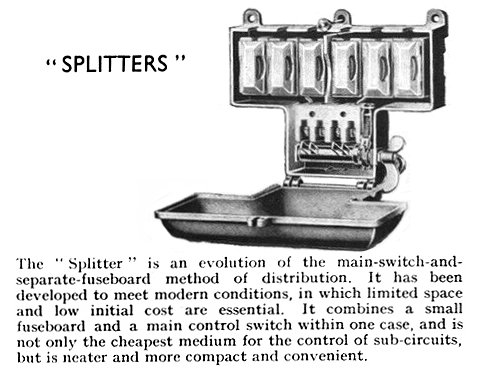

| An advert from

1935. |

|

|

By the early 1930s Lincoln Works had

grown into the best equipped factory of its kind in the

country, and employed around 1,000 people.

In the autumn of

1935 John went to America on a business trip, and caught

pneumonia, from which he died on November 27th, at the age

of 49.

After John’s death, his widow took a

leading role in the company, and in 1944 her son Jack joined

the Board after graduating from Queen’s College, Oxford. He

became Chairman and Managing Director in 1958.

| |

|

|

|

View pages from

the staff magazine |

|

View some of the

company's products |

|

|

|

|

An advert from 1974. |

| |

|

| Read about Crabtree in the

late 1940s |

|

| |

|

|

An advert from November 1954. |

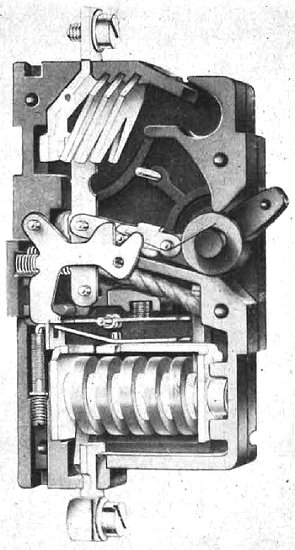

Two new Crabtree products featured in an article in 'The

Engineer', 15th April, 1960.

| The new C-50 miniature

circuit-breakers are designed to

challenge the use of rewirable fuses

for sub-circuit protection. As such

they can be fitted in what is

claimed to be the first all

insulated consumer unit to give

circuit-breaker protection to the

sub-circuits. The C-50 circuit

breaker has an electromagnetically

operated tripping mechanism, all

ratings being set to trip on a

sustained overload of 30 percent.

"Nuisance" tripping by harmless

transient overloads is prevented by

a built-in inverse time-current

delay device.

It will be seen from the

photograph that the operating handle

controls the moving contact through

a collapsible over-centre toggle

mechanism. Since the handle is in

positive control in the "On" and

"Off" positions, the breaker can

always be opened or closed manually.

The moving contact traverses the

'V' shaped slots in a series of arc

grid plates at the top of the switch

and is shown in the closed position.

The overload coil and time delay

device are located in the bottom of

the moulded case of the circuit

breaker. |

Miniature circuit breaker (C-50)

set to trip on 30 percent overload,

and fitted with inverse time delay. |

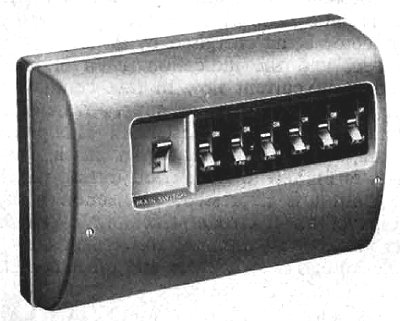

The All-insulated consumer unit

enclosing a 60A double-pole

isolating switch and six miniature

circuit breakers, of ratings from

2.5A to 50A. |

The fully-insulated consumer

unit consists of a moulded cover in

a silver-grey colour, enclosing a

60A double-pole isolating switch and

up to six miniature

circuit-breakers, which can be of

various ratings, from 2.5A to 50A. |

|

|

|

|

In 1961 the company launched the UK’s

first circuit breaker, and continued to produce vast numbers

of plugs, sockets, switches, and motor control gear. By the

late 1960s the workforce had grown to over 3,000.

|

| |

|

| View some images, and the

programme from the Queen's visit to Lincoln Works in May

1962 |

|

| |

|

| In 1972

the company was acquired by Ever Ready, and after a

succession of owners, Lincoln Works closed in 1997 and

production was moved elsewhere. Crabtree became the largest

private employer in Walsall, so the closure came as a great

blow to the town. |

|

An advert from 1935.

The earliest electrical engineering

company in the town was possibly the Walsall Electrical

Company founded in 1884 by Frederick Brown to

make bells, electrical fittings, fuses, indicators, lamps,

and switches. It had an office at 57 Bridge Street, a

factory at the rear of 57, 59, 61 and 63 Bridge Street, and

became a limited company on the 2nd December 1892. There

were three directors; Frederick Brown the Managing Director

and major share holder, John Hildick the Chairman, and Henry Nicklin. There was also an office in Birmingham.

The Managing Director's salary was £350

per year, plus 25 percent of the profits. The authorised

capital of the company was £10,000 in £10 shares. Brown

applied for, but did not always register the patents for the

numerous electrical instruments and appliances that he

developed, including advertising signs, galvanometers,

lamps, medical induction coils, switches, and voltmeters.

Frederick Brown was born in Pensnett in

March 1848. He was a member of an old Quaker family, and

educated at the Friends School, Ackworth in Yorkshire. He

began his career as a photographer with a Mr. Draycott at

their premises at The Bridge. In 1881 he became manager of

the National Telephone Company, and left in 1884 to set up

the Walsall Electric Company.

|

|

An advert from 1954. |

In 1891 he became an electrical

engineering consultant to Walsall Council to advise on the

method of power transmission to be used by the South

Staffordshire Tramways. After a fact-finding trip to

America, he submitted his report in July 1891, and was later

appointed to supervise the installation of the overhead

cabling for the trams.

In February 1893 Brown was appointed by

the council to advise on their electric lighting scheme. He

became a leading member of Walsall Chamber of Commerce, and

was President in 1910 and 1911.

By 1901 the firm had appointed agents

in London and Liverpool, and after making an initial loss

became profitable. John Hildick resigned from the Board in

November 1908, and was replaced as Chairman by Henry Nicklin.

At the same time a new director, James Osmonde Dale was

appointed.

Frederick Brown died on 8th August, 1913

at Streetly. He was replaced by F. Bailey.

|

| The early 1930s was a bad time for

the company which was not profitable. It became Walsall

Instrument Limited, on 10th August, 1932, and produced

switchboard instrumentation, charging apparatus and

regulators at Faraday Works, Algernon Street, Walsall.

Sadly things did not improve and the business went into

creditor's voluntary liquidation on 26th April, 1933. The company managed to survive, and

changed its name back to the Walsall Electrical Company

Limited. The product range was extended to include crane

plug boxes. The business again became profitable, employing

around 50 people.

| View some of the

company's products from the 1947 and 1961 catalogues |

|

In 1949 the company registered the 'WALTRIC'

trade mark, but unfortunately the firm failed to invest in

research and development, and so the products became

outdated as technology changed. The products in the 1947

catalogue appear to be from the early 1930s rather than the

late 1940s. In 1983 the firm took out a

medium term loan to finance the development of a range of

panel meters, which were quite successful. In 1992 the

business merged with Beacon Instruments Limited to provide a

wider product range, but suffered from increased competition

from cheaper products made in the Far East and India. In

2002 the business was put up for sale, but little interest

was shown, and it closed in 2004.

There were several other electrical

manufacturing companies in Walsall including Bayley Bros.,

the Central Manufacturing Company, The Mechanical &

Electrical Engineering Company (Walsall) Limited, and Electronics Design

Associates.

|

| |

|

| Read about the Mechanical &

Electrical Engineering Company (Walsall) Limited |

|

| |

|

|

An advert from 1976.

Other

Locally Made Products

|

|

An advert from 1902. |

Packing cases and cardboard boxes have

been made in Walsall since the 19th century. In 1834 packing

cases were being made by James Rooker Mason in High Street,

and Mary Silleter in the Square.

In 1935 they were produced

by T. Ginder & Son Limited of Whittimere Street, and

Bradford Street; and John York of 19 Goodall Street.

In 1935 cardboard boxes were produced

by Mrs. F. Burton, 33 Hart Street; B. Fenton, Midland Road;

G. Parsons & Company, Back 33 Station Street; A. Platt, 115

Bridgeman Street; and The Walsall Box Company in Bank

Street.

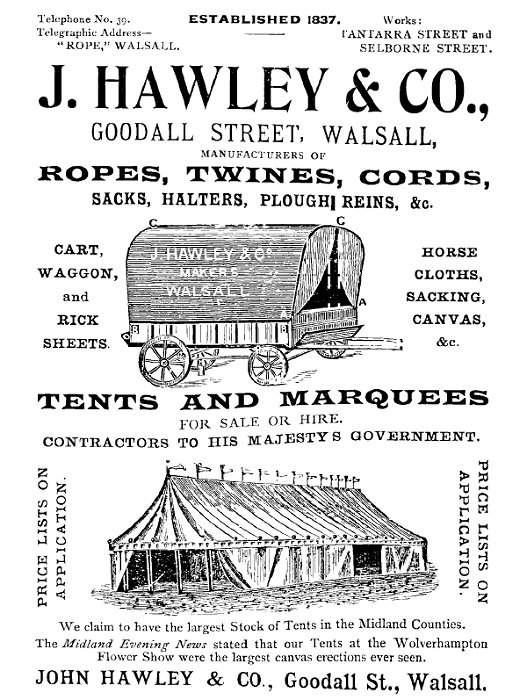

Other products included India rubber

goods, rubber stamps, rope and twine, riddles and sieves,

and plastic mouldings, which were produced by E. Perkins &

Company Limited in Selborne Street, and the Plastics

Products Company in Midland Road. |

| In the late 19th century and early 20th century,

many bicycles were made on a small scale in most of the

local towns, often at the back of a shop. The industry

relied on locally made cycle accessories, many from

Birmingham, and locally made tube for the frame. There

were at least five manufacturers in Walsall: J. E. Wheway, builder of 'Cyverite'

cycles; the Vanguard Cycle Company Limited, manufacturer

of 'Vanguard' cycles, Ford & Butler, 15 Bradford Street;

John More & Company, Highgate Cycle Works, Sandwell

Street, manufacturer of 'Highgate' cycles; and Harry

Lester of 25 Bradford Street. |

An advert from 1902.

An advert from 1899.

An advert from 1899.

An advert from 1892.

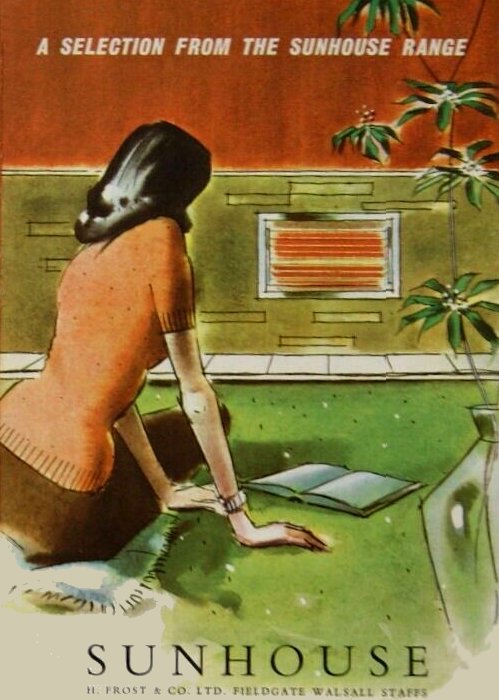

| An advert from 1958. |

|

|

An advert from 1958. |

An advert from 1958.

An advert from the 1960s.

An advert from the 1960s.

An advert from the 1960s.

|

|

|

|

|

Return to Into

The 19th Century |

|

Return to

the beginning |

|

Proceed

to Late 19th Century |

|