|

There would have been a tiny

settlement in the area by the 8th century when the

town’s name was first recorded. Willenhall lay in part

of Cannock Forest, an area much favoured by the Mercian

Kings for hunting the wild boar,

wolves, and possibly deer, that resided here. It seems likely that King Aethelbald, who came to power in 716, used the hamlet as

a centre for his hunting activities. In the 22nd year of

his reign he signed a charter at the hamlet, to reduce

certain taxes payable by the Abbey of Minstry in the

Isle of Thanet. He did this for the good of his soul,

and to help ensure a place in the afterlife.

The contents of the charter were

recorded in original Latin by John Mitchell Kemble in

his 6 volume “Codex Diplomaticus Aevi Saxonici”, printed

in 1839 to 1848. Kemble made an extensive study of

Anglo-Saxon, and Norman legal and administrative

documents, from the British Museum, his own collection,

and various libraries. The contents of the charter were

also published in the original Latin form in Thorpe’s

“Diplomatarium Anglicum” in 1865, and Birch’s

“Chartularium Saxonicum” in 1885.

The charter is worded as follows:

| From sinful Aethelbald, King of the

Mercians, who yields to Mildrith, Abbess of Minster, the

tax on a ship of burden, and grants that throughout the

kingdom it remains free of royal tribute. I, Aethelbald,

King of the Mercians, perform, as far as in my power

lies, acts of gratitude to Almighty God, who has deemed

me worthy to be chosen for so high a grade of

distinction, out of the humble and unquiet life which I

led for the space of so many years.

Therefore, for the

salvation of my soul, and in return for the liberal

offerings of the prayers of holy servants and handmaids

of God, I freely bestow upon the churches of God, those

things which are brought under my power, and the

bounteous gifts of our Almighty Lord and Saviour Jesus

Christ. And to thee Abbess Mildrith, and to thy church,

I give up and remit tax due upon a ship of burden, which

is gathered by way of tribute by our toll collectors, so

that throughout the kingdom the ship may remain free

from all royal impost and tax.

If any attempt to infringe upon

this gift we have granted, either in great part or in

small, let him know that he remains expelled from our

communion, and wholly cut off from the company of the

pious.

Signed by Aethelbald, Cuthraed,

Sileraed, Worr, Cotta, Cynric, Wilfred, Lulla, and Oba.

This was excecuted on the fourth

day of the Kalends of November, in the 22nd year of our

reign in the place which is called Willanhalch.

|

A second copy of the charter also

survives, which states that this is the 15th decree made

in the place which is called Willanhalch.

The well-known, acknowledged, 19th

century authority on Saxon place names was William Henry

Duignan, a Walsall Solicitor, who wrote books about place names in Staffordshire, Warwickshire and

Worcestershire. He stated that the name Willanhalch

cannot be applied to any other place in Mercia, or Saxon

England, than Willenhall in Staffordshire. There is

another Willenhall on the outskirts of Coventry, but

that was known as Wylnhale, and any charter signed there

would include the Coventry name.

Willanhalch in Anglo Saxon means

the meadowland of Willan, presumably the local land

owner, head of the ruling family, or local chieftain.

The old English word for meadowland, ‘halch’, was

shortened and modified in the course of time to ‘hall’.

Other similarly modified local place names include:

|

Tettenhall |

Possibly Tetta’s hall |

| Pelsall |

Peol’s hall |

| Codsall |

Code’s hall |

| Ettingshall |

Hall of the Etti

family |

By the 12th century the name had

changed to Willenhale, and Willenhal.

In the year 913 Stafford became a

secure, fortified stronghold, under Queen Aethelfaed,

and soon replaced Tamworth as the capital of Mercia.

Within a few years the new Shire of Stafford was formed.

At this time the country was divided into ‘Hundreds’,

each consisting of an area which roughly supported 100

households. The Shire of Stafford was divided into 5

'hundreds'; Cuttlestone, Offlow, Pirehill, Seisdon and

Totmonslow. Willenhall was part of The Hundred of Offlow.

Each hundred was headed by a hundred-man or hundred

elder, who oversaw justice and administration in the

area, organised the supply of soldiers, and led them

into battle. Hundreds were usually named after the place

where meetings were held to discuss local issues, and

where trials took place.

At this time Willenhall would have

been a small hamlet, consisting of a few single-storey

timber-framed buildings, possibly clad with timber, or

even wattle and daub, and covered with a thatched, or

turfed roof. Timber would have been in plentiful supply

and so was an obvious building material. There would

have been a hearth for a fire, but no chimney, the smoke

escaped through the roof. All the furniture such as

beds, benches and tables would have been made of wood.

Valuable items and tools would have been stored in a

wooden chest.

Some Saxon houses were built above

a hole, up to 9 feet deep, which may have been a

basement below a wooden floor. Around the houses would be farm

land for crops, and grazing for cattle.

Under new ownership

By 1086 Willenhall had come under

the control of Wolverhampton, but some of the events

that led to this are unclear.

According to tradition, King

Wulfhere founded the Abbey of St. Mary at Wolverhampton

(on the site of St. Peter’s Church) in 659, but there is

no proof of this. However in 985 King Aethelred gave

several pieces of land to Lady Wulfrun in a royal

charter, including Bilston, Sedgley, Wednesfield, Upper

Penn, and Trescott. In his charter Aethelred describes

the area of land in terms of its boundaries.

In 994 the Lady Wulfrun gave the

pieces of land to the Abbey of St. Mary ‘for the good of

her soul’. The gift included Bilston, but made no

mention of Willenhall. The Domesday Book of 1086 does

include a reference to Willenhall, stating that part of

it belongs to the church; the Deanery Manor of

Wolverhampton, (St. Mary’s), and the remainder belongs

to the King, becoming part Stow Heath Manor in

Wolverhampton. At this time Bilston no longer belonged

to St. Mary’s, it was partly owned by Stow Heath Manor,

and partly by the Deanery Manor of Wolverhampton. It is

possible that an exchange of land was made between the

King and St. Mary’s, so that part of Willenhall came

under the ownership of St. Mary’s, and part of Bilston

belonged to Stow Heath Manor.

Norman Britain

After the Norman invasion in 1066,

William the Conqueror made it known that he personally

owned all of the land in the country. He appointed

around 200 barons as tenants in chief, and allowed them

to hold large areas of land, in exchange for the payment

of taxes, and the provision of soldiers when necessary.

The system, known later as feudalism was the key to the

Norman’s success.

The Normans held on to the Saxon

‘Hundreds’, but carved-up the land into areas called

manors, each controlled by a baron, or Norman Lord. They

had to take an oath of loyalty to the King, carry-out

any required duties, and pay taxes for their land. Each

manor would include several villages whose inhabitants

were called peasants. There were several classes of

peasant. The highest was a freeman who was free to

pursue a trade. The other classes were owned as part of

the land, and were not free to move around.

In 1085 the Danes threatened to

invade, and so William decided to commission a detailed

audit of the country, to extract all of the taxes owed

to him, and to ensure that he got the maximum number of

soldiers to deal with the expected invasion force. The

survey was so detailed that an entry in the Anglo Saxon

Chronicle states that ‘not even an ox, or a cow, or a

swine was not set down in his writ.’ It seemed so

invasive, and all-seeing, that it felt as though

judgement day had come. As a result it became known as

the Doomsday Book.

All 400 pages of the book, record

in extraordinary detail, how the Normans organised their

new kingdom. The entry for Willenhall is as follows:

|

Land of the King

The King holds Winehala. There are

3 hides. The land is 4 carucates. There are 5 villeins

and 3 cottagers, with 3 ploughs. There is one acre of

meadow. The value is 20 shillings.

|

|

Land of the Clergy of Handone

The Canons themselves hold 2 hides

in Winehala. The land is one carucate. There are 3

villeins and 5 cottagers having 3 ploughs.

|

The King had 3 hides, each would be

approximately 120 acres, and 4 carucates, each being an

area of land equal to the amount that could be worked by

a team of 8 oxen. He also owned 1 acre of meadowland.

The 5 villeins were nominally free inhabitants of the

village, who worked the King’s land in return for a

small piece of land to work themselves. They also paid

rent. The 5 cottagers were peasants, lower on the social

ladder than a villain, with fewer privileges. The 3

ploughs meant that there was enough land on the estate

for 3 teams of 8 oxen to cultivate. It was also used to

assess the value of the estate for taxation.

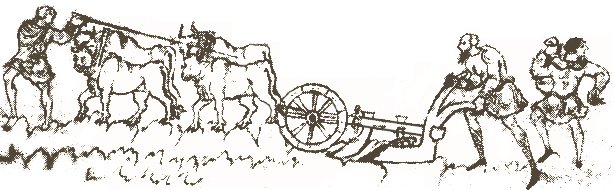

Oxen pulling a plough.

The church’s land was much smaller

(one quarter of the size), with no meadowland, 3

villeins and 5 peasants. Its taxable value would have

been far less.

Everything on the estate would have

been owned and controlled by the manor, or the clergy,

including property, money, religion, and even marriage.

There were labour services to do on the land, and heavy

rents to be paid. The majority of food produced, and

animals reared, were consumed by the lord of the manor

and his household. Many families lived off a simple

vegetable soup called pottage. The average life

expectancy at the time was just 25.

|