|

|

Of the folklore associated with the 5

Victorian hospitals developed in Wolverhampton, namely The

General (opened in 1849, later The Royal), the Eye Infirmary

(opened in 1881), the Isolation Hospital (opened in 1884), the

Surgical Dispensary for Women (opened in 1886), the Queen

Victoria Nursing Institute (opened in 1895) and the Women’s and

Children’s Convalescent Home (opened in 1873); none have created

more parental concern than for a child to be taken to the

Isolation Hospital that treated ‘fevers’.

The incidence of these diseases had been of

enormous proportions throughout the Victorian period, initially

both cholera and smallpox had caused high death rates in both

Wolverhampton and Bilston. With the resultant improvements in

both water supply and sewage disposal, cholera had considerably

dissipated by the early 1880s but increases with the zymotic

diseases was markedly evident.

|

|

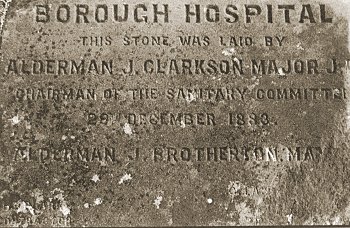

The foundation stone. Courtesy of Neil Fox.

|

Dr. Henry Malet, the then Medical Officer of Health and Honorary

Consultant Physician at the General Hospital, pressed the local

authority to provide a facility for the isolation and treatment of

patients with such conditions. Duty was done and the first such

hospital facility built and supported by Wolverhampton Borough

Council was enacted in 1883 with the laying of the foundation stone.

The hospital opened its doors on the Holly Hall estate in Pond Lane

on the then edge of town on the 6th February 1884.

|

| The immediate admission of some 35 patients with

smallpox, of whom 4 died was conclusive evidence of the hospital’s

necessity. Additionally it was recorded that in the third quarter of

1884, 106 deaths from Infantile Diarrhoea occurred with the

resultant concerns. With some improved pick up in vaccination by

1885, smallpox had receded only to be overtaken by the next cyclical

disease of Scarlatina (Scarlet Fever). |

| During this year some 264 patients were admitted of

whom 40 died, some 15% compared with a death rate in the previous

decade of 57%. By 1892 the hospital facilities had been considerably

enhanced with two pavilions, which with the wooden annexe of two

wards, plus administrative buildings, nurses accommodation and

laundry, plus disinfecting facilities offered good local care. |

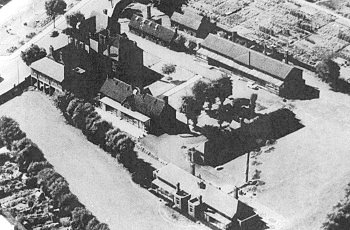

An aerial view of the hospital. Courtesy of

Neil Fox. |

|

In 1894 a recurrence of Smallpox flared with 67

new cases, in addition Diphtheria, Measles and Typhoid continued to

present pressing problems. It is interesting to read in the History

of St. Stephen’s School, Springfields that complete closure of the

school was necessary due to the numbers of children with measles.

The number of related deaths from Tuberculosis in Wolverhampton

peaked at this period to 150, but fell back at the turn of the

century to the low 100s.

Throughout this period electric light was

installed and a further isolation hospital was opened at Moxley in

1923. The Schick test was introduced resulting in immunisation for

all children in 1928 but the beneficial uptake and reduction in the

disease was not evident until the 1940s.

|

|

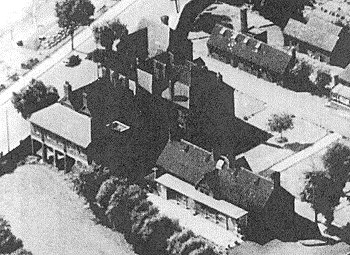

Another view of the hospital. Courtesy of Neil

Fox.

|

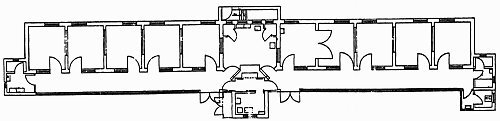

In 1928 a further cubicled ward of ten beds was opened and after

patient numbers increased the hospital a training school for the

Infected Diseases Nursing Certificate by the GNC. Whilst the war

years saw a marked reduction in the incidence of most infectious

diseases, both poliomyelitis and tuberculosis continued to cause

concern, the later condition requiring many weeks of treatment and

bed rest. The available 66 beds at Parkfields were insufficient and

many local patients were sent to Prestwood, Kinver and elsewhere.

|

| For those patients treated at Pond Lane, daily

papers, library books and snooker and darts facilities improved the

lot of the in-house sick as did the Christmas visit by the local

pantomime cast. |

|

The cubicled ward of 10 beds that was opened

in 1928. Courtesy of Neil Fox.

|

|

The redoubtable figure of Matron Knox

Thomas and her group of senior sisters, most of whom spent the whole

of their working lives at the hospital reigned supreme. With the

introduction of the NHS in 1948 an infectious diseases block was

opened at New Cross, which had laboratory facilities and residential

doctors and a Chest Department. The ward and appropriate facilities

were thus seen as reducing the Parkfields operations. Added to these

factors the widespread immunisation polices adopted by Health

Authorities to curtail the Zymotic disease meant that the day of the

fever hospital was drawing to a close.

A reprieve against closure in 1976 lasted for

two years and a plan to create a day centre for mentally handicapped

patients came to nothing and finally in 1984 the hospital closed

thus ending 100 years of service to the community. The grounds of

Parkfields Hospital now compose a housing development. It is

interesting to note that as we entered the 21st century

the evidence of H.I.V., Hepatitis and Tuberculosis have become

dangerous realities.

In 1950 a single case of Smallpox recurred in

Bilston and a similar scare arose in Wolverhampton, but medical

controls were adequate and both cases came to nothing. Parkfields

was also known as ‘The Borough Hospital’ throughout its life.

Roy Stallard

T.D.

|

|

Return to

the

health section |

|