|

Beginnings

Prehistoric inhabitants

Sandwell Priory ruins in Sandwell

Valley Country Park were excavated by Dr Mike Hodder

between 1982 and 1987. His finds include prehistoric

artefacts that were made by prehistoric residents. The

finds include more than 800 worked flints, that were

made from local pebbles found in clay deposits and

shaped and sharpened for use as arrowheads, scrapers and

piercers, long before metal was used. Post holes were

discovered which suggested that temporary or permanent

dwellings were there. Burnt mounds were also discovered

that were carbon dated to 2,970BC, plus or minus 160

years. They were situated close to streams and could

have been used to heat water for cooking or for

primitive saunas and suggest that the settlement was a

permanent feature.

Roman Britain

Little is known about the Roman occupation of West

Bromwich. The excavations at Sandwell Priory revealed

some small pieces of Roman pottery, two Roman coins and

part of a Roman brooch that dates from 50 to 70AD.

There has been much speculation

about Roman Roads, which must have been in the area,

including the possibility that part of the main Holyhead

Road was originally Roman.

Traces of a

Roman road have been found at Bilston and Roman coins

from the first century were found at Wednesbury in 1817,

including examples from the reign of Nero, Vespasian,

and Trajan. Another Roman coin was found at Wood Green

during the excavation of the railway cutting, and a piece of

Roman glass came to light in Monway Field, Wednesbury. A Roman brooch was recently found at Aldridge

and other

Roman coins have been found in Bilston, Perry Barr,

Great Barr, Barr Beacon, and at Stonnall, near Walsall

Wood.

Anglo Saxons

Most of South Staffordshire and the

West Midlands was originally covered by forest, scrub

and marsh. Early colonisation started in the 6th century

when Anglo-Saxons came from France, The Netherlands,

Germany and Denmark.

Angles and Saxons first reached our

shores during the Roman occupation and were mentioned by

the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus who considered

them as barbarians, along with the Picts and Scots. He

mentions raids in 365, and the mid-fifth century, the Gallic

Chronicle records a large raid in 410 after the Roman

army had departed.

At this time there were frequent

raids by continental pirates and many towns employed

mercenary soldiers for protection. These soldiers were

Angles and Saxons from northern Germany who brought

their families with them and were given farmland as

payment for their services. Soon the mercenaries

realised that they were stronger than their employers

and so began to take over the running of many areas. The

Anglo-Saxons slowly colonised England, moving northwards

and westwards, pushing the native Celts into Cornwall,

Wales and Scotland. By 850AD there were three competing

kingdoms; Mercia, Northumbria and Wessex.

South Staffordshire was a part of

Mercia, which was derived from the old English word “Mierce”,

meaning people of the boundaries. The kingdom developed

from settlements in the upper Trent valley and was

colonised by a band of Angles called the Iclingas.

Slowly the area was populated and the kingdoms of the

Saxon and Angles in the midlands amalgamated to form the

kingdom of Mercia. In 913 Stafford became the capital of

Mercia after it had been fortified by Queen Aethelfaed.

In about the 8th century, a tribe

called the Anglian Mercens came from the north.

Initially they followed the Trent Valley, and began

spreading along the valleys of the Tame and its

tributaries. They were known as the Tomsaetan (dwellers

by the Tame), and would have settled here. There were

several natural advantages for them in this area, the

ready-made clearings, a good water supply from the local

brooks, and a slightly elevated position making the site

easily defendable.

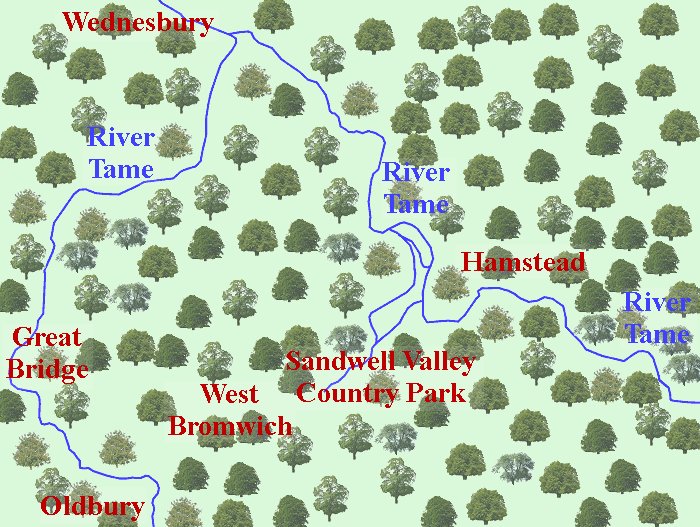

Cannock Forest and the River Tame.

Settlers moving into the area would

have found or made clearings in the woodland to build

their houses, keep their cattle and grow their crops.

Evidence for such clearings and settlements can be found

in many of the names of local towns. The old English

word “leah” means a woodland clearing and can be found

in some local place names:

Bentley, Brierley Hill, Coseley,

Cradley Heath, Dudley, Sedgley and of course the area in

Darlaston known as The Leys.

The old English word “halh” meaning

a pocket of land appears in Willenhall and the word

“tun” meaning a settlement is found in Bilston,

Wolverhampton and Darlaston.

There would have been a tiny

settlement in the West Bromwich area by the 8th century.

The area was known as ‘Bromwic’ meaning a settlement in

the broom. The open heathland in the area must have been

covered in broom. It was surrounded by part of Cannock

Forest, where the Mercian Kings hunted wild boar,

wolves, and possibly deer. Another surviving place name

from that time is Lyndon, which means a settlement in a

flax field.

|

|

| Read

about Anglo-Saxon England |

|

| |

|

| The

Norman Invasion The Normans were

descended from Vikings, who had settled in

Normandy, married into the local population

and adopted the French culture. It is

believed that in 1051 King Edward of England

named his distant relative, William Duke of

Normandy as his successor. So William had

claim to the English throne.

Edward died on the 5th January, 1066 and

on the following day, Harold was crowned as

the new king in Westminster Abbey. His

rivals to the throne had been William Duke

of Normandy and Harald Hardrada of Norway.

The Norman invasion had been expected and

so Harold made plans to defend the country.

The

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle claimed that by June

1066 Harold had gathered such a great naval

force, and a land force also, as no other

king in the land had gathered before. His

plans however, were thrown into

disarray when his estranged brother Tostig,

Earl of Northumbria and Harald Hardrada of

Norway led an invading army from the

northeast. |

|

A Harald Hardrada

coin. |

At the beginning of September, 1066,

Harald Hardrada's army raided Scarborough

and slaughtered most of its inhabitants. On

the 20th September, Hardrada and Tostig won

a battle at Fulford Gate and on the 24th

September they captured York.

Harold and his English

army travelled the 200 miles from London to

York and fought the invading army at

Stamford Bridge, on the 25th September. Both

Hardrada and Tostig were killed during the

battle and large numbers of their troops

were drowned in the River Derwent.

Harold heard that William of Normandy had

landed at Pevensey Bay on 28th September

with an invading army, possibly whilst

celebrating his victory in York. |

|

Harold and his troops quickly returned to

London, waiting there for about a week

before travelling south again. He had hoped

that some of the northern English troops

would join him there, but they didn't

materialise. Harold and his army marched

south and camped at Caldbec Hill,

just over 8 miles to the north west of

Hastings, on the night of the 13th October.

Harold and his 7,000 strong army were at a

great disadvantage because they were

suffering from the exertions of their

previous battle and the 240 mile long march

from the north.

Harold had taken a

defensive position at the top of Senlac

Hill, now called Battle. On the 14th

October, Harold and his army were defeated.

During the battle, Harold and many of his

troops were killed. The traditional account

of Harold dying from an arrow to the eye and

brain dates to the 1080s, but of course is

unproven. William was crowned in London on

Christmas day 1066. |

|

The image of the

wounded King Harold on the Bayeux Tapestry. |

After the invasion, the Normans

quickly gained control of the southern

part of the county, but were met with

hostility in the north and east. King

William initially had control of the old

kingdoms of Essex, Kent, Wessex, Sussex

and part of Mercia. Edwin Earl of Mercia

and his brother Morcar, Earl of

Northumbria, were delighted that William

had overthrown the Godwin family in

Wessex. They believed that he would be

satisfied with the territory he had

already gained and so would leave them

in control of their kingdoms. If they

had understood their true situation and

attacked William before he became

established, they may have been able to

overthrow him.

Three months after his coronation, King

William returned to France and took with

him the people who were most likely

cause trouble while he was away,

including Edwin and Morcar. During his

absence, unrest began to grow and there

was an attempted invasion by Eustace,

Count of Boulogne, who was Edward the

Confessor’s brother-in-law.William

hastily returned in December 1067 and

set about consolidating his hold on the

country. He took Exeter after an 18 day

siege and began to build castles at

important sites. His wife Matilda

arrived here in 1068 and was crowned

Queen. When he returned to Normandy in

1069, one of his most formidable

lieutenants, Robert de Commines, and 500

of his followers were slaughtered after

a drunken debauch in Durham. The Norman

castle at York was besieged and on the

king’s return he put down the rebellion

and sacked York. William was hated by

many of the English and more resistance

to his rule was to follow.

William and his army swept through

the northern counties from Shropshire to

Durham and the Scottish borders on a

mass killing spree. Villages were

burned, animals slaughtered, crops

destroyed and any survivors were left to

starve. This led to the deaths of over

100,000 people and effectively ended any

further resistance in this part of the

country.

A Danish fleet arrived off the

Northumbrian coast to lend support to

the general uprising. This was led by

King Swein who had as much claim to the

English throne as William, if not more.

He was the nephew of King Canute and was

joined by Edgar the Atheling who was the

main English claimant to the throne.

William managed to buy-off the Danes and

Edgar fled to Scotland. |

An engraving of a

silver penny from King William's reign. |

The final English revolt took place

in the fenlands of East Anglia in 1071.

Hereward the Wake led a number of raids

on the Normans from the safety of the

marshes around Ely. He was joined by

Earl Morcar, whose brother Edwin had

been murdered by his own men. William

sent troops into the marshes and

defeated the Saxons. Hereward escaped

but Morcar was captured and imprisoned.

William felt that he could not trust the

Saxons at all and the remaining Saxon

landowners had their lands confiscated

and given to trusted Normans. After 1066

most of Mercia still belonged to Earl

Edwin of Mercia, but after his death the

estates were divided amongst William’s

followers. Much of local Mercia

including Dudley was given to Ansculf of

Picuigny who built a motte and bailey

castle at Dudley. |

Under William the medieval feudal system

continued to be used. William owned all of

the land and divided it up into areas, which

were each ruled by a tenant in chief who was

one of his trusted barons. They each

controlled their area in return for payment

from taxes and supplied soldiers for the

king’s army. Each area was divided into

smaller areas (manors) that were controlled

by the baron’s knights, who were called

lesser or mesne tenants. They had to take an

oath of loyalty, carry out any required

duties and pay taxes for their land. Each

manor would include several villages whose

inhabitants were called peasants. There were

several classes of peasant. The highest was

a freeman who was free to pursue a trade.

The other classes were owned as part of the

land and were not free to move around.

They were villiens, bordars, cottars and

serfs. A villien offered agricultural

services to his lord, a bordar was a

smallholder who farmed on the edge of a

settlement, a cottar was a cottager and a

serf was an agricultural labourer. In return

the lord of the manor was supposed to

protect and help them. The other major

landowner was the church and bishops and

abbots could be tenants in chief or lesser

tenants.The original

Dudley Castle, a simple wooden motte and

bailey, was constructed in 1070 by Ansculf

de Picquigny, father of William Fitz-Ansculf,

who succeeded him. At this time the town

served as the seat of the extensive Barony

of Dudley, which possessed estates in eleven

different counties across England: Stafford,

Warwick, Worcester, Surrey, Berkshire,

Northampton, Buckinghamshire, Rutland,

Oxford, Middlesex and Huntingdon.

William Fitz-Ansculf was

in control of more than 80 manors, scattered

across several counties and like his father

was based at Dudley Castle. His holdings

included Amblecote, Aston, Birmingham,

Bushbury, Chasepool, Edgbaston, Enville,

Erdington, Essington, Great Barr, Handsworth,

Himley, Moseley, Newport Pagnell, Orton,

Oxley, Pendeford, Perry Barr, Sedgley,

Seisdon, Trysull, Upper Penn and Lower Penn,

West Bromwich, Witton and Wombourne.

As the country settled down under Norman

rule, William wanted to ensure that he

received all of the taxes that were owed to

him. This was very complex because the

country had been divided into a large number

of tax paying manors. The solution was the

Domesday Book and work on it began in 1085

when teams of investigators toured the

country. The information gathered from all

over the country was collated into the book

at Winchester and from this precise taxes

could be calculated. |

| When a team of investigators arrived in

an area they would meet with the landowner,

the local priest and a group of older

villagers. The information gathered was as

follows: The name of each tenant-in-chief,

tenant and under-tenant, the total amount of

land, the amount of land under cultivation,

the amount of woodland, the number of

people, animals and ploughs and any

fishponds or mills.

The Domesday Book was not completed until

after King William’s death on 9th September

1087. Today it is the most important source

of information about village life in the

Middle Ages. |

An engraving of the

reverse side of a silver penny from

William's reign. |

|