Chapter

Five Part Three

|

The Mention of Clarrie

Wise reminds me that like Sunbeam's George Dance he was not

really a road racing man. Clarrie's forte being trials. He was a

member of the A.J.S. team in many international events

collecting gold medals and silver cups galore.

Soon after the

Isle of Man races Jack Emerson had a brace of HRDs at

Brooklands, winning the 200 mile race at 84.27m.p.h. The

Italian Grand Prix fell to Achillie Varzi riding a

Sunbeam and the 350c.c. and 500c.c. classes of the

French Grand Prix fell to A.J.S.

Nearer home

again and to the Ulster Grand Prix, no longer a handicap

race. 1926 brought good results for Wolverhampton

machines for the first time Sunbeam’s Competitions

Manager Graham Walker won the 500c.c. race at

70.43m.p.h., also setting a record lap of 75m.p.h.

|

| Team mate Tommy Spann took second

place whilst Charlie Dodson claimed third spot in the

350c.c. race on his Sunbeam.

There were some changes to the 1926 Amateur T.T. The

race distance had been increased from 5 to 6 laps, a

distance now of 227 miles. Everyone enjoyed good weather

for the practice period but then came the rains and race

day dawned with roads awash and the dreaded mist on the

Mountain. The race proved a runaway for “A. Reserve”,

the non de plume of Rex Adams. He adopted it so that his

parents would not know he was racing until it was all

over.

Adams or “A.

Reserve” rode an A.J.S. and led by 28 seconds at the end

of the first lap. He increased his advantage on each lap

to finish 12 minutes 8 seconds ahead of M.I. Dawson’s

HRD. D. Oldroyd took 3rd place on a Sunbeam. The

winner’s time of 3 hours 52 minutes 23seconds at an

average speed of 58.46m.p.h. was a good performance in

the truly terrible weather conditions. The winner also

made the fastest lap of 61.76m.p.h.

Whilst the only

A.J.S. in the race had proved to be the winner, there

were numerous other Wolverhampton made machines in the

race. Riders of HRDs claimed 2nd, 9th and 21st places

and Sunbeams came 3rd, 5th, 10th, 11th, 12th, 13th, 17th

and 19th. All told it proved to be a very good race for

the riders of Wolverhampton made machines.

You may have noticed

that no mention has been made of Len Randles. It will be

remembered that he won the first two Amateur T.T.s and looked

like doing it again the following year until mechanical bothers

forced him out. He had also ridden very well in the June T.T.

Whilst returning from a trial he met with a serious road

accident and was badly injured. The injuries ended his racing

career, which was a great pity as he was a rider of tremendous

ability and could well have become a member of one of the

leading works teams.

|

| Before moving on to the year 1927

we shall look at something that might have been.

Although Villiers supplied engines in very large

quantities to many motorcycle manufacturers, both at

home and abroad, they were not to produce complete

machines. No doubt from time to time they considered

doing so, but perhaps felt it best not to compete with

their customers. All that is quite well known, but what

is not so well known is the fact that around 1926

Villiers considered producing a car. |

An advert from 1926. |

|

Leslie Farrar, nephew of

the Wolverhampton concerns Managing Director Frank Farrar left

his employment at the Austin Motor Company to work on the

project. A medium size six cylinder vehicle of good quality was

envisaged that would sell at a reasonable price.

Some experience

was gained by visits to factories in America, where it

was learned that mass produced engines could be supplied

at a very low prices, for example six cylinder engines

could be supplied at around £28 per unit.

In the event

three prototype cars were built and road tested and they

proved quite satisfactory, but the state of the industry

at that time caused Villiers to think again and the idea

was dropped.

|

| All was not lost however, for

Leslie Farrar stayed on and when his uncle retired he

took over as Managing Director and led the company to a

very successful future.

Now to 1927 and a look at Sunbeam. As noted above, cash

difficulties had curtailed the Wolverhampton factory’s

racing programme. Coatalen was still responsible for the

group’s competition activities. Talbots would still be

racing and Coatalen was keen to keep the Sunbeam name in

the limelight, and so he and his staff cast around for

ideas to accomplish this. Sunbeam had held the land

speed record three times and on the last occasion with a

12 cylinder 4 litre car pushing it to l53.33m.p.h. This

took place in March 1926 and was the first car to travel

over 150m.p.h. It had been driven by Henry Seagrave, but

a few weeks later the record was broken by Parry Thomas

at Pendine Sands. He reached 169.3m.p.h. and on the

following day, April 28th, he tried again and

increased his speed to over 170m.p.h.

Whilst the

Sunbeam and previous record cars had been quite

conventional racing cars Thomas's car “Babs” was very

special, being powered by a 27 litre Liberty aeroplane

engine. This heralded the end of the “ordinary” record

breaker, from now on they would be monsters.

Perry Thomas’s

record of 171.02m.p.h. stood until February 1927 when

Malcolm Campbell took his latest “Bluebird” to Pendine.

The car was powered by a 22 litre l2 cylinder 450h.p.

Napier “Lion” aeroplane engine and he pushed the record

to 174.8m.p.h.

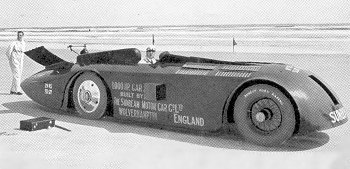

Whilst all this

had been going on a very special record breaker was

under construction at Sunbeam, and this was really a

monster. During the last months of 1926 Louis Coatalen

had decided to put the Sunbeam name forward to take the

land speed record again. Sunbeam had built the first car

to exceed 150m.p.h. and now the sights were on 200m.p.h.

This was a very ambitious plan but calculations had

shown that it could be done, if tyres could be made to

withstand such speeds. As so often Dunlop got down to it

and of course did produce suitable tyres. |

| The Sunbeam LSR car which became

known as the 1,000 h.p. had two ‘V’ 12, 22.5litre

435h.p. Sunbeam “Matabele” aeroplane engines. The design

had been sketched out by Coatalen and then handed over

to Captain Irving to develop. |

|

|

The engines had cylinder

dimensions of l22 x l60mm and were mounted one in front and one

behind the driver. They had two overhead camshafts to each bank

of six cylinders and there were eight BTH magnetos firing two

plugs per cylinder. The engines were fitted with four Claudel

carburettors and the car weighed 3.5 tons.

The starting

procedure was quite complicated. The rear mounted engine

was first started by compressed air and when running a

friction clutch engaged, coupling it to the front engine

and a positive dog clutch was engaged. There was a

geared up drive to a massive three speed gearbox and a

final drive to the rear wheels by side chains. The whole

chassis was enclosed in a streamlined body, the first of

its kind. For the record attempt the rear wheel covers

where removed to help cool the rear tyres. Though known

as the 1,000h.p., an excellent publicity figure gave the

actual power at around 870h.p. at 2,000r.p.m. |

|

A massive test rig had

been constructed in the experimental department at the Moorfield

Road works and tests proved satisfactory. The question now arose

of a suitable venue for the attempt, as both Pendine and

Southport were considered unsuitable. After a lot of discussion

the choice finally fell on Daytona Beach, situated in Florida.

This had been the choice of Henry Seagrave who would be driving

the car.

|

|

The car and personnel

travelled on the “Berengaria” and during the voyage they heard

the tragic news that Parry Thomas had been killed whilst making

a record attempt at Pendine. This could have been disturbing for

the Sunbeam party as it was reported that the accident had been

caused by the breakage of a driving chain. The Sunbeam also had

chain drive, but on “Babs” the chains were only protected by a

thin metal cover, whereas on the Sunbeam they were enclosed in

armoured cases. None the less prior to the record attempt they

were very thoroughly inspected, and incidentally when on the

test rig at the works the chains had run red hot.

The team arrived in

America and travelled directly to Daytona where the record

attempt was due to be made on March 20th. At about

10a.m. Seagrave started on his first run and what a thrilling

sight it must have been as the great red car streaked down the

course with its driver only just able to keep it under control.

At the end of the run all the tyres were changed and the car

started back again with Seagrave fighting for control. It had

been a most successful run. The flying kilo had been covered at

202.988m.p.h., the flying mile was at 203.792m.p.h. and the

flying 5 kilometres was achieved at a record speed of

202.675m.p.h. Thus beating the previous record by no less than

28m.p.h., the greatest margin of increase to date. Seagrave went

down in history as the first man to travel at over 200m.p.h. on

land, a very fine and wonderful achievement.

There were many

congratulatory telegrams and messages, one of which came from

Malcolm Campbell, the previous record holder, who was now well

prepared to have another attempt. This he did in 1928 and took

the record by a little over 3m.p.h. Sad to say Sunbeam would not

again hold the record, but happily the car still exists. Louis

Coatalen had wished to gain world wide publicity at little cost,

and this he had done. The car had cost around £5,400 including

labour, most of the expenses of the American trip having been

met by the component manufacturers and sponsors. It had all been

achieved at a fraction of the cost of running a Grand Prix

racing team.

With Sunbeam’s racing

activities curtailed the Wolverhampton cars were not seen in the

big international events, none the less they still featured in

many home events. At Brooklands Kaye Don notched up a number of

successes. In the six hour race three of the 3 litre sports cars

were entered. They were driven by Henry Seagrave, George Duller

and J.W. Jackson/N.Turner. Duller won the race having covered

386 miles. Seagrave retired but the other Sunbeam finished 6th.

At the September Shelsley Walsh Hill Climb the famous mechanic

Bill Perkins took 2nd place in the 2 litre class, driving a 2

litre supercharged six cylinder car and then with the ‘V’ 12

supercharged 4 litre, won the over 3 litre class. |

|

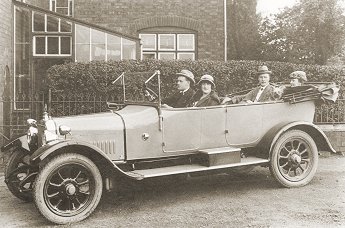

A 1921 Sunbeam 6h.p. tourer. |

For 1927 Sunbeam offered a fine

range of 6 models, all of which had overhead valve

engines. Prices ranged from £550 for the 16h.p. to £1975

for the luxury straight eight 45h.p. car. These

Wolverhampton made cars were among the very best made,

indeed it can be said that the quality was far to good

for the prices asked. Very great care was taken in

manufacture and testing, for example crankshafts were

turned from solid billets of special high grade steel

and gears were ground both sides and then meticulously

tested.

|

| All this cost money, but no one

in charge at Moorfield Road seemed keen to grasp the

nettle and increase prices or try to introduce more

efficient work methods. The former solution would no

doubt have badly effected sales, but it should have been

possible to have organised more economic production

without in any way impairing the quality of the product.

It is a great pity something was not done, for there was

a ready market for all that Sunbeam could produce.

The Star Motor Company were also able to sell all the

cars and commercials produced at the Frederick Street

works, though in much smaller numbers than Sunbeam. More

buildings were being erected at the Bushbury site with a

view to an early move there for all production. During

1927 a number of cars were supplied to King Ibn Saud

including some Harem cars. Also during the year

cellulose finishes were introduced.

The cars offered by Star

included a four seater tourer, with a four cylinder 11.9h.p. ohv

engine and cylinder dimensions of 69 x l30mm. It sold

£4l0. The l8/50 five seater saloon, fitted with a 17.9h.p., six

cylinder ohv, 75mm y 120mm engine cost £850.

For sometime Star had

named their various models after stars, for example the 14/40

side valve four cylinder, two seater was the "Argo" and cost

£410. The "Draco" a five seater tourer was listed at £425 and a

saloon version the "Dorado" cost £475. The cars all shared a

common chassis and engine.

Quite a lot of publicity was made

of the fact that the well known tropical explorer Mrs.

Diana Strickland was to drive a car across Africa at its

widest part and that the car chosen would be a Star. She

left Wolverhampton during May with a 14/40 named "Star

of the Desert”. It was a standard vehicle except that

the body had been fitted out to give some sleeping

accommodation. Mrs. Strickland's journey proved to be a

success having covered 7,236miles over some of the

wildest country in Africa in a running time of 58 days,

though she was away for little over a year. |

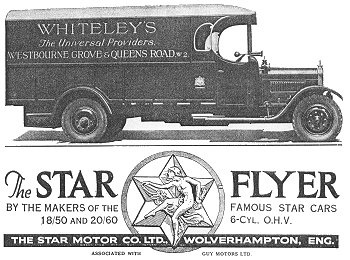

| Turning now to Star commercial

vehicles we note that the “Flyer" was introduced. It had

a 24h.p. ohv six cylinder engine with cylinder

dimensions of 80 x 120mm and was said to be the first

overhead valve six to be fitted into a British

commercial vehicle.

Designed to take 20 seater coach

bodywork, it was said to be faster than some of the

cars. During the last three months of 1927, 105 cars and

5 commercials were sent out. |

|

| Staying with the commercials, Guy

Motors were being kept busy producing a fine range of

lorries and passenger service vehicles. A forward

control version of their six wheel double deck bus came

out and found many customers, one becoming the first six

wheeled bus to operate in London. A rather out of the

rut vehicle that Guy introduced during 1927 was the

produced gas lorry. The idea was to use the vehicle in

countries where petrol was in short supply and

expensive. Producer gas vehicles were used in limited

numbers during the two world wars and various solid

fuels could be used. In the 1927 Guy system charcoal was

the fuel, but it is recorded that one large British

municipality ran a fleet of Guys on sewer gas. This must

have been a great saving for the rate payers. Quite a

number of the producer gas vehicles were sold and the

customers included the Australian Government and the

Crown Agents for the Colonies. |

|

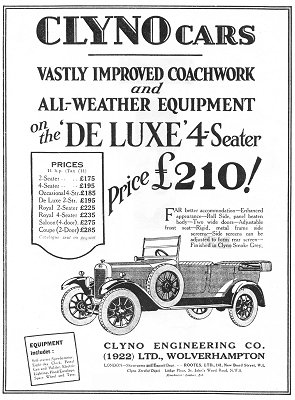

Nothing has been said

about Clyno for sometime. This is not to say that nothing was

happening at the Pelham Street works. On the contrary they were

very busy, and whilst the larger Clyno, a competitor to the

Morris Oxford was not doing too well, a smaller model was a

serious competitor for the Morris Cowley.

A fully equipped

four seater saloon now cost £200, which was very good

value. Production stood at around 300 cars per week,

making the Wolverhampton concern the third largest motor

manufacturer in the country. It really is a marvel

how they managed such production in the rather cramped

Pelham Street works. A move to larger premises was afoot

and at the beginning of 1927 Clyno moved to a large new

factory at Bushbury, premises that would later be

occupied by Britool. As well as cars an 8cwt Van was

brought out to sell at £173 and proved quite a success.

|

|

As with their

motorcycles Clyno did not enter cars in speed events. In 1924

they had produced a very nice sports model which had a polished

outside exhaust system and very attractive Swallow bodywork. The

demand for the other models was such that only few of the sports

cars were built.

Clyno did support

reliability trials, often with Frank Smith at the wheel. Jimmy

Crocker also drove in the works team and they enjoyed many

successes as did numerous private owners who entered the various

competitions. |

|

|

|

Return to

Part 2 |

Return to

the beginning |

Proceed to

Part 4 |

|