Employment

| As my hopes of being a teacher had long been

extinguished, I sought other means of earning a living. An

advertisement in the local evening paper, the 'Express & Star',

stated that by sitting an examination and passing with good marks, I

could attend a commercial college and train for work as a secretary.

In due course I enrolled as a day student at the 'M.P. Commercial

College' which was on the 4th floor of the Royal London Buildings in

Princes Square, Wolverhampton. I went five days a week, from 9-00am

to 5-00pm. There I studied Pitman's Shorthand, typing, bookkeeping,

office routines and English. Reaching good standards in these

subjects, I received certificates of merit for my various grades,

including one for achieving 100 words a minute in Pitman's

Shorthand. |

|

Mollie. |

I enjoyed my time at college, but should point out that I was trained

free of charge, only on the condition that half my salary for the first

two years must be paid to the college. My first week's pay was 7/6d

(37.5p. in today's money). While I was at college, I was sent for

practice to a butcher's shop in Fallings Park. I worked in a tiny

box-like office at the far end of the shop where customers paid for

their purchases. When the shop closed on Saturday I saw parcels of meat

had been put out along with the wage packets, but nobody told me one was

for me. The second week, a joint of meat was handed to me with my 2/6d.

pay. I worked at that butcher's for a month and the experience, and the

joints were very helpful.

Further experience was acquired when I was sent as a temp. to a firm in

St John's Square. This was a foundry owned by two brothers, C & B Smith.

The office was equipped with a very old typewriter, the 'Olivet

Invisible', on which you could not see the words you had just typed. Oh

dear, how many errors had I made?

|

|

My first job after leaving college was at John Shaw & Sons, in Fryer

Street, Wolverhampton. It was a firm of Factors, and I was engaged as a

junior clerk for the sum of ten shillings a week. I had to answer the

telephone and do the filing, as well as other duties, which included

fetching coal and wood from the cellar for the open fire. This last task

MUST NOT be undertaken alone in case a man followed with evil intent!

Orders came over the telephone in code and it was my job to decode the

messages, type the orders out, show them to my boss, then take the order

to the right department for the goods ordered. The office hours were

8-30a.m. to 5-30p.m. on Monday to Friday and 8-30a.m. to 12-30p.m. on

Saturdays. I had one hour off for lunch. The holidays were Christmas Day

and Boxing Day, Good Friday and Easter Monday, and Bank Holidays. There

was no annual holiday entitlement until you had been with the firm for

12 months, then you could have one weeks holiday without pay. Providing

that no more senior members of staff wanted the same week.

|

Mollie. |

|

My mom, Mary Ethel Rendell. |

Once, when Dad was in hospital and money was tight, I plucked up

courage to ask for a rise. My boss arranged for me to go before the

Board. With trepidation, I appeared before the 12 elderly gentlemen and

put my case. They expressed sympathy over my father's illness, but said

that consideration was being given to reducing the number of staff, and

as I was last in, I would be first out! So no raise!

I had told Dad I wanted to leave this company, but he said I must

remain where I was, for at least a year in order to get a reference. In

those days a reference would not be given for anyone with less than

twelve month's service.

My next job was as a junior in the offices of Reginald Tildesley, a

Ford Motor dealers in Willenhall. I travelled there by train and

returned home for lunch each day. Mom always had it ready as I walked

in. Then I ran back to the station, on to the train, and back to the

office, all in just over an hour.

|

|

My job was to take the money for petrol and small spares. I registered

the details on a roll on the till, pressed a button on the cash machine,

and the drawer containing cash flew open. At the end of the day I had to

add up all the items on the till roll and check the money. It had to

tally.

There were a lot of mechanics, sales representatives and office staff

at the company. But Mr. Tildesley was always around and knew all his

staff. On the occasion of his Silver Wedding anniversary, he gave us all

a splendid party. The big garage building was transformed, decorated

with flags and balloons, and a splendid meal provided. This was followed

by the showing of photographic slides of his overseas holidays. I was

very excited by this event as Mom bought me my first evening dress. It

was a lovely pale primrose silk with three flounces round the long

skirt. The mechanics were also transformed, wearing evening suits and

crisp white shirts. There were speeches and votes of thanks, and a gift

was made to Mr. and Mrs. Tildesley.

|

| Mr. Tildesley's mother lived in a big house adjacent

to the garage. She was a widow and lived alone. Reginald Tildesley,

his wife, and their two daughters lived in a spacious bungalow

further along the road. On occasions, Mr. Tildesley asked me to do

some shopping for his mother, which made a change from office

duties. I remember the thrill of her telling me about her visit to

the Oberammagau Passion Play in Austria. I secretly decided that one

day I would make the trip. |

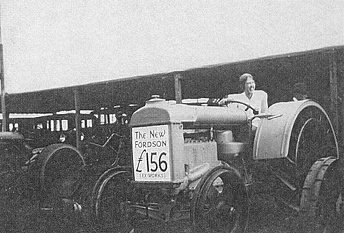

Mollie at the Royal Show while working for

Tildesley's. |

|

With the onset of the Second World War the performance of the play was

suspended. It was normally held every ten years. However, my secret

dream came true in 1970, when, with my friend Doris North, we joined a

party of fellow Methodists and went to see the Passion Play in Austria.

While working at the garage I joined the amateur dramatic society at

the Methodist Church in Union Street, Willenhall. I went to rehearsals

one evening a week and then went back to the home of a fellow member,

whose father was Station Master at Willenhall. Many times my sleep was

interrupted, as a train appeared to be roaring right through my bedroom.

I enjoyed being in the chorus of 'A Country Girl' and 'The Belle of New

York'. On Saturday nights at the end of the run, bouquets were presented

to the principals, and friends and relatives gave flowers to the rest of

the cast.

|

|

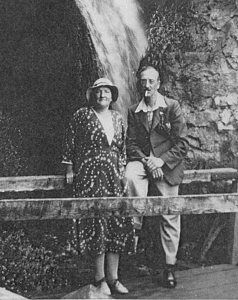

Mom and Dad at Rhyl, 1st Sept.1939. |

When I felt it was time to move on and become a

secretary instead of a junior clerk, I answered an advert in the

'Express & Star' for such a position. I was invited to attend for

interview at a big private house in Compton Road. I was shown into a

delightful room, by a tall, slim lady, and she introduced me to a

very old gentleman (her father), who was sitting in an armchair. He

rose and extended a hand to greet me. He then dictated a business

letter to me, which I took down in shorthand and transcribed onto

the paper provided. To get it correct was a miracle, because while

he was dictating, my glance strayed to a window where tiny blue tits

were performing acrobatics on a coconut, hanging from the branch of

a tree. I was a 'townie' and had never before seen such antics,

though I recognised the birds from pictures in books. |

|

I got the job, and on the set date, I arrived at the offices of 'R. D.

Hadley & Co'. Only when Mr. Hadley (who had interviewed me) arrived did

I realise he was totally blind. He had a splendid memory and was fully

aware of everything to do with the business, which was as a 'middleman'

between 'Thos. Clatwin & Co', makers of iron grates, and their

customers.

Mr. Hadley employed a poor, elderly black man who did all the menial

tasks, including taking Mr. Hadley to the toilet. On one occasion Mr.

Hadley dropped his gold watch down the lavatory and 'Sambo' had to

retrieve it. The old man, chain-smoked cigars and 'Sambo' was called to

extinguish small fires started by Mr. Hadley's dropped ash or lighted

matches.

My next move was to the 'Wulfruna Coal Company' in Horseley Fields,

Wolverhampton. I became secretary to the owner of the company, Major

Alex Wood, who lived at Faintree Manor, a large country estate near

Bridgnorth. The Major, granting me an interview, to be held at the

Territorial Army Headquarters, answered my application for the post. I

was then aged about 19 and held very strong pacifist views. I rehearsed

what I might say, before Major Wood asked me to sit down. Politely, I

said 'May I say that I do not wish to be employed for a job that has

anything to do with war.' The Major replied, 'I am pleased to meet

someone with principles, who is prepared to stand by them, even if it

means losing the chance of a job. You are just the young lady I am

looking for.'

|

|

Major Wood assured me that I would be dealing only with the coal

business and that the Territorial Army was his personal and private

interest. I worked happily at Wulfruna Coal, along with a lady book

keeper, and a manager who was in charge of the lorry drivers and

boatmen.

The office was modern and situated on the wharf overlooking the canal

basin. Horses were stabled in the yard. They were lovely creatures,

which had become too old to race. They were intelligent and sure-footed.

A necessity when pulling barges along narrow towpaths. The boatmen were

hardy, swarthy fellows, who took barges to and from collieries at

Stafford and Lichfield etc. I believe some of the boatmen could be

described as 'honest rogues'. They did not actually steal coal, it just

dropped off the barge at a place where it could be easily retrieved

during the hours of darkness.

|

My wedding day. 13th April 1936. |

|

Deliveries of various grades of coal were made to houses and

businesses. The lorries were carefully checked before leaving the wharf,

so that we could be sure the correct number of sacks were on board. But

if there were any complaints about fewer sacks being received than paid

for, the drivers made excuses for the difference. Sacks not properly

checked at the wharf, householder had miscounted etc. etc.

During July and August, coal prices were considerably reduced for

customers who would take a complete load. Owners of large estates filled

their stores to capacity. And when did they pay for it? When coal was

reduced again the following summer, when a repeat order was given.

Each morning during the winter, a poor, bedraggled woman came to the

wharf with a little wooden hand cart and paid cash for a quarter of a

hundredweight of the cheapest coal. She lived in a

slum house nearby and had a lot of children. This worried me, but I

could not convince the manager that there should not be one rule for the

rich and another for the poor. So the rich got richer and the poor got

poorer.

After a 'shoot' on his Faintree Estate, Major Wood sometimes brought

surplus 'victims' to the office and sold them to employees. Two pigeons

for 1/-, rabbits 1/- each, a brace of pheasant for 5/-. I used to buy

some of them and our menus at home became more varied, especially with

Mother's good cooking.

|

|

My wedding. |

In 1936 one did not have to give notice to leave a job if you were

getting married. You just informed the boss of the date of the wedding

and you were given a leaving present, and left.

I left the Wulfruna Coal Company at the end of March 1936, two weeks

before my marriage on 13th April to Victor William Cox at Beckminster

Methodist Church in Wolverhampton.

|

|

|

|

| Return to

Washing and haircuts |

|

Return to the

beginning |

|