|

|

|

The Thorneycroft family (originally

Thornicroft) originated in Cheshire in the 13th century. In

the 1660s John and Katherine Thornicroft moved to Broseley,

Shropshire, where their son John was born in 1663.

John’s grandson, Edward Thorneycroft

married Mary Bradley, and they had a daughter, Maria, born

in 1787. Around 1790 they moved to Tipton, Staffordshire,

where Edward became landlord of ‘The Three Furnaces’ public

house. Their next two children, twin boys, Edward Charles,

and George Benjamin, were born there on 20th August, 1791.

They went to a local school, but George had little interest

in class work, and only learned to read because his mother

made him read the bible. His main interests were anything to

do with mechanics, or chemistry. At night he would go into a

nearby iron works and became fascinated with everything that

he saw, learning many processes that would be useful to him

in future years.

The family moved to Kirkstall, Leeds

where Edward senior worked at Kirkstall Forge. He was soon

joined by his twin sons who began their working life at the

forge, and attended evening classes to learn about iron

manufacture. George began to put to good use many of the

things that he had learned from his night-time visits to the

Tipton iron works.

In 1809 at the age of 18, the two

brothers returned to Staffordshire. George became an iron

puddler at Addenbrooke’s Moorcroft Ironworks at Bradley, and

soon discovered a method of producing better quality iron at

a cheaper price. Mr. Addenbrooke was delighted. He promoted

George to superintendent of the works, and gave him a share

of the profits. It was in this role that he established his

abilities as a confident leader.

After about two years he saved £600, a

lot of money at the time, and married Eleanor Page, daughter

of Thomas and Hannah Page, of Moxley. In 1817 he invested

his savings, along with Eleanor’s £300 dowry, in a small

ironworks that he opened at Forge Yard, Waterglade Street,

Willenhall.

George, Eleanor, and their first

daughter, Ann, who was 12 months old, moved to

Willenhall and lived in a cottage that stood on the site of

the HSBC bank, on the corner of New Road and Market Place.

It was here that their next four children were born; Mary in

1818, John in 1820, Emma in 1821, and Thomas (later known as

Colonel Tom Thorneycroft of Tettenhall Towers) in 1822. The

ironworks was unsuccessful and so George began dealing in

pig iron, and became wealthy on the proceeds. In his early

years George was a staunch Wesleyan Methodist, who later

joined the Church of England, and gave generously to

Willenhall Chapel. |

The HSBC Bank in Willenhall which

stands on the site of the Thorneycroft family's cottage. |

In 1824 he invested £1,800 in a new

venture with his brother Edward, and established the

Shrubbery Iron Works, in Lower Walsall Street,

Wolverhampton.

The works were in two halves with Lower

Walsall Street in the middle, and the Birmingham Canal

running alongside.

All of the chimneys were confined to

the northern half of the works between Lower Walsall Street

and Horseley Fields, so the iron must have been produced and

worked there. |

| In the beginning the works were quite small, producing

about 10 tons of iron each week, but thanks to George’s

expertise the business soon grew.

In a short while the output increased to between 600 and

700 tons a week, and the iron works became well known as

producers of high quality iron.

The two brothers worked together for several years, but

eventually they dissolved the partnership by mutual consent,

and Edward departed.

George continued to run Shrubbery Ironworks under his

company, G.B. Thorneycroft & Company. In later years his

partners were John Hartley, Thomas

Thorneycroft, John Perks, and Thomas Thorneycroft Kesteven.

The company also owned Bradley Colliery, the small

Millfields Ironworks at Bilston, and Dyer’s Hall Wharf in

London. |

George Benjamin Thorneycroft. |

|

In the late 1830s and early 1840s

railway mania swept through the country. As a result the

demand rapidly grew for rails and railway ironwork. George

Thorneycroft wrote to the newly formed railway companies

suggesting that all rails should be tested, and that many

manufacturers were supplying inferior materials. As a result

the ironworks received many orders from the railways and

became known as a supplier of high quality axles. |

|

George, later in life. |

George owned a number of coal mines,

and nearly lost his life in one of them. In December 1845 a

new pumping engine was being installed at one of his pits in

Willenhall. Unfortunately the safety valve was faulty, and

the boiler exploded, killing one man, and seriously injuring

sixteen others. George was amongst the sixteen casualties.

On regaining consciousness his first words were “Praise the

Lord O my soul.” Followed by “Who else was hurt?”

One year later, with his doctor, Mr. E.

Coleman, he presented himself before lecturing staff and

students at Queen’s College, Birmingham to demonstrate how

the severe burns covering much of his body, had been healed

by the use of cotton wool freely applied to the dressings.

George, a keen Conservative, was one of

the two guests of honour at the first Conservative

Association dinner which was held at the Star & Garter in

Wolverhampton. The other principal guest was Lord Ingestre. |

|

George became Wolverhampton’s first

mayor after the town’s incorporation in 1848. There were two

candidates, George, and John Barker, the ironmaster at

Chillington Ironworks. They were from rival political

parties, but good friends. After an amicable discussion John

Barker withdrew, and George became mayor.

He decided to give a mace to the new

corporation, and purchased the silver mace from St. Mawes in

Cornwall, which he found at Fown and Emmanuel’s

establishment in London. The mace had been in use until 1832

when the borough of St. Mawes was abolished by the Great

Reform Act. The mace is still the Wolverhampton mace today.

In 1850 George laid the foundation

stone of the exchange building that stood in Exchange Street

opposite the retail market. He was a wealthy and generous

man who eagerly contributed to many organisations and

charities. During his time as mayor he founded the

Thorneycroft Benefaction which consisted of a gift of £1,000

to be used for the distribution of blankets and flannel for

the poor. He contributed handsomely to the restoration of

St. Peter’s Church, and became a church warden. He laid the

foundation stone at St. Matthew’s Church, and paid for the

steeple at St. Mark’s Church. He also contributed £500 to

the Wesleyan Centenary Fund having been involved in the

Wesleyan church in his early life. On Sunday mornings he

worshipped at St. Peter’s, and on Sunday evenings attended

the Wesleyan Chapel in Darlington Street. His wife Eleanor

also supported the Wesleyan cause. In 1839 she assisted in

the ceremony for the laying of the first brick at Blakenhall

Wesleyan Chapel.

George was a benefactor to the South

Staffordshire General Hospital and Dispensary which opened

in Cleveland Road on 1st January 1849 (later known as the

Royal Hospital). The site was chosen, partly because of its

close proximity to the large factories, where accidents

often occurred. When the project began, George attended a

fund raising meeting, rose to his feet and said “I see an

old friend of mine in the room (William Ward). I challenge

him to meet my £500 with his, to give the concern a fair

start.” |

|

George was a big man, a plain speaker,

who spoke his mind. He had no airs or graces, but had a good

brain and could quickly get to the bottom of a problem. On

one occasion it was mentioned that some padlocks made

locally would only lock once, he instantly responded with

the following retort “As they had been bought at twopence

each, it would be a shame if they did lock twice.”

His political views were not always

welcomed. The first annual dinner of the Bilston Operative

Society was held on 7th August, 1840 in a marquee,

especially erected for the occasion in Bilston Market Hall.

The guests included George and a number of other prominent

conservatives. While the meeting was in progress, a large

number of people assembled outside the market gates, and

forced their way into the market. They stormed the marquee,

and roughly handled the diners, who were forcibly removed.

Their views were clearly not welcome in the town.

George served as a Justice of the Peace

for Staffordshire and Shropshire. It was said that his

judgements as a magistrate were firm and upright, and

dictated by plain common sense. He also acted as a mediator

between litigants, to avoid the necessity of resorting to

legal proceedings. |

George in his later years. |

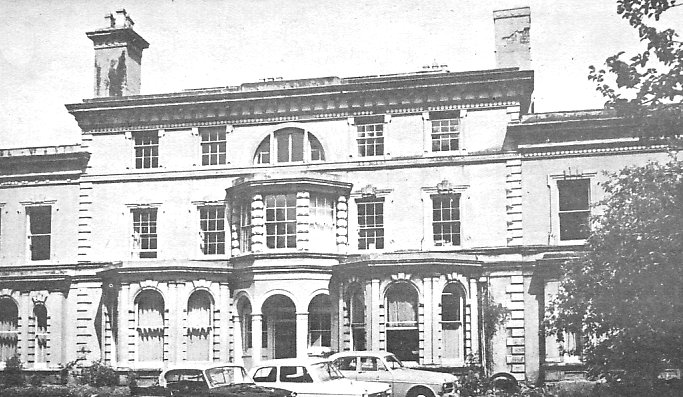

The Thorneycroft family's Wolverhampton home,

Chapel House, on Tettenhall Road.

|

George was a very happy family man, who

once said of Eleanor, his wife “I am indebted to providence

for one of the best women ever made, and blessed with a

family of children who are all I could wish.” They had two

sons and seven daughters, but sadly four of the children

died young. The children were as follows:

| Ann |

|

born in Willenhall in 1816, died 1822 |

| Mary |

|

born in Willenhall in 1818 |

| John

|

|

born in Willenhall in 1820, died young |

| Emma

|

|

born in Willenhall in 1821 |

| Thomas

|

|

born in Willenhall in 1822 |

| Ann

Maria |

|

born in Wolverhampton in 1825, died 1836 |

| Harriet |

|

born in Wolverhampton in 1827 |

| Ellen |

|

born in Wolverhampton in 1830 |

| Hannah

|

|

born in Wolverhampton in 1833, died young |

In Wolverhampton the family lived in

style at Chapel House, on Tettenhall Road. A wing was added

on either side, and it was later divided into two to form

Granville House and Salisbury House. As the children got

older, George built ‘Summerfield’ in the grounds of Chapel

House as a home for Mary. After her marriage, Emma and Ellen

began their married life there. The four girls married men

who became prominent in the town.

Mary married Charles Corser a

Wolverhampton solicitor.

Emma married John Hartley in 1839. He

hailed from Scotland and owned Hartley's Glassworks in

Sunderland. He moved to Wolverhampton, and in 1828 became a

partner in Chance Glass Works, Smethwick, with Robert Lucas

Chance. He was also a partner in G.B. Thorneycroft &

Company, and became a very wealthy man. When George died the

Hartleys inherited his estate in Wheaton Aston. They added

to the estate by buying more and more property, and then

sought a grander residence as befitting their new status as

landed gentry. In 1858 John and Emma leased Tong Castle from

the Earl of Bradford, and until his death in 1884, Hartley

was referred to as the Squire.

Harriet married Charles Perry,

the eldest son of Thomas Perry who founded Thomas Perry &

Son Limited at Highfield Works, Bilston.

Ellen married Henry Hartley

Fowler who trained as a solicitor, and came to Wolverhampton

as a partner to Charles Corser. He was elected to the

Council as member for St. Matthew’s Ward, and became mayor

in 1862/3. He then stood for Parliament and was elected with

a large majority. Because of his support for the

Wolverhampton Corporation Act of 1891 he was made a freeman

of the Borough in 1892. In 1908 he was raised to the peerage

as Viscount Wolverhampton.

Thomas, the most well-known of

the children, married Jane Whitelaw. He became a wealthy

industrialist, a landowner, and a well-known

Conservative. He was known as Colonel Thorneycroft because

he was a Lieutenant Colonel in the Staffordshire Yeomanry.

He is remembered for his wonderful home, Tettenhall Towers,

now part of Tettenhall College, and for his flamboyant

lifestyle, his inventions, and eccentricities.

In 1850 George purchased the old

Molineux estate in Willenhall, and in 1851 gave the land for

Wood Street Cemetery in Willenhall to the Methodist church.

The cemetery soon filled and no further interments were

allowed, except in existing graves. He also acquired a large

estate in Wheaton Aston.

George became an authority on the

manufacture of malleable iron, and on railway wheels and

axles. In 1850 he became an associate member of the

Institute of Civil Engineers, and gave a paper to them

entitled 'On the manufacture of Malleable Iron and the

Strength of Railway Axles'. For this work he was awarded the

Telford Medal.

George Thorneycroft

never recovered from the effects of the boiler explosion in

Willenhall. As time progressed he grew weaker, eventually

becoming bedridden. In the early part of 1851 he

suffered from brain disease, and appeared to improve, but a

relapse took place, and he died on 28th

April, 1851, at the age of 60.

He had a massive

funeral. The streets must have been lined with people, all

the way from the town centre to the church and the cemetery.

Around 20,000 people came to view the proceedings and pay

their last respects. Shops and businesses in Wolverhampton

closed between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m. The corporation was

entertained for lunch by Charles Corser, before they led a

long procession through the town, which included one

thousand of George’s workmen, many of his fellow

ironmasters, and his private carriage, which had the blinds

drawn, and was driven by Thomas Spilsbury, George’s

favourite servant.

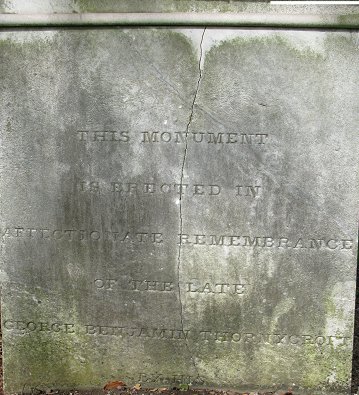

The funeral service

took place at St. Mark’s Church, and George was buried in

Merridale Cemetery. After his death around 1,000

Shrubbery workers subscribed to a bronzed cast-iron

monument, erected in the cemetery, to commemorate the life

of a well-respected employer. A colossal marble statue of

George Benjamin Thorneycroft produced by the sculptor,

Thomas Thorneycroft of London, was erected on a plinth next

to the grave. It must have been an impressive sight.

Although the plinth still remains, the cast iron monument

has gone, and the statue was moved to the entrance hall of

the new Town Hall in 1871.

When Eleanor died on 5th January, 1874

she was buried alongside her late husband. One other member

of the family is also in the grave. It is their daughter

Mary Corser who died on 18th December, 1897 at the age of

80.

Shortly after his death

George was honoured at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

G.B. Thorneycroft & Company received a prize medal for their

exhibit of Brigg’s patent compound axle, tyre, and rails. |

George, Eleanor, and Mary's grave in Merridale

Cemetery.

|

|

|

|

Two views of

the back of the grave which displays the family

crest, and George's name. |

|

|

|

|

|

Another two

views of the grave. |

|

|

On the side of the grave is the

following inscription that was added by Wolverhampton

Council:

In compliance with

the unanimous

request of the

Town Council of

Wolverhampton the

statue originally

erected on this

monument

was removed to the

Town Hall

on the 19th October

1871. |

|

Return to the

previous page |

|

|