| Matthew Biggar Walker

(1873-1950): Wolverhampton friend of Sir Frank Brangwyn

and patron of artists and arts |

| It is well known in Wolverhampton that the Art

Gallery and its collection were established as a result

of efforts and generous donations undertaken by several

local entrepreneurs and benefactors of the Victorian

period, such as Sidney Cartwright and his wife Maria

Christiana, Philip Horsman and Paul Lutz. Local art

patrons of the 20th century and their

involvement in the further development of the collection

are less known. Nevertheless, their influence appears

equally important to that of these predecessors. Their

efforts brought to Wolverhampton a strong collection of

works by 20th century artists and secured

their relations with the Gallery. One of such patrons

whose efforts helped to establish the national

reputation of Wolverhampton Art Gallery was Matthew

Biggar Walker (1873-1950). Son of a travelling draper,

he was born in Dudley, and started his career as a

school teacher. He moved to Wolverhampton by 1900, when

he married Ada Frances Boulton (1870-1953), a daughter

of a local butcher. Somehow surprisingly, he initially

established himself here as a tailor and draper on his

own account[1],

but very soon returned to teaching and eventually became

a superintendent of night classes at Queen Street Chapel

and a Sunday school teacher at Red Cross-Street school.

From 1910 and until their death, Matthew and Ada Walker

lived permanently in 1, Park Crescent.[2]

|

Donated by M. B.

Walker to WAG in 1919:

Frank Short.

Vessel in Distress (after JMW Turner). |

He developed a strong interest in art and

established close relations with many living artists of

the Black Country, such as Frank Short, Sidney Causer,

William Strang and Albert Goodwin.

In the 1910s-1920s Walker became known as an art

collector and art dealer.[3]

His name was first recorded in the Gallery’s acquisition

book in 1919, when he donated two works on paper by

Frank Short. |

| In November 1922

Walker was appointed a member of the Art Gallery and

Public Library Committee[4]

and for decades he remained its active member, loaning

works from his own collection to the exhibitions at the

Gallery, organising loans and donations from other local

collectors, communicating with artists and their

families, establishing links with museums and galleries

across the region. |

Donated

by M. B. Walker to WAG in 1919:

Frank Short. The

Landscape. |

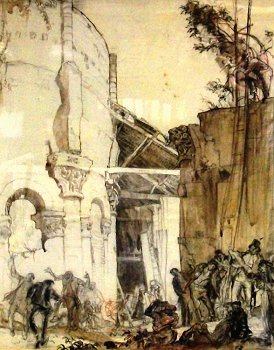

| In 1924, he donated six drawings by Edward Poynter

to Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, thus it is not

surprising that next year, when Walker organised in

Wolverhampton the Albert Goodwin (1845-1932) exhibition,

its formal opening was performed by Sir Whitworth

Wallis, the first director of BM & AG and son of

George Wallis of

Wolverhampton. The exhibition included ninety one

artworks and was described as ‘the largest and the

most representative collection so far.’ Sir

Whitworth said that Albert Goodwin was a master of many

methods, and that was the finest exhibition of his works

he had seen[5].

|

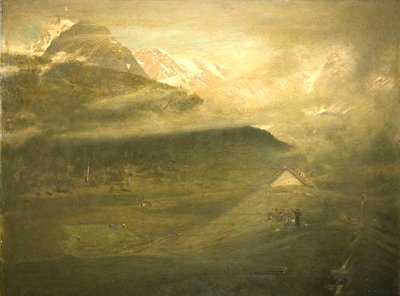

Donated

by M. B. Walker in 1925: Albert Goodwin. Sermon in the Hayfield. Simplon. 1882. |

Walker loaned for that exhibition two Goodwin

paintings from his own collection. One of these, ‘Sermon

in the Hayfield, Simplon’ he eventually donated to the

Gallery, the second, ‘The City of Glittering Light’, was

later purchased from him by the Art Committee for £150.

In 1926 he secured for Wolverhampton the bequest of his

late friend, Henry Watson Smith of Stourbridge: a view

of Winchester by Albert Goodwin, ‘French River Scene’ by

Sir Alfred East, and an etching by Frank Brangwyn of

Barnard Castle.[6]

|

| In 1929, he

organised at the Gallery a loan exhibition of Worcester porcelain

from Alderman Bantock. In this way, he anticipated the development

of Wolverhampton Museum Service, a part of which Bantock House would

become years later.

Today, the Bantock porcelain collection has been

preserved at Wolverhampton Art Gallery and displayed at both Bantock

House and the Art Gallery.

In the same year, he gave to the Gallery a

watercolour by Sidney Causer and an etching by William Strang.[7] |

Purchased from M. B. Walker in 1925: Albert Goodwin. The

City of Glittering Light. 1905 |

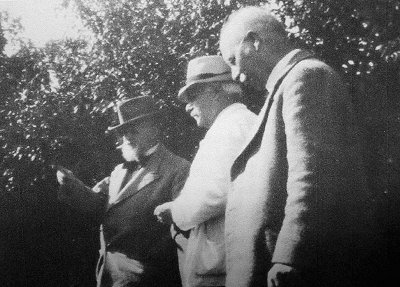

Frank Brangwyn, Frank Short, and M. B. Walker at Brangwyn’s home. C.1933.

Courtesy of Libby Horner. |

This gift was followed by 18 mezzotints and etchings by Frank Short

given to Bushbury Branch Library in the 1930s.[8]

In fact, Walker was a local dealer for Frank Short: the heading of

Walker’s letter paper reads: ‘Fine Art and Literary Valuer. The

Studio, 20 Wolverhampton Street, Dudley.

Engraved works of Sir Frank

Short. RA,

PRE.' [9] |

| But the most important

and long-lasting, the subject of Walker’s joy and pride, were his

relations with Sir Frank Brangwyn.

His first visit to Brangwyn’s

London home, to see his sketches for

Jefferson City Court House, was recorded in 1922.

The result of this visit was close and life-long

friendship between the London artist and Wolverhampton

art connoisseur.

In 1981, Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery purchased

from Wolverhampton art dealer John R. Beards[10]

a correspondence consisting of 250 letters, all but eight of them

from Frank Brangwyn to Matthew Biggar Walker covering a period from

November 1922 to May 1946[11].

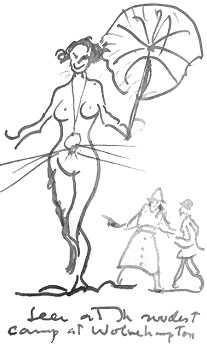

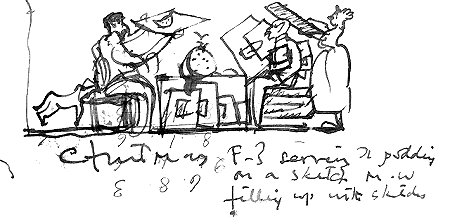

About forty letters contain humorous sketches commenting their

meetings and relations.

One of them, depicting a woman ‘seen at the nudist camp at

Wolverhampton’[12],

suggests that not only Walker went to London and Suffolk to see

Brangwyn, but Brangwyn also visited Wolverhampton. |

Frank Brangwyn’s

sketch in his letter to M. B. Walker: “Seen at the nudist

camp at Wolverhampton”.

©

BM & AG. |

Frank Brangwyn’s sketch in his letter to M. B. Walker:

“Christmas – F[rank] B[rangwyn] serves a pudding on a

sketch. M[att] W[alker] filling up with sketches” © BM &

AG. |

Along with documents

which have been preserved at Wolverhampton Art Gallery and Archives,

they confirm that Walker acted as a mediator between Frank Brangwyn

and the Gallery, establishing and encouraging Brangwyn’s direct

patronage of the Gallery.

In May 1930, ‘Mr. Matthew Biggar Walker

reported that Mr. Frank Brangwyn, RA, the famous artist, had offered

to present to the Art Gallery some of his drawings.’[13]

|

| This present consisted of Brangwyn’s seven original drawings to

illustrate the 1919 edition of ‘Les Villes Tentaculaires’ by Emile

Verhaeren. |

| In April next year,

Walker wrote to the Curator of the Gallery: ‘When I was with Sir

Brangwyn a week ago, he gave me for the Gallery the original drawing

and the etching of ‘St Leonard’s Abbey near Tours’. /…/ I was very

pleased when he so readily made another gift. He said I could give

them to Dudley or Wolverhampton, but I thought our gallery here more

fitting for them.’[14]

Another easy gift was a watercolour by Sir Alfred East ‘The Silver

Seine, France’ the historic value of which is particularly important

today because it bears an inscription: “Alfred East, to my friend

F. Brangwyn, 1.3.1903.”[15] |

Donated by Frank Brangwyn in 1931

“through the

instrumentality of Mr.

Walker”:

F. Brangwyn. St Leonard’s

Abbey near Tours. |

Donated by Frank Brangwyn in 1931 “through the instrumentality of Mr. Walker”:

Sir Alfred East. ‘The Silver Seine, France’. Inscribed:

“Alfred East, to my friend F. Brangwyn, 1.3.1903.”

|

In 1932, Brangwyn

presented to the Gallery a bronze bust of himself by Alfred Drury

(1859-1944). “It was modelled on Mr. Brangwyn’s fifty-first

birthday and presented to Mrs Brangwyn by a great admirer of her

husband’s work and skill. /…/ Since the death of Mrs Brangwyn, Mr. Brangwyn decided that it shall find its permanent resting place in

the Wolverhampton collection.”[16]

In the same year other eight lithographs by Brangwyn were added to

the gallery collection ‘through the instrumentality of Mr. M. B.

Walker’. |

| In 1932, Walker ‘offered a very fine collection of drawings

by Sir Frank Brangwyn for the purpose of exhibition.’[17]

From this modest proposal, a large-scale exhibition emerged, in the

development of which Walker played an instrumental role. It was then

considered one of the most important exhibitions that had ever held

in Wolverhampton.

There were 185 works on show from which only eight

were given by Brangwyn, but 157 items were loaned by M. B. Walker from

his own private collection. He mentioned at the opening that it had

taken him ten years to get the collection together.

The reviewer of

the ‘Express and Star’ noticed that ‘Mr. Walker had persuaded the

artist to lend a number of important paintings that made the

exhibition thoroughly representative.’[18]

|

Purchased in 1933

from the Brangwyn exhibition organised by M. B. Walker.

Frank Brangwyn. The Brass Pot. |

| It was acknowledged that ‘it was one of the most important

exhibitions they had ever held in the town, and had only been

possible through Mr. M. B. Walker, who was a personal friend of Mr. Brangwyn.’[19]

From this exhibition, Brangwyn’s painting ‘The Brass Pot’ was

purchased for the Gallery for £300. Next year, ‘through the

instrumentality of Mr. M. B. Walker’ the Gallery received from

Brangwyn a large Sevres vase which ‘previously had been presented

to him by the French Government in recognition of his services to

art in France.’[20]

In 1934-1935,

Brangwyn donated a number of his works to Dudley, and two

exhibitions of Brangwyn’s works from the Walker collection were

organised at Dudley Art Gallery. Its curator C. V. Mackenzie wrote: ‘The

inhabitants of Dudley have much to be thankful for /…/ the insight

of Mr. Matthew Biggar Walker, their permanent collection of pictures

have been enriched by a fine series of drawings and lithographs by

Brangwyn.’[21]

Promoting

Brangwyn’s works and his own collection, M. B. Walker worked on

national level: after Wolverhampton and Dudley, he organised the Brangwyn exhibition in Liverpool, and Frank Lambert, the Director of

Walker Art Gallery, wrote in April 1935 to M. B. Walker: ‘…This is

probably the only gallery which has the space to show indefinitely

/…/ his own large works and your collection of his work. All the

framed works in your collection were hung immediately we received

them. I was waiting until Brangwyn’s pictures arrived before

including the whole of your collection and his in one large and

handsome Brangwyn Exhibition.’[22]

In 1939, an exhibition was organised at Sunderland Public Art

Gallery, Museum and Library, to which ‘a collection of paintings,

etchings, drawings, etc. by Frank Brangwyn, was lent by M. B. Walker of

Wolverhampton.’[23]

One of the last

Walker’s actions of friendship towards Sir Frank Brangwyn was the

delivery of the artist’s self-portrait to the Uffizi Gallery in

Florence. Commissioned by the Uffizi in 1910, it was for many years

in M. B. Walker’s possession, until in 1949 he brought the portrait to

Florence.[24]

Walker’s influence

was so strong that Brangwyn continued to pay his attention to

Wolverhampton even after M B. Walker’s death in 1950. In 1950 and

1951, Brangwyn again gave to the Gallery twenty five and twenty

three his drawings respectively. Eventually, one of exhibition

galleries at WAG was named ‘Brangwyn Room’. There is another

group of artworks in the Gallery collection which is associated with

Frank Brangwyn: a series of oil paintings and drawings by the

Pre-Raphaelite artist Frederic-James Shields (1833-1911), which is

recorded in the 1974 ‘Catalogue of Oil Paintings in the Permanent

Collection of Wolverhampton Art Gallery’ as given in 1950 by Frank

Brangwyn[25].A close friend of

DG Rossetti and FM Brown, Shields was known as a painter, book

illustrator, sometimes a designer, but his most significant works

were three successive series of mural decorations for the private

chapel of W H Houldworth at Kilmarnock (1876-1880), the Chapel of

Eaton Hall, Cheshire, seat of the Dukes of Westminster (1876-1888),

and for the Chapel of the Ascension, Bayswater Road, London

(1888-1910).

For each chapel Shield provided

designs for stained glass and mosaics: for the Eaton Hall – on the

theme ‘‘Te Deum Laudamus’ and for Kilmarnock –on the theme

'The Triumph of Faith'. For the Chapel of the

Ascension which was commissioned by Mrs Emilia Russell

Gurney, the widow of judge and politician, the Recorder of London

Russell Gurney (1804–1878), he

re-used his earlier designs, but at the same time developed a

complex iconographical programme, uniting Biblical

subjects with allegorical concepts. While the initial idea of

Mrs Russell Gurney was a little decorated hall inspired by Italian

Renaissance architecture and paintings, Shields brought into this

work his intense religious feeling: ‘I feel that if Art may be

used in the service of God at all, if the fine talent may be traded

with in Christ’s mart, then there is a scope and part for it never

yet approached save in a very few exceptional examples. I feel that

if there is to be a spiritual life in this work, and welling from

it, it must be wrought in and by the spirit of life.’[26]

|

|

|

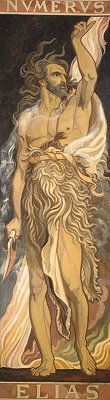

Saved by F. Brangwyn, secured for Wolverhampton by

M. B. Walker:

Frederic Shields. Images of Prophets from the Old Testament.

1880s. |

|

|

|

Images of prophets

and apostles which had been executed at the Eaton Chapel in stained

glass and stone mosaics appeared at the Chapel of the Ascension as

oil paintings on canvas attached to slabs of

slate.[27]

The Chapel was opened in October 1897, just before the death of Mrs

Russell Gurney, but all artistic work was completed only in 1910.

Shields died next year.

In the 1880s, Frank

Brangwyn was directly associated with Frederick Shields through A. H. Mackmurdo and William Morris. He was attentive and analytical

towards the achievements of the elder generation of Victorian

artists and considered Shields one of the best Victorian painters.

He had a very high opinion of the Shields’ work at the Chapel of the

Ascension: ‘The stuff he did for the Chapel of Ascension /…/ is

very fine – irrespective of fashion and the changing of artistic

outlook. These decorations are, in every sense, the most complete

examples of decoration done in England.’[28]

The Chapel of the

Ascension was severely damaged in London Blitz of 1940 and Shields’

mosaics and paintings perished. Brangwyn mourned the destruction of

the Chapel: ‘It is sad beyond words that the beautiful work he

did for the Chapel of the Ascension has been destroyed by bombs… and

so much else! It makes my heart bleed to think of all this.’[29]

According to

Shields’ will, he wanted more than seventy cartoons of designs which

remained in his studio, to be placed in some public institution

which would frame and hang the whole series. The executors of

Shields’ will gave them finally to the Young Men’s Christian

Association (YMCA) for their headquarters in Tottenham Court Road,

London. After destruction of the Chapel of the Ascension, the

cartoons at YMCA became lucky survivors reminding of Shields’

large-scale and harmonious artistic plan.

In 1944, Brangwyn

discovered their location at YMCA. He wrote that his friend William

de Belleroche ‘found them in the cellar. They told him they would

like to get rid of them. I, at once, for the sake of Shields memory

bought them, and have been placing them in such places, as the

British Museum, SK Museum (South Kensington, today Victoria &

Albert. – OB), Fitzwilliam, Walthamstow, Hull, Birmingham,

Ashmolean Oxford etc. etc. so one hopes that some will survive, they

are very fine and highly finished, about 5 feet high many of them.

Rossetti, Madox Brown, Ruskin and others thought highly about him

and his work. One would have thought that the YMCA was the very

place to show such things as they are fine Art, and have in most

cases a spiritual message, but they told my friend that such

subjects had no interest for them and the young. When one is told

this by people who have the control and the opportunity of

teaching in the right directions, one feels it is rather hopeless.

It shows the spirit of our times…’[30]

Besides already mentioned institutions, on Brangwyn’s list were

museums and galleries of Leeds, Cardiff, Liverpool, Manchester,

Nottingham, Dudley, Wolverhampton[31].

It seems that the task was not easy, and there were museums whose

feelings about Shields’ works were similar to those of people of

YMCA. While Fitzwilliam, Walthamstow, Manchester and British Museum

have today in their collections a few Shields’ works donated by

Brangwyn in 1944, the Ashmolean, Victoria & Albert, Liverpool and

Cardiff museums do not. It might be the reason why Wolverhampton Art

Gallery holds not one or two, but impressive number of sixteen

Shields’ cartoons - Matthew Biggar Walker took artworks which were

rejected by other potential recipients.

Wolverhampton Art

Gallery and its Art Committee, however, also seemed to feel

negatively about this acquisition: quite embarrassingly, this gift

was not recorded in the Gallery documentation, acquisition books and

any other existing paperwork. It was also not recorded in the

Minutes of the Art Committee, and it was mentioned neither in local

newspapers, nor in the national professional publications, such as

Museums Journal or The Year’s Art. The date of the

acquisition ‘1950’ given in the 1974 Catalogue contradicts with

Brangwyn’s 1944 correspondence on distribution of Shields’

paintings.

The conclusion is

that Shields cartoons were probably given to the Gallery in 1944

through M. B. Walker, but not acquired. The acquisition record was

developed much later, in the 1970s, when the curators audited the

collection, preparing their catalogue to publication. The date of

acquisition ‘1950’ was based on the recorded Brangwyn’s gift of

twenty-five his drawings. Another possibility is that the cartoons

remained at the Walker’s and were transferred to the Gallery after

his death in 1950.

Wolverhampton and

its Art Gallery benefited for decades from the attention and

generosity of Frank Brangwyn, but it was M. B. Walker who encouraged Brangwyn gifts to Wolverhampton and brought national recognition to

the Gallery. Thanks to him, the Gallery possesses today not only a

representative selection of works by Sir Frank Brangwyn and other

significant British artists of the first part of the 20th

century, but also a magnificent series of the Pre-Raphaelite master

Frederic Shields, a reminder of the artistic and spiritual longings

of the Victorian era and of the tragic artistic losses in time of

war. Regarding the Shields cartoons, Walker probably shared Frank

Brangwyn’s emotions about which he wrote: ‘I am happy in feeling

that we have done the best possible to save the good of a good and

Fine artist.’[32]

|

References

[1] 1901 census.

[2] Express and Star, March 29, 1950.

[3] Ibid; The Year’s Art 1940.

[4] WOL-C-AGPL/1. 20.11.1922.

[5] Express & Star, 22.12.1925.

[6] WOL-C-AGPL/2. 30.05.1926. Henry

Watson-Smith bequeathed to BM & AG a number of Japanese

woodblock prints.

[7] Acquisition book DX894/5/4.

[8] WLO-C-AGPL/3. May 1930.

[9] Watson-Cmith. Donor’s file.

Wolverhampton Art Gallery.

[10] John R. Beards, Tower Antiques, 175 Blackhalve Lane, Wednesfield, Wolverhampton.

[11] BM & AG. F. Brangwyn- M. B. Walker

correspondence. P89’81.

[12] BM & AG. F. Brangwin- M. B. Walker

correspondence. P89’81 – 210.

[13] WLO-C-AGPL/3. May 1930.

[14] WAG. Artist’s file ‘Frank Brangwyn’.

Letter from MBW to A. Cooper, 2.04.1931.

[15] W95. Sir Alfred East. The Silver

Seine. ©Wolverhampton Art Gallery.

[16] Express & Star, 31.05.1932.

[17] WOL-C-AGPL/4. 1932.

[18] Express & Star, March 1933.

[19] Express & Star, March 1933.

[20] Wolverhampton Local Studies. Public

Library and Art Gallery Minutes Book 6. (CMB/WOL/AGPL/5).

[21] Exhibition of Drawings and Paintings

by Frank Brangwyn lent by M. B. Walker, Esq. and David Walker,

Esq.

Dec 1934 -Jan 1935. Dudley Art Gallery.

[22] F. Lambert to M. B. Walker, 24.04.1935.

BM & AG. F. Brangwin - M. B. Walker correspondence.

P89’81 – 244.

[23] The Year’s Art. 1940. P.109.

[24] Brangwyn, Rodney. Brangwyn. London,

1978. P.149-150.

[25]

Griffiths V. and Rodgers D. A Catalogue of Oil Paintings in

the Permanent Collection of Wolverhampton Art

Gallery. 1974.

[26] Ernestine Mills. The Life and Letters

of Frederic Shields. 1833-1911. 1912. P.309.

[27]

www.1911encyclopedia.com

[28] Belleroche, W. Brangwyn’s Pilgrimage.

London, 1948. P.122

[29] Belleroche, W. Brangwyn’s Pilgrimage.

London, 1948. P.128.

[30] F.B. to Eleanor Pugh (niece of A. H. Mackmurdo). 29 May 1944. Walthamstow J697.

[31] F.B. to William de Belleroche. May

1944. Private Collection; F.B. to William de Belleroche.

10.09.1944.

Private Collection; F.B. to William de Belleroche.

Undated. Private Collection.

[32] F.B. to W. de Belleroche. 23 April 1944.

Private collection. Cit. in: Powers Alan. The murals of

Frank

Brangwyn. In: Libby Horner and Gillan Naylor [ed.]

Frank Brangwyn. 2006. P.74. |

|

Return to

the

previous page |

|