|

page 4 Pattingham

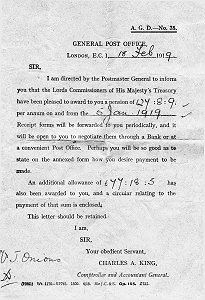

I didn’t know then that the doctor had told my mother that Dad would not work again. He was only 54 years old and he had to retire from the Post Office on a pension of 15/- a week, which wasn’t much since Cathie and Norman were still at school. Father fancied a poultry farm – and he certainly had the room for it. What they did with that cottage just amazed me. A new staircase was put in and it was all painted and papered and it all looked really cosy and they seemed to be happy.

In service again: Stourton Castle Now I felt at last that I could look for what I called a real job. I obtained a post as Second Housemaid with the Grazebrook family, there being altogether fourteen staff at Stourton Castle, near Kinver. I was very happy there. The family consisted of Master, Mistress and a young daughter who had a young lady to stay with her for company, her father being a Colonel in the Indian Army. I was very fond of both girls.

After a while, I got a raise in life! I was made lady’s maid and it was with this post that I was able to go out a lot, having to accompany the young ladies. I was also treated like a lady by the other staff. I was twenty years old and doing very well. I was able to help them at home and Cathie came in for a lot of clothes that I was given from the young ladies, she being just a little younger than they were. We had some lovely holidays in Wales. They had a yacht and we all used to fish for mackerel. Then came the time when my young ladies went down with measles. I had to look after them and I was kept in quarantine, so I did not get home for a long time. I know my birthday came and I got my card from Dad - he never forgot. I still have that birthday card. Back home to Pattingham I arrived home in Pattingham on 22nd January 1922. I’ll never forget it.

I had to ring up my mistress at the Castle and tell her what had happened. She told me not to worry and, two days later, a great big box full of mourning clothes arrived for our use. I just couldn’t stop crying. My father and I had always been so close and I really thought that I would never smile again. Mother did not go to the funeral, nor did we girls; only the men followed the bier that Dad was carried on and he was buried in Pattingham Churchyard, as the snow was gently falling. I was glad that Joe was at home with us to try and sort things out. For one thing, he could at least look after the poultry and the garden when he came home from work. He used to cycle to Wolverhampton to his work at the old A.J.S.. He was also courting a local girl and, at the time of Dad’s death, was contemplating getting married, but didn’t like leaving Mother at this time. You see, when Father died, his pension died with him and Joe’s money was their support, plus what I could give ... so I went back to the Castle. Everyone was so kind but my grief seemed to make me so quiet and I was a changed person. I never wanted to go home because I could not face it without Dad.

Joe got married and Betty got another job in Walsall and lived in digs. I came home to Mother, and I studied what we had to do. It was quite plain that we could not keep the poultry, because their food was costing too much. There was nothing for it but to kill off a few each week. I dressed them and the carrier in the village sold them at Wolverhampton Market for us. I had never killed a fowl. I’d seen Father do it and I just thought "Well, Winnie, there’s always a first time or everything". It was a case of "Needs must if the Devil drives". We picked the flowers in the garden and bunched them up, and the carrier took these, too, and sold them … and that is how we cleared all the stock out. [It is probable that the £77-18-5d was the means that enabled Caroline and Joseph to buy Westfield Cottage, with sufficient ground to keep poultry and to grow vegetables. It appears that they moved to the cottage in about 1920 and set about renovating it. His pension was only 10/6d a week, but a year later, he received a supplementary superannuation allowance, called War Bonus, and an increase under the Pensions Act of 1920, and received a further £14 a year. By January 1922, his total pension was £41-3-1d per annum. This pension ended with his death.] In service: Rudge Hall I heard that they needed a parlour maid at Rudge Hall, so I went after this daily job and got it. I used to ride my bicycle to and from Rudge until the winter came and then the chauffeur used to fetch me and bring me home. Mrs. Fellows, my Mistress, used to send my mother lots of food and I always brought home the milk each evening, since they had their own farm.

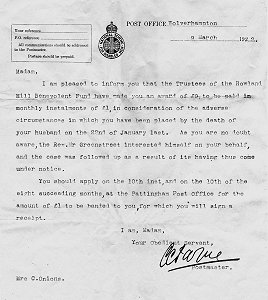

I then had a brainwave! Father had paid one shilling a week into a Children’s Orphan Fund run by Rowland Hill, and Mom confirmed that this was so. I went to Wolverhampton General Post Office where Father had worked and asked to see the Head Postmaster, Mr. Nutt. I told him what I had learned about this fund and he agreed with me that my mother was entitled to a pension for Norman and Cathie. It was only eight shillings a week, but Mother had back pay and she could not believe that she could be so well off!

In service: London Soon after I’d left Rudge Hall, in 1924, I was planting damson trees in the garden, when a big car drew up, and Mother came to tell me a lady and gentleman wanted to see me. The couple had followed Mother into the garden. What a sight I must have looked, dressed in a pair of my brother’s old trousers and wearing wellingtons and digging a hole in the garden. It appeared that a cousin of mine worked for this lady’s mother and had told her that I was "between jobs". She wanted to know if I was willing to take a temporary job for three weeks for Christmas at her house in London. I said that I would let her know and was given her mother’s telephone number to call. It occurred to me that I never seemed to be getting any pleasure out of life and that I was generally getting a raw deal. So I talked it over with my mother who agreed it would be good for me to have a new experience and I had been offered a good wage – and it was only for three weeks. So I accepted. They sent me some money for my fare and I went to London. Mother gave me paper and an envelope and one penny half penny stamp and that was all I had to start my life in the Big City. I arrived in the thickest fog they had had for four years! Mr. & Mrs. Mackle met me, and we had to continue the journey by tram, because they couldn’t see to drive their car. It seemed like an eternity to reach their house. I wrote my letter to let my mother know that I had arrived safely and Mrs. Mackle said that she would post it for me since I would not be able to find the post box in the fog. When I looked at myself in the mirror, my face was black with smog. It was three days before I could see that we had neighbours. It was only a small detached house, very compact and easily run. They were very nice to me and, as I could cook and wait at table, they were very pleased with me. Well, I went for three weeks - and stayed three years!

I had my holidays and they would bring me home to Pattingham if they were coming to her mother’s in Wolverhampton. I remember, too, when I received my first month's money Mrs. Mackle asked me what I was going to do. I said I was going to celebrate as it was the first money I had had in my purse since I arrived there. She was flabbergasted that I would just go walking around the shops for the whole day on my day off. I used to walk all over Hampstead Heath and would come back quite satisfied after my day out – but, by jove, was I hungry! I had learned by now to make all my own clothes and, although I say it, I was always very smart. Mr. and Mrs. Mackle went away a lot and I found that I was left on my own a great deal. It was the time of the Depression and increasingly there was a spate of break-ins in this residential area. I could often hear disturbances in the night, with police whistles blowing, and I was becoming extremely nervous of being on my own. Eventually I found that I couldn’t sleep at all for fear that our house would be next. I mentioned this to Mr. and Mrs. Mackle, so they bought me a dog. He was lovely but he would bark at the slightest sound and it was making me even more nervous. One day my sister Flossie came to see her in-laws in London and visited me. She could see that I was making myself ill. She made up my mind for me, saying that I should leave London and I could stay with her for a while because she was expecting her second baby. Flossie’s new baby was born in November 1927. I stayed in London until after Christmas, and then gave in my notice to leave. Mrs. Mackle didn’t like it but my doctor confirmed to me that it was the right decision. And so I went to stay with Flossie. At Flossie’s in Cheshire … and a meeting Flossie and her husband, Bob, kept a small pub called The Rifleman’s Arms, halfway between Chester and Birkenhead. When I arrived at the station I was surprised to find a taxi waiting for me and thought that things must be looking up with Flossie. However, when I arrived at The Rifleman’s Arms, Flossie knew nothing about a taxi being arranged! It had been sent to meet me … by the man I eventually married! The new baby was very beautiful, but very tiny, and I discovered that she was very ill, yet my sister didn’t seem to realise how ill she was. I told my brother-in-law to get a doctor because I thought she had pneumonia. The doctor came and confirmed my fears. He said the only thing to save her would be to poultice her but she was too weak to stand that. From the chemist we fetched a bottle of four oils, a bottle of Friar’s Balsam, and a steam kettle. I put a fire in the bedroom and got the steam going and rubbed her with four oils. I sat with her for a week, just wetting her lips with brandy and water. How I prayed for that little girl. One day she seemed a little better, and I said "smile for Auntie" … and she did! If I had won the pools I could not have been more excited. She recovered fully, and grew up to be a lovely girl, who won many prizes for show jumping. I then married and had three children … but that is another story, and perhaps one day, I’ll write about that. Winifred's manuscript ends here. Go on to the next page to read a short account of the later lives of Winifred and the rest of the family. |