|

Out of a job in 1858 Wallis took a temporary post at the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum). He organised an exhibition intended to display the work of Schools of Design and it consisted of objects which had been manufactured from designs by students of Schools of Design. This would have promoted the usefulness of such schools and acted as a practical demonstration of their value. In 1858, HMSO published a Catalogue of the Exhibition of Works of Art by the Students of the Schools of Art; it had an introduction by Wallis.

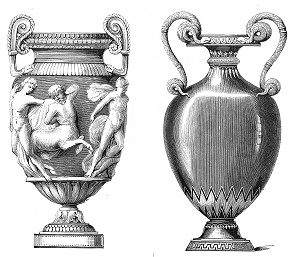

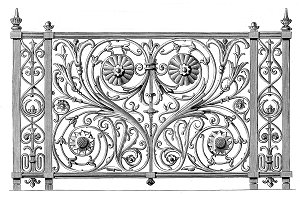

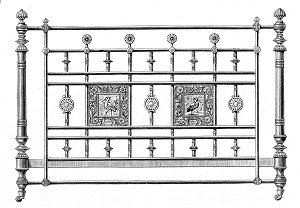

Thus the Catalogue of the Wolverhampton and Staffordshire Fine Arts and Industrial Exhibition of 1884 has a whole section entitled “Collection of Objects lent by the South Kensington Museum”. This consisted of a number of cases and frames containing metalwork, glass, jewellery, carvings in wood and ivory, textiles, potteries and electrotype reproductions of plate, as well as photographs, including coloured photographs, of similar items and of furniture, enamels, wall paintings and other works of art. These cases and frames may have been got up for this exhibition or they may have been the standard fare, originated by Wallis, which was made available on demand.

Another interesting example of this kind of work was a loan collection of furniture sent to the Bethnal Green Museum in 1871. This contained a number of Japanese examples, which Halen thinks may have influenced Dresser towards his long and deep interest in Japanese design.

It seems that in his work Wallis did not forget his home town. Whilst at the South Kensington Museum he accepted gifts to the Museum of items of Bilston enamels. The first gifts were not of works of the highest quality and, at the time, it was accepted that any inferior and cheap enamel work could be attributed to Bilston and anything better to Battersea. Eric Benton has suggested that Wallis accepted these inferior works as “He was a Wolverhampton man and may have wished to have examples of the work of a local industry”. Better examples were then given and in 1874 he held, at the Museum, a Special Exhibition of Enamels. He noted that some of these were of a far better quality than Bilston was supposed to have produced and “but for the fact of their authenticity as products of this ‘black country’ village being indisputable, they would be accredited to Battersea”. Wallis can, therefore, be credited with being the first person to clearly separate Bilston enamels from Battersea enamels and to have put the Bilston products in their rightful place.

In 1860 Wallis again interested himself in Wolverhampton causes. Art Schools were a favourite cause of his and he had helped promote the Wolverhampton Art School. By 1860 this school was in trouble. Patrick Quirke finds a number of causes of its problems, one of which is that the founders, under Wallis’ influence, may have been too grandiose in their plans for the school. In 1859 Charles Mander (with Henry Loveridge, its chief financial backer) decided that the way to get the school and himself out of a financial hole was to get the town council to adopt the then new Public Libraries Act and take over the art school under that guise. The council called a public meeting to decide whether or not to adopt the Act. At this meeting, says Patrick Quirke, “the vocal opposition to Mander's scheme caused this meeting to be described as one of the most boisterous ever to be held in Wolverhampton’ [Wolverhampton Chronicle 27th June 1859]. Despite Mander's marshalling of his supporters, "the greatest disorder prevailed" when a resolution was put to the meeting that "a Free Library in connection with the School of Art would add greatly to the prosperity of the town" [ibid]. This was greeted by cries of "We don't want it! We won't have it!" [J.Jones op cit p82]. A more direct proposal:- "Would they have a Free Library or would they not?" was answered with shouts of "No! No!" [ibid].

In 1860 a further attempt was made. On 13th April 1860 Wallis travelled up from London for the meeting but, he reported, “no opportunity could be given for the discussion of the question.” Clearly the greatest disorder prevailed again. This caused Wallis to write a very long letter (perhaps at the instigation of Mander and Loveridge) to the Wolverhampton Chronicle, which was duly published by them and then reprinted as a broadsheet, (copy now in Wolverhampton Archives). His argument is that free and international trade, and thus greater competition, had arrived; that one essential way to meet this commercial threat was to improve design; and that to improve design you needed art schools. Wallis discusses this specifically in the context of local trades: japanning, iron casting, brass casting, locks, steel wares. He again exhibits a considerable knowledge of these trades and of their economic situation as well as their design and production situation. And, as usual, he does not mince his words. But it was to no avail. The school had to struggle on, on its own, for more than a decade before it finally became a public institution. |

||||||||||