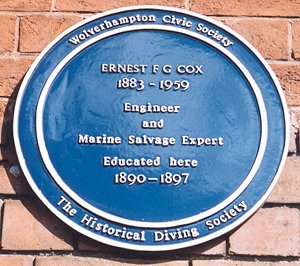

Ernest Frank Guelph Cox was born on the 12th March 1883 at 55 Pool Street, the eleventh and last of the children of Thomas and Eliza Cox. Thomas had a tailoring business. Ernest attended the Dudley Road School (now the Blakenhall Community Centre) until the age of 14. His father found him a job as an errand boy to a local draper. It is said that while running errands round town he one day got into the Commercial Road power station and was fascinated by it. He immediately read everything about electricity and power generation that he could lay his hands on and, after a year, and at the age of 17, went to the power station and persuaded them to give him a job. After a year he applied for the post of Assistant Chief Engineer at Leamington. He lied about his age and his experience. The appointments board found this out but Cox still managed to persuade them to appoint him. Two years later he got the job of Chief Engineer at Ryde, IoW, which involved designing and building the power station from scratch. He made a great success of this - at the age of 20. He then moved to Hamilton to perform a similar task and then on to Wishaw to design and build yet another power station. Whilst at Wishaw a local councillor, Robert Miller, got to know him and asked him to take a post running his large steel works, Overton Forge. He thus left the electricity industry, where he had established a national reputation, and went in to iron and steel. He married the boss's daughter. Cox wanted to start his own forge as he expected that supplying material in the war he saw coming would be highly profitable. To finance this operation he approached his wife's cousin, Tommy Danks, a rich playboy, to put up the capital. This Danks did on condition that he did not have to take any part in the operation. It was natural for Cox to return to the Black Country for this enterprise and the firm of Cox & Danks was set up in Oldbury in 1913. Cox's prediction about the war was right and the firm made vast profits making munitions. In 1918 Cox bought out Danks - but the company name was maintained. Cox then set about recovering scrap metal from the battlefields of northern Europe and had to set up a second foundry, this time in Sheffield, to cope with all the material. He also ventured into ship breaking, buying two decommissioned battleships and setting up a yard at Queensborough to deal with them. But as the battlefields were cleared scrap metal became scarcer and, in any event, with the end of the war, the demand for iron and steel was rapidly falling. Cox was at something of a loose end but a proposal to sell off the remains of the scuttled German fleet at Scapa Flow provided him with an opportunity and a challenge. Ernest Cox was responsible for finding many of the ships from the German High Seas Fleet that were scuttled in Scapa Flow on 17th June 1919. Out of the 74 ships that were interned at Scapa Flow, 51 were sunk and 43 of them subsequently raised. Only 8 still remain. The total weight of the ships that were sunk was over 400,000 tons. The largest salvage operation in history was soon underway and the Scapa Flow Salvage and Shipbreaking Company was formed in 1923, to raise some of the torpedo boats. Over the next 8 years he undertook a massive operation to raise the ships. It was to become one of the greatest feats of marine salvage ever accomplished. He purchased and modified an old German floating dry dock and lifted 26 torpedo boats, and broke them up for scrap in between August 1924 and April 1926.

Finally more compressed air was pumped in to bring the upturned hull to the surface. The work to raise the ship was undertaken by thirty men and took nine months to complete. In between 1927 and 1931 another two battleships were lifted, together with two battlecruisers and a cruiser. Some idea of the difficulties that were encountered can be gained from a brief description of the raising of the cruiser the Bremse, which was brought to the surface in 1929. On her scuttling she was almost beached by the Royal Navy off Toy Ness, but she finally foundered and turned on to her starboard side as she sank. The wreck lay on a slope with her bow and part of her port side exposed at low tide. Immense difficulties were caused by escaping fuel oil from the ship's double bottom tanks, which had to be turned completely upside down before lifting could begin. To achieve this most of the superstructure had to be removed. The leaking hull was taken to Lyness for breaking as it wasn't feasible to tow it further. The final ship raised by the company was the battleship Prinzregent Luitpold in 1931, after which the work was taken over by Metal Industries of Charlestown. Metal Industries employed many of the Cox and Danks' workforce, who by now were extremely experienced in this field. Salvage work continued until the outbreak of war in 1939. The following ships were raised by Cox and Danks

Cox had set about this task with no experience of marine salvage. But to carry out the task he was responsible for many new developments in the science. In fact he lost about £10,000 on the whole Scapa Flow operation but he made himself a great reputation. He was awarded a CBE and appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath. The financial loss did not matter much as the rest of his business was very successful financially and Cox was a very rich man. Cox's last marine salvage work was in 1941. The rest of his business continued to flourish. He died, in Torquay, in 1959. I would like to thank Ian Jukes for locating this information on Cox's marine salvage work. Information on Cox's early life has been taken from Tiny Booth's book, "Cox's Navy", Pen & Sword Books Ltd., 2005. That book contains an extensive bibliography or works about Cox. |