|

Bayliss, Jones & Bayliss

William Bayliss,

the founder of the firm, was born in 1803 into a

Shropshire family who moved to Priestfield, where he was

born. His father Moses came from Benthall Edge, his

mother came from Horsehay. He worked for Samuel Ferriday

who owned coal mines and an ironworks at Priestfield.

Moses was a blacksmith who had his own blacksmith's shop

and looked after the mine pumping engines. Much of his

work was for the miners, sharpening their picks, shoeing

their horses and repairing hand tools.

William was the

third of eleven children. He disliked school and left as

soon as possible. Before his tenth birthday he was

working seven days a week in one of Samuel Ferriday's

mine pumping engines. Although an easy job, he was left

much to his own devices, and rarely saw anyone else. He

particularly disliked working at night when he had to

walk in the dark, to or from the engine.

|

|

|

A simplified family tree.

When William was

around eleven years of age his father moved his business

to Monmore Green to look after Mr. Ferriday's engines

there, and William worked on one of the pumping engines

on the site. When he was about fifteen years old he

began working on a winding engine, which meant that he

didn't have to work on Sundays. His father wanted him to

improve himself and so found him a job as a blacksmith.

Work was much harder in the blacksmith's shop, but it

was not so lonely, and much more enjoyable. Around this

time he became a devout Christian which would soon

dominate his life.

William gradually took over his father's business. He

was an efficient lad and when he started keeping records

and introduced "pay on the nail", it excused his dad the

Saturday journey around the public houses trying to get

his mining customers to pay their bills.

|

|

This photo, which was taken at

the churchyard at Empingham, Rutland, was kindly sent by

Alan Murray-Rust. It

carries the following lettering:

Bayliss & Co. Wolverhampton.

Could this be an early example

of William Bayliss's work?

If anyone can confirm this,

please

send me an

email.

|

|

In 1825, at the age of

twenty one, William married one of his Sunday school

teachers. She was a regular member of

the Wesleyan Chapel in John Street, Ettingshall, where he was class leader of the weekly

prayer meetings. They moved into a house in George

Street, Ettingshall and over a period of around twenty

five years had 14 children, but ten of them died young.

The survivors were two daughters, and two sons, William and Samuel,

who later joined the firm.

A few months later his

father suddenly died. William took over the business,

but as well as his work in the blacksmith's shop, he had

to carry out repairs on the mine pumping engines. It was

extremely dangerous work. Many people were killed or

injured in mine shafts as a result of brick or rock

falls. They were dry-bricked, or un-bricked where there

was rock or coal. The shafts were deep with three

rod-operated pumps. The lowest pumped water into a

cistern, the second pumped water from the cistern into a

second cistern, and the third pumped the water to the

surface.

|

|

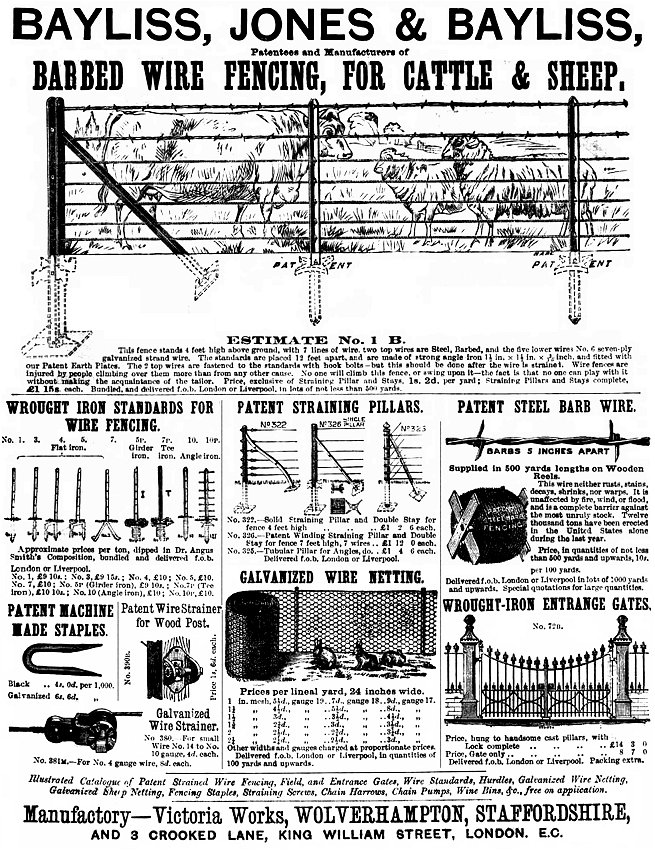

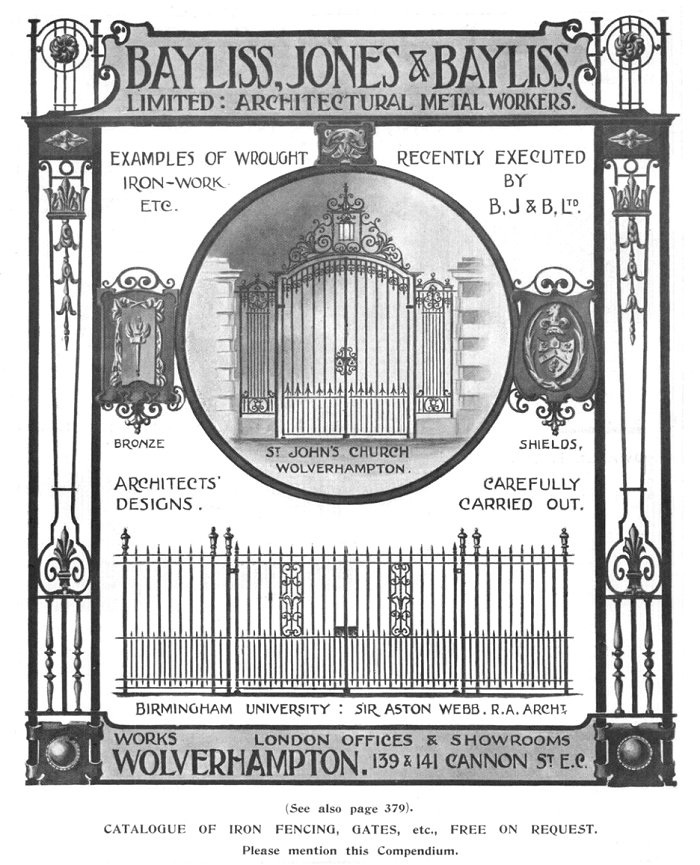

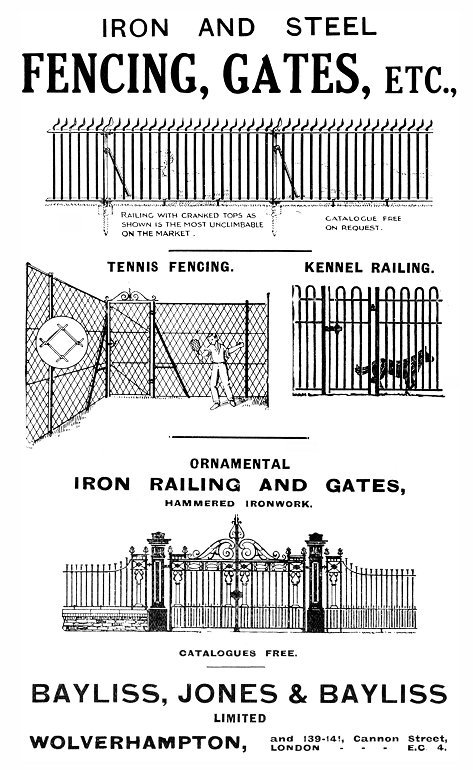

An advert from the British Trade Journal,

1st June, 1882.

An advert from 1885.

An advert from 1885.

An advert from 1885.

An advert from 1885.

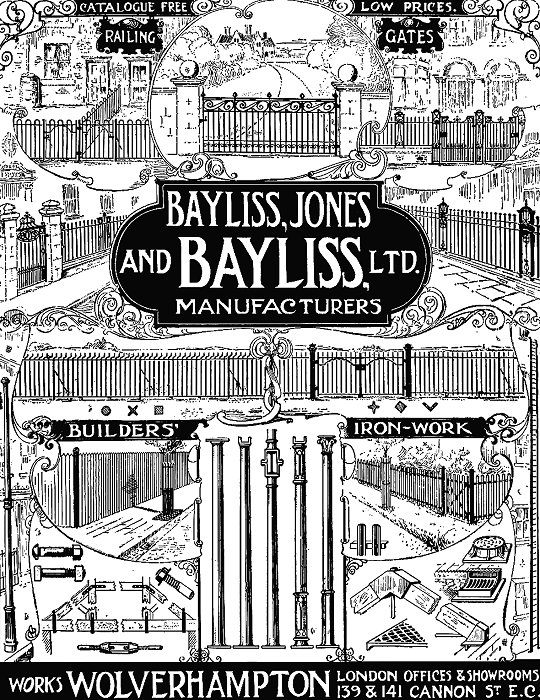

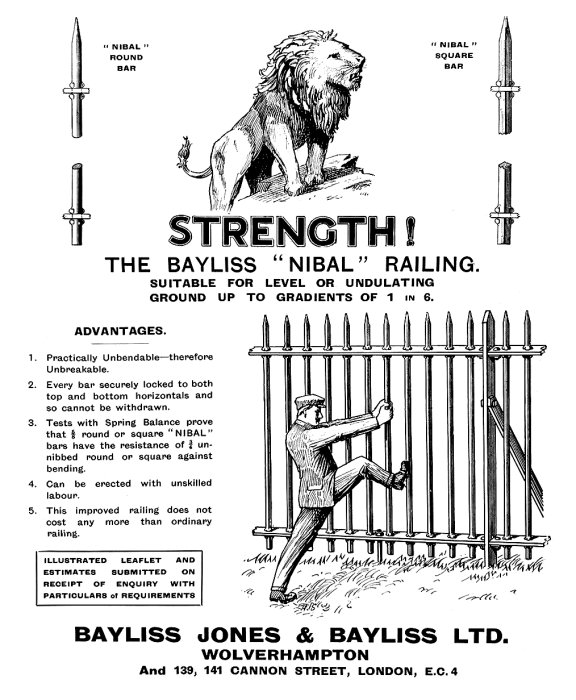

An advert from 1912.

An advert from 1913.

|

An advert from 1914. |

William saved

hard and bought a large plot of wasteland in Cable

Street, Wolverhampton where he established the Victoria

Works in 1826. He began to produce iron products

including sheep hurdles, railings, gates, stable

fittings, ornamental ironwork and chains for mining and

shipping.

Sadly William's first wife died young. She discovered

a lump in one her breasts, and had a mastectomy.

Although successful, other cancerous growths appeared in

her lungs. A little while after her death he married

again. His second wife had previously married and had a

daughter from her first marriage. William entered into a

business partnership, but was having health problems

caused by the smoke and sulphurous fumes that were often

in the air at Ettingshall. Because of his chest

complaint he was unable to cope at work, and felt that

his partners were taking advantage of him. After a

disagreement in 1853 the partnership was dissolved. |

|

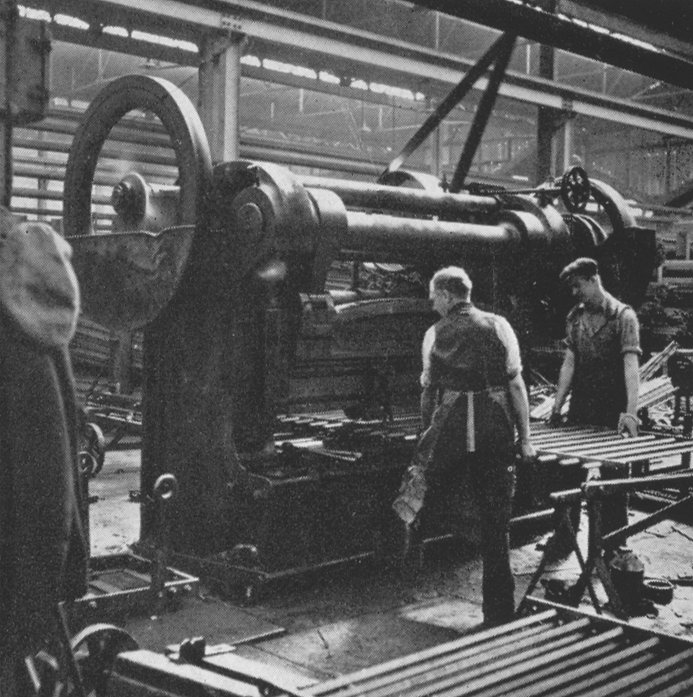

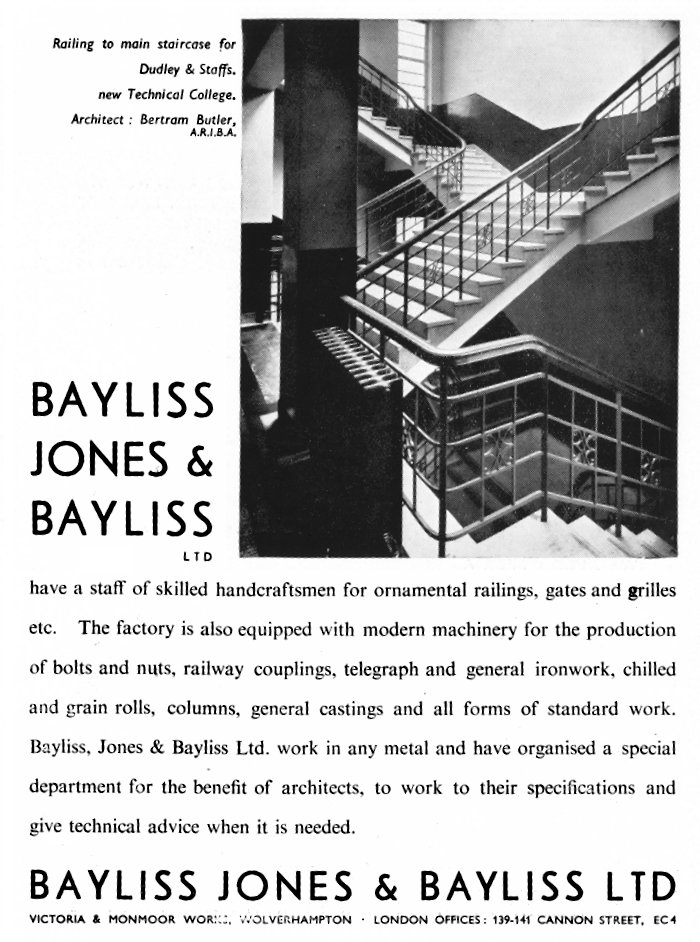

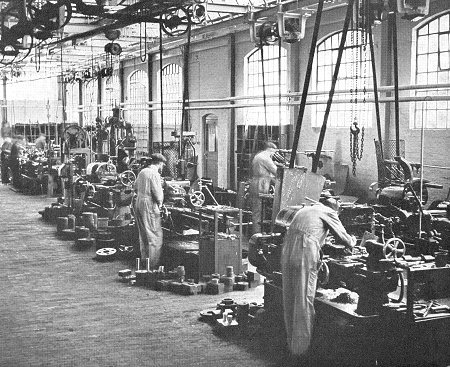

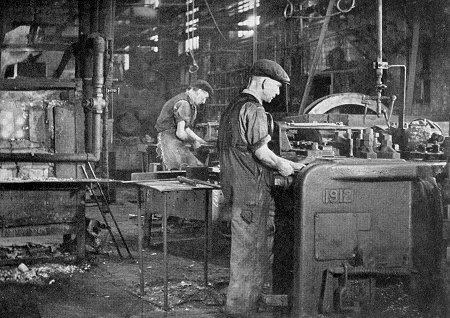

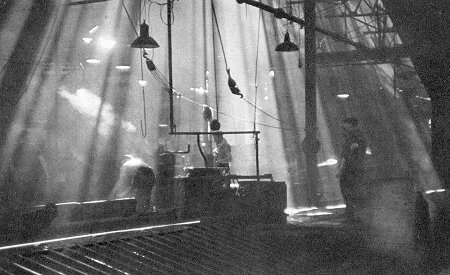

Making railings in the machine

shop. |

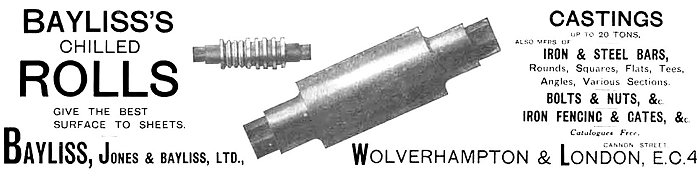

An advert from 1924.

|

An advert from 1929. |

|

An advert from the 1930s. |

|

Eventually his

brother Moses, who had been a nut and bolt maker at

Providence Works, Darlaston, joined him in the venture.

The two firms were amalgamated as W. & M. Bayliss of

Victoria Works, Monmoor Green and Providence Works,

Darlaston, with a London office at 43 Fish Street Hill,

Eastcheap. In 1859 they were joined by Edwin Jones, an

iron trader from South Wales who had previously married

William's daughter, Jane. The partnership then became

Bayliss, Jones and Bayliss.

|

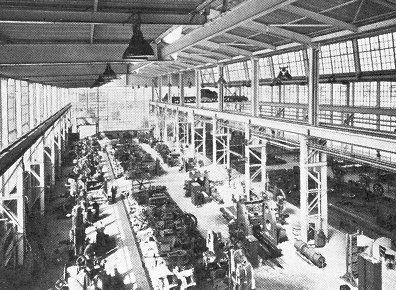

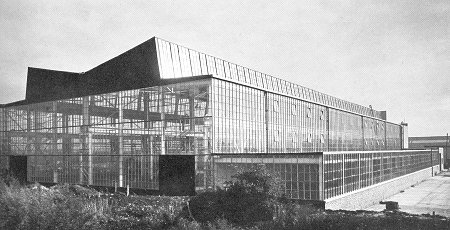

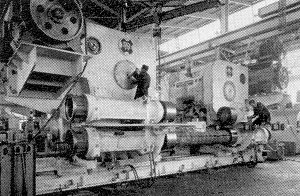

The new machine shop in 1949. |

|

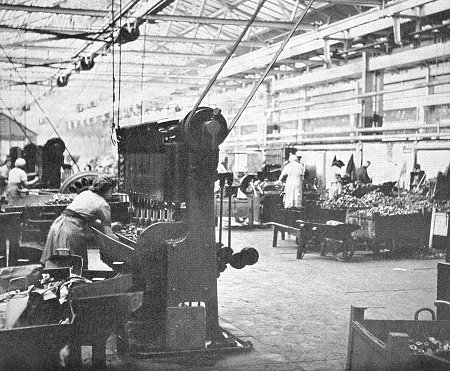

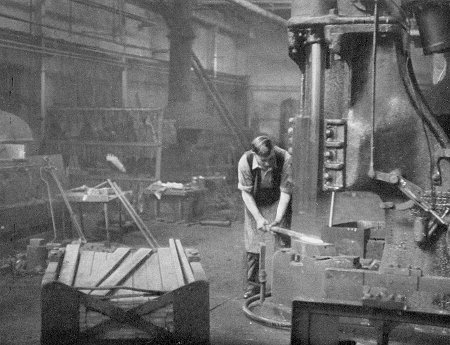

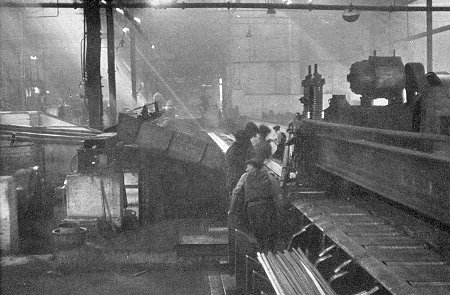

Traditional methods still in use

in 1953. |

The company were very successful

and Mr Jones became resident in London, running an

office at 84 Cannon Street E.C.

It seems that Moses went to America

to introduce the rolling of corrugated sheet iron, but

this can't be verified. However, Moses was the father of

Wolverhampton born Sir William Maddock Bayliss, who

later became a distinguished physiologist. In 1902, at

University College London, with E.H. Starling, he

discovered the hormone secretin and established the role

of hormones. Secretin is used today as an intervention

for autism.

Sir William was also a

non-executive director of Bayliss, Jones & Bayliss.

In 1873 a Wolverhampton Trade

Directory lists William, the founding member of the

firm, as living in Oaks Crescent. |

|

William moved

there to get away from the smoke and fumes in Monmore Green.

He had been

advised to “move to the fresher atmosphere of

Wolverhampton”. Oaks Crescent was on the edge of a rural

district. His journal expresses his pleasure at the

blossoming trees, the clean air and the singing of the

birds in the garden of his new home. A few years later,

his doctors advised him to retire to the south. The

family initially moved to Clifton, but because of the

smoke and fog there they moved again to Torquay, where

William lived until his death in 1878.

|

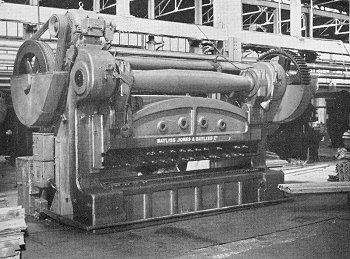

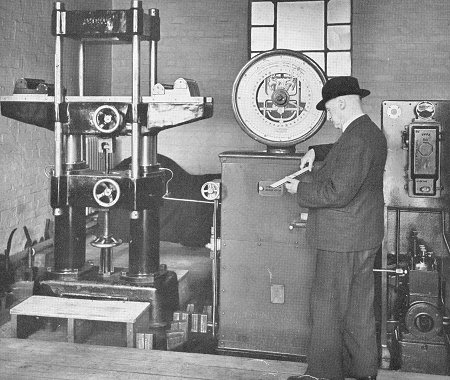

One of the company's large

machines. |

| |

|

| View the fine example

of Bayliss, Jones & Bayliss fencing and gates that

are in Grangewood Park, South Norwood, London. |

|

| |

|

| The following article appeared in 'The Engineer' on

1st October, 1880: |

|

Bayliss, Jones and Bayliss –

Rivetless Hurdles

Messrs. Bayliss, Jones and

Bayliss of Wolverhampton, and King William

Street, EC, have recently brought out an

improvement in iron hurdles, gates, etc. which

consists of securely fastening the ends of the

horizontal bars to the uprights without

riveting. |

|

|

It is shown by the annexed

engravings.

A

shows the horizontal bar threaded through the

upright, ready for clenching; and drawing

B the horizontal bar

after it has been clenched to the upright, from

which it is impossible to move without cutting

the horizontal and upright to pieces.

Hurdles made upon this

principle are found to be very strong and rigid. |

| The mode of manufacture moreover, demands

the employment of first-class iron, as none

other will stand the test of clenching the ends

at the short bend. The hurdles will consequently

bear the rough usage to which they are very

often necessarily exposed. |

|

|

An advert from 1953. |

An advert from 1935. |

| An article from The

Engineer. 30th October, 1885.

The Eureka Lock Nut

The lock nut

illustrated in the accompanying engravings

is now being brought out by the patentees

and manufacturers, Messrs. Bayliss, Jones,

and Bayliss, of Wolverhampton and Cannon

Street. A simple and effective locking

arrangement for such work as fishing rails

is a great desideratum.

|

Many forms

have been brought out, but none

so simple as the Eureka, which

is made in the ordinary way,

with the exception that on the

outside surface of it, a small

pyramidical prominence is left,

as seen in Fig. 1. After

screwing the nut, this

prominence is compressed and the

outside surface made level, but

in the act of compressing it,

three threads of the nut are

deformed where the prominence

has been pressed into the nut,

as shown in Fig. 2. |

|

|

The nut will run easily on

the male screw or bolt until the

deformed or irregular threads

are reached in the nut, when the

spanner is necessary, and with

its aid the nut, while passing

along the bolt, deforms the

thread, as seen in Fig. 3. so

that at the point where the

operation of screwing

terminates, the threads of the

bolt accommodate their shape to

the deviation in the three

threads of the nut in such a way

that it is impossible for the

bolt or nut to be moved either

way without the aid of a spanner

and considerable force. |

| The makers have had these

nuts on a large and powerful

multiple press for nine months

without requiring to be touched,

whereas previously they had used

other lock nuts, which, owing to

the continual vibration of the

machine, needed constant

supervision and daily

tightening. |

|

They claim several

advantages as possessed by this nut,

including simplicity, security, cheapness,

that it will not move even if the bolt

becomes elongated in work, and that it can

be used several times. They make them in

iron and in steel, but they specially

commend mild steel bolts and nuts. |

|

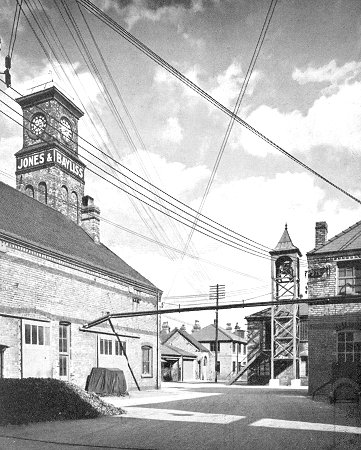

Victoria Works yard and the old clock tower.

An advert from 1901.

|

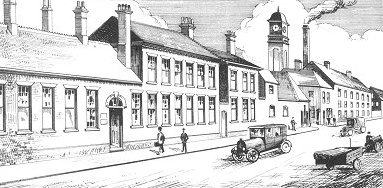

Cable Street. From the 1928

catalogue. |

By this time the company produced large numbers of

rails, fish plates,

chair spikes, fastenings and nuts, for the railways, and

nuts & bolts, and all kinds of iron work, from massive

cables and anchors to half-inch chains and small screws. |

| His son William, a quiet and

retiring sort of man, who was at home in the office,

lived at The Firs, Merridale Road.

Samuel, his brother, was more

active and worked in the pattern shop of the foundry.

William would later become chairman and be succeeded by

Samuel in 1925. |

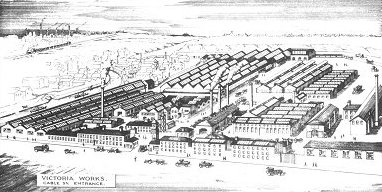

Victoria Works. From the 1928

catalogue. |

|

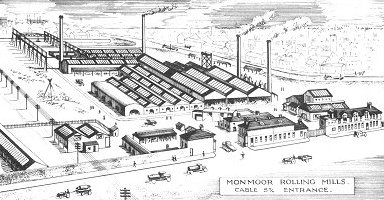

Monmoor Rolling Mills. From the

1928 catalogue. |

In 1896 the company purchased the

Monmoor Ironworks on the other side of Cable Street,

which included rolling mills and puddling furnaces. The

iron works were founded by Mr. E.T. Wright and Mr. David

North to produce high quality iron plates and sheets

using the 'Monmoor Works' brand name. From the late

1850s they were managed by George Adams, who founded the

Mars Iron Works. |

An advert from the GWR Magazine, July 1932.

|

The company produced a wide range

of products for use in the garden, in sports grounds, and on

the farm, as can be seen from the advert opposite.

Courtesy of Brian Shaw. |

| A bench-end that was cast in the

company's foundry. Courtesy

of Brian Shaw. |

|

A close-up view of the maker's name on the

bench-end. Courtesy of Brian Shaw.

| By the early 1870s Mr. David

North retired after accumulating a large fortune, and

E. T. Wright continued to run the business alone.

It is believed that George Adams

still continued to manage the works as well as running

his own nearby iron works.

In 1901 the company was floated on

the Stock Exchange, but in the early 1920s sales fell

and problems followed. Sales to the railway companies

were the worst affected, although the fencing side of

the business suffered as well.

|

A typical large fabrication made

at the works. |

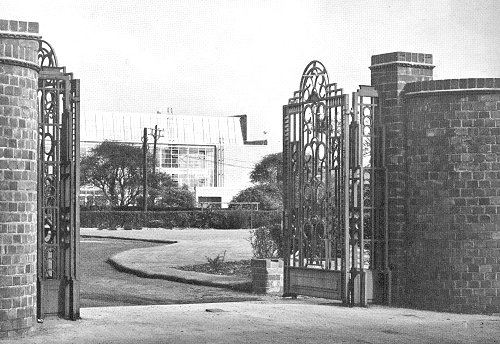

| Gates made at the

works for the Territorial Association

Headquarters in Wolverhampton. |

|

The G.K.N. company history

reports the rumour that "William Bayliss, the then

chairman and son of the founder, had diverted capital

from the business into a country estate and had

speculated unsuccessfully on the Birmingham Stock

Exchange, drawing the company in to debt". |

|

Around 1922

Thomas Swift Peacock, representing the G.K.N. Group of

Companies, negotiated the purchase of Bayliss, Jones and

Bayliss. Peacock was in charge of the group’s Atlas

Works in Darlaston. The G.K.N. Board had given him full

control of the nut and bolt and railway fastening

departments of the Midlands.

Though a subsidiary of G.K.N. from

1922, the company kept its own name and the Bayliss

family continued to provide its management. It is

generally understood that Mr. Jones, who was still in

control of the London offices, forced the issue by

declaring his willingness to sell his portion of shares

to G.K.N. Mr Jones' son Edwin, his son-in-law, Sir

Murray Hyslop and finally his grandson Roy Hyslop,

followed him in managing the London office and

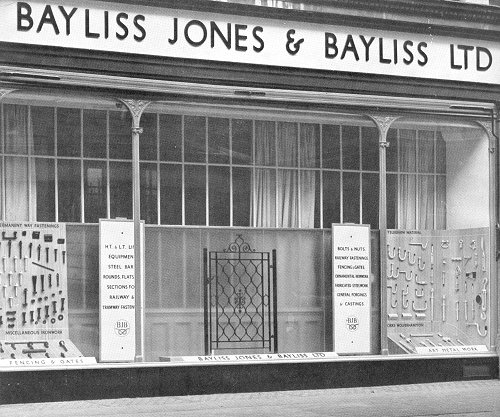

showrooms, which had expanded to 139-141 Cannon Street

by 1938. |

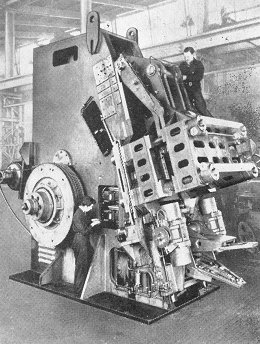

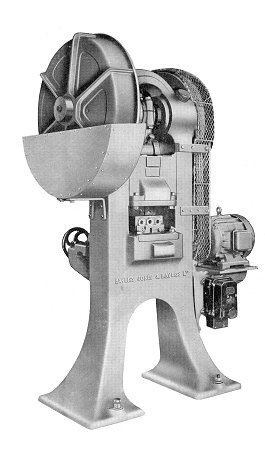

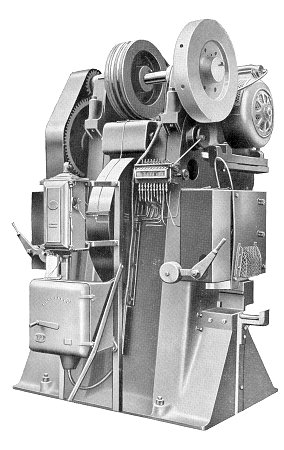

A special purpose BJB swaging

machine. |

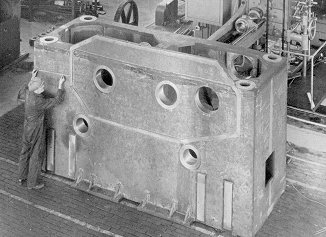

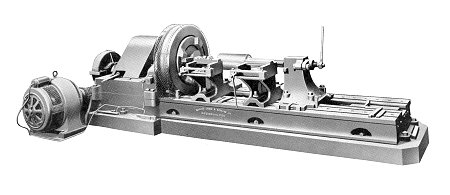

A 13ft. by 10ft. 6ins. press head

constructed at the works in the late 1950s. |

Under Thomas

Peacock, in 1927 and 1928, a new screw rolling shop

opened, the bolt works were reorganised to make

production more efficient and a new mill for the

conversion of billet into bar, opened at Monmoor Works.

The company

seems to have concentrated more on the fencing, railing

and general ornamental ironwork side. In the great

slump of 1929-30 they were hit hard but recovered

strongly from the mid 1930s, which were the company’s

most successful years.

Samuel Bayliss

died in 1932. His sons, P.S. and F.W. Bayliss, joined

the board in 1921 and 1925 respectively, and they became

the joint managing directors in 1928. |

|

The company

continued to produce high quality ornamental ironwork

such as gates, fences, balustrading, railings, and tree

guards, and became well known for its products.

A large

proportion of the work at this time was for county

councils, carrying out their 'improvements' of

substituting railings for hedges. Demand for

balustrading to span the many new bridges extending over

Britain's motorways also kept the firm busy.

|

The Forging Shop built in the late

1950s. |

|

An advert from 1948. |

|

An advert from 1927. |

The products

which the 1953 Wolverhampton Official Handbook mentions

include: plain and ornamental wrought iron

fencing; for railways - black bolts and nuts, screw

spikes, chair bolts, fishbolts and other fastenings;

equipment for overhead telegraph and telephone lines;

fabricated steelwork; general forgings;

agricultural equipment - tractor toolbars, heavy tractor

cultivators, plough beams and brackets, hay rake frames,

etc.; and a recently created department for the welded

steel fabrication of machinery frames, bed-plates, mill

plant, constructional steelwork, agricultural

implements, containers, stillages, hoppers and guards.

The company's

steel rolling mills, with a capacity of 1,000 tons per

week, were kept busy, as orders for miles of railings at

a time were not uncommon. The amount of metal being used

in the works must have been enormous. The modern

galvanising shop had a capacity of 350 tons per week and

was not only used for the company's own products, but

also did outside work. |

The London office and showroom at 139 Cannon

Street.

| By the mid 1950s the company employed around 1,500

people, many of whom had completed 30, 40, 50, or even

60 years service at the works. There were tennis courts,

a bowling green, a netball court, a sports ground,

football and hockey pitches, a cricket ground, and a

children's playground, complete with swings,

roundabouts, and a paddling pool. The Managing

Director at the time was Mr. Roy M. Hyslop, the great

grandson of Mr. Jones, one of the company's founders. |

A company dinner

at the Victoria Hotel, in November 1952.

Courtesy of Nina McCarthy. |

|

| Employees were out

in force at the Civic Hall, to celebrate a

colleague's wedding. 27th March, 1952.

Courtesy of Nina McCarthy. |

|

At this time the

company had a wide variety of customers, including local

authorities, architects, power stations, the Admiralty,

the war Office, the Ministry of Works, the Air Ministry,

and private companies.

The company

produced rail fastenings for British Rail and designed

various types of fasteners, mostly resilient fastenings

for long welded rails. In addition to their standard

lines of railings and gates, they also made one-off

pieces to the designs of the individual customer, or

very often, his or her architect.

|

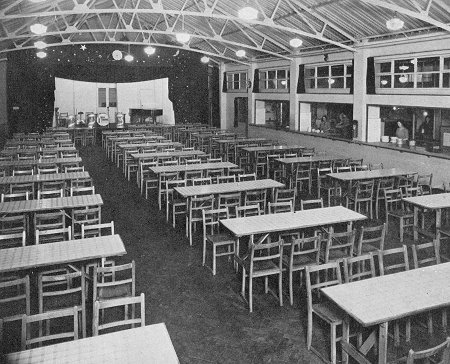

| The canteen could provide hot meals for up to 400

people.

It had a polished wood block floor to enable the

dining area to be quickly converted into a dance floor

for evening events. |

The canteen. |

|

The dining room. |

The dining room had a fully equipped stage so

that all kinds of events could be held there. The

serving hatches can be seen along the right-hand wall.

|

| A corner of the large kitchen. |

|

|

Part of the Test House for

tensile, Brinell, and Izod tests. |

| Part of the tool room that

supplied precision tools and forging dies. |

|

|

A corner of the Screw Shop

where nuts and bolts were finished after forging. |

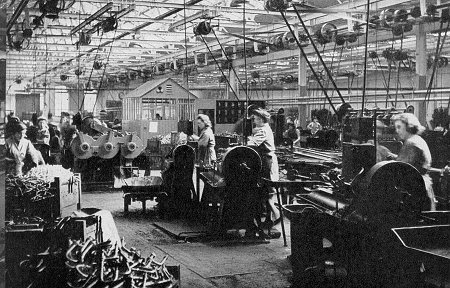

| Part of the Bolt and Screw

Spike Forging Shop. |

|

|

The Inspection,

Packing and Despatching Warehouse from where goods were

sent by road, rail and canal. |

| Another view of

the Inspection, Packing and Despatching Warehouse. |

|

|

The Production

Machine Shop for the company's electrical overhead

transmission line equipment. |

| A horizontal

forging machine producing parts for the electrical

overhead transmission line equipment. |

|

|

Working on one of the Massey

Hammers in the Smithy. |

| Another of the Massey Hammers

in the Smithy. |

|

|

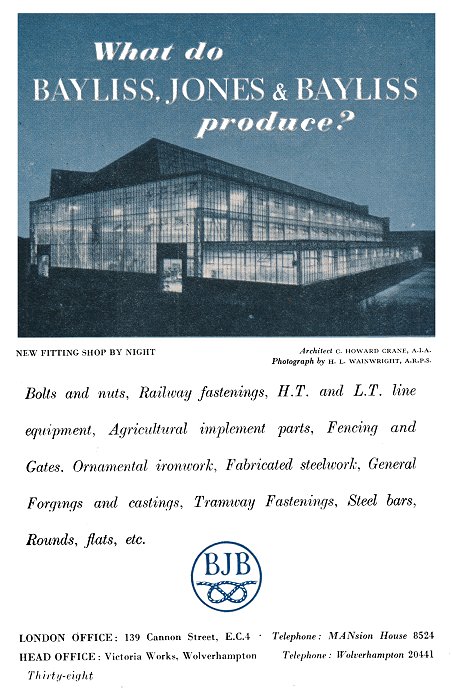

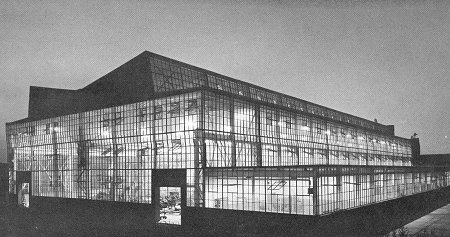

The new Machine Shop. |

| The new Machine Shop at night. |

|

|

Number 3 Rolling Mill. |

| The gravity, semi-mechanical

cooling bed for the rolling mill. |

|

|

The cutting machine that could

cut twelve ⅞ inch diameter

bars in one operation. |

A presentation in the works. Courtesy of Nina

McCarthy.

The foreman's dinner at the

Victoria Hotel, May 1951. Courtesy

of Nina McCarthy. |

Long service awards, July 1953. Courtesy

of Nina McCarthy.

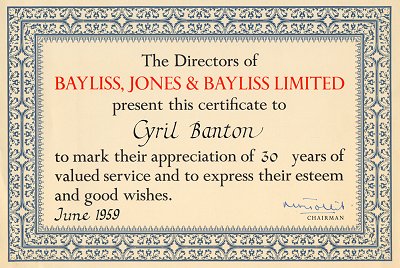

Cyril Banton's long service

award. Courtesy of his daughter, Nina McCarthy. |

| |

|

| View some of the

forgings made by the company |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| View some of the

electrical overhead transmission line equipment

made by the company |

|

| |

|

|

From 1968

exciting times lay ahead when the factory was

reorganised, and much of the plant and buildings

were brought up-to-date. Large sums of money were

invested in the site, which became known as GKN

Machinery Limited. The new company was formed

following the merger of several GKN companies,

including Bayliss, Jones & Bayliss Limited,

and Peco Machinery Limited,

The 1,450

skilled workforce became engaged in the design,

development and manufacture of a wide range of new

engineering products. Many of the company's

traditional products were still produced, such as

fencing and heavy machinery, and the new company was

divided into four divisions. |

An advert from 1971. |

|

The Metal Forming Plant building

on the Monmoor Works site. Courtesy of Nina McCarthy. |

|

The Metal Forming Plant

Division (MFP) manufactured rolling mills and

ancillary equipment under licence from Moeller &

Neumann, G.M.B.H. West Germany.

Products included steelworks

plant, billet inspection machinery, special purpose

machine tools, steel fabrications up to 100 tons,

and general engineering projects. |

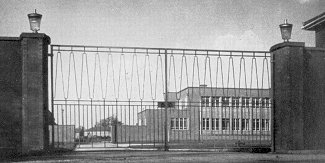

The entrance to the canteen and grounds

with the new machine shop in the background.

A map showing the layout of GKN Machinery

Limited.

| The Peco Division produced Peco

injection moulding machines for thermoplastic,

thermosets, and rubber compounds, extrusion machinery

for thermoplastics, and spark erosion machines for

cutting dies and press tools. A machine demonstration

area was built at Cable Street along with a

comprehensively equipped machine development department,

where complete plastics production facilities could be

designed and then manufactured for customers anywhere in

the world. |

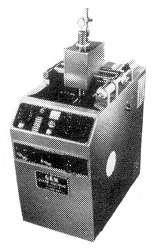

A Peco 25 MR injection moulding

machine. |

|

A GKN 'Unimate' industrial robot. |

The Unimation Division produced GKN 'Unimate'

universal automation equipment, and programme control

systems for capstan lathes and automation. |

| The Components Division produced Bayliss, Jones &

Bayliss motorway and bridge parapet railing, fencing and

gates, and mining support equipment. Early contracts

for GKN Machinery included a 235 ton double-side

trimming shear, capable of trimming plates from

¼ inch to 1½ inch

thickness, and the world's most advanced heavy plate

mill, the biggest of its kind in the country. It could

deliver up to 8,000 tons of standard quality steel plate

per week. |

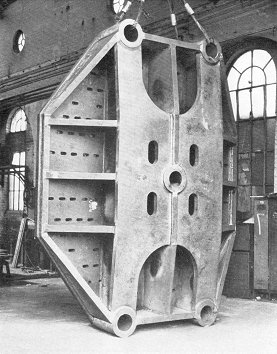

A double side-trimming shear under

construction. |

|

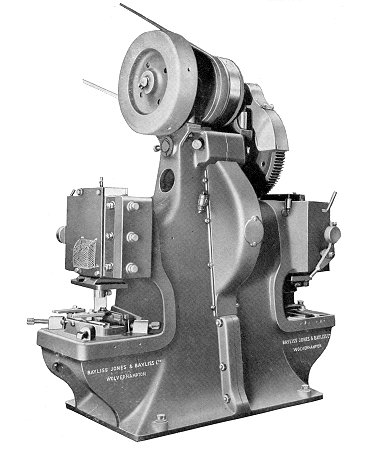

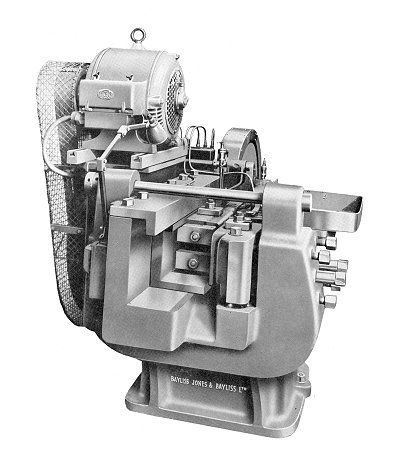

A Bayliss, Jones & Bayliss

double ended press. |

| A Bayliss, Jones & Bayliss

multiple punching and shearing machine. |

|

|

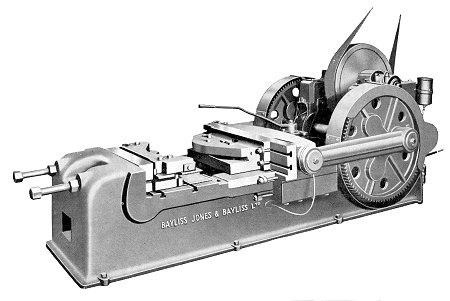

A Bayliss, Jones & Bayliss bar

cropping machine. |

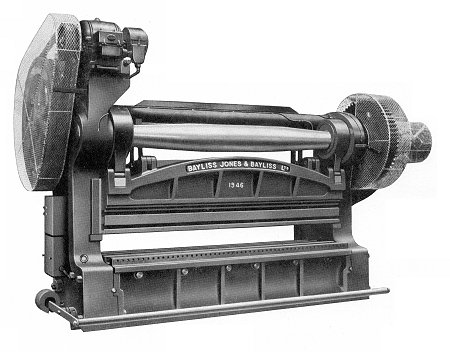

| A Bayliss, Jones & Bayliss

rolling and straightening machine. |

|

|

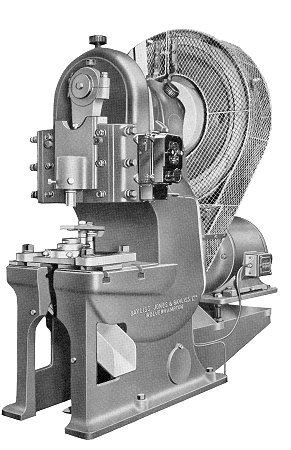

A Bayliss, Jones & Bayliss

horizontal bending and forming machine. |

| A Bayliss, Jones & Bayliss

single end press. |

|

|

A Bayliss, Jones & Bayliss

billet and bar cropping machine. |

| A Bayliss, Jones & Bayliss

roll turning lathe. |

|

| Machining a 36ft.

long, 40 ton casting in the Heavy

Engineering Department. |

|

Under a £1m. improvement scheme a completely new

assembly bay, 75ft. wide was constructed on one side of

the main workshop. It had several cranes installed to

handle loads of up to 100 tons, with a maximum lifting

height of 45ft. The main workshop was also extended to a

length of 425ft.to increase the internal area to 65,000

square ft.

Many large new machine tools were installed, some

featuring a digital readout, which was new technology in

the late 1960s. |

| The heavy fabrication department had facilities for

submerged arc and CO2 automatic and

semi-automatic welding. Other facilities included

profile and straight line cutting up to any size of

plate, and plate thicknesses up to 2ft. The product

range also included power presses,

inspection equipment for steel billets and slabs, welded

chassis and body assembly for fork lift trucks, tool

drawer bars, linkages for tractors and the 'Birfeed'

range of automatic bar feeding and loading magazines.

In the late 1960s the Metal Forming Plant Division

obtained a computer using the I.B.M. Kraus system. The

machine was used for costing orders and to trace the

progression of orders through the works. |

A Model 'C' spark erosion machine. |

The company's newsletter.

Courtesy of Nina McCarthy.

|

Cyril Banton. Courtesy of his

daughter, Nina McCarthy. |

The company's Works Engineer, Cyril Banton retired

in April 1970 after serving 41 years with the company.

He followed in his father's footsteps, who had worked in

the foundry for 40 years. Cyril's son Jimmy also worked

there for many years. Cyril was originally an

electrical engineer until 1963 when his predecessor Bert

Denny retired. Cyril was involved in several large

projects during the modernisation of the works,

including the new rolling mill and the machine and

assembly shop. |

|

By 1970 the rolling mills were run

by James Mills Limited and the Metal Forming Plant

Division were producing sophisticated servo-hydraulic

control systems. One order, worth £250,000 was for a

control system for a large rolling mill for Germany's

most prominent producer of tin plate and cold reduced

steel strip, Rasselstein A.G. of Neuwied/Rhein.

It all came to an end in the 1980s

when GKN decided to close the steel side of the business

and so the works were sold.

This article is based on

the following:

An article written by Helen Priddey, which can be found in the Museum Metalware Hall

on this website.

The History of GKN, volume 2 by Edgar Jones.

Material from Nina McCarthy whose father worked for the

company.

Various Wolverhampton Handbooks.

Bayliss, Jones & Bayliss catalogues. |

|

Return to the

previous page |

|