|

In the early 1700s

the face of Dudley began to change, when

brick-built buildings became more

fashionable. There were large local clay

deposits and a number of improvements in

brick making, including blended clay,

better moulding techniques and more even

firing, which resulted in a greater

consistency, both in size and shape.

Dudley still has

two fine examples of early brick-built

houses, both from the early 1700s. In

Priory Street, then called Sheep Street,

next to the building that housed

Dudley’s museum, is a lovely house

carrying the date 1703 and the initials

of Hugh and Joyce Dixon. They were

married on the 2nd November, 1701, so

this was possibly their first proper

family home. Hugh was the first known

glassmaker in Dudley, who unfortunately

was declared bankrupt in 1713.The house was Grade II

listed on the 14th September, 1949.

The second example,

known as Finch House, is one of the

finest buildings in the town. It is in

Wolverhampton Street, on the corner of

The Inhedge. It has a Queen Anne facade

which carries the initials of the

owners, Joseph and Mary Finch and the

date 1707. The building was Grade II*

listed on the 14th September, 1949. In

1711 the Court Leet ordered that Joseph

Finch must "mend the road leading to the

bounds of the parish towards Gornal

Wood." He was required to mend the road

outside his house in Wolverhampton

Street. His grandson, John Finch, opened

the first bank in Dudley.

Another fine

example of a fine brick building is

Chaddesley House, also in Wolverhampton

Street, on the opposite side of the road

from Finch House. It was built in the

middle of the 18th century of red brick

with a moulded stone door case and

pediment. The building was Grade II

listed on the 14th September, 1949.

A prominent

brick-built building was the old town

hall that stood in the centre of the

market place. It was raised on arches

that provided a useful space beneath for

use by market traders. Sadly the

building became an eyesore. On the 24th

November, 1858, C. F. G. Clark wrote to

the Dudley Times and Express, advocating

its demolition for its acknowledged

nuisance as a public urinal, its

shameful use as a hiding place for

juvenile obscenity and adult immorality.

The building was demolished in 1860.

|

|

The Dudley

Arms Hotel. From an old

postcard. |

There was another fine brick

building in High Street,

overlooking the market place,

which was built in the late

1790s on the site of the old

Rose and Crown. The Dudley Arms

Hotel was very large and plain,

but had a certain dignity. It

was built by a group of

prominent townsmen who formed

the "Building Society" for the

purpose of buying land and

building houses on it for its

members. The initial plan was

to build the Dudley Arms Hotel.

Subscribers took £50 in shares

in the new society and a capital

fund was accumulated. Not a

great deal is known about the

activities of the society, or

how many houses were built from

its funds.

There was a great deal of

interest in the scheme to build

the Dudley Arms, which resulted

in an impressive building that

soon became the most popular meeting

place in Dudley, and provided the town

with a handsome assembly room. It was also

the main coaching inn in the town.

The hotel finally closed in May 1968 and

was soon demolished. |

| During the 18th

century, the whole character of the area

changed, as many of the ancient timber

framed houses in the town centre were

refaced in brick, so that by the end of

the century it all looked very

different.

For many years horse fairs were

held in the market place. It

began on September, 1685 when

King Charles II gave permission

to Edward Baron Ward to hold two

fairs annually, on September

21st and April 27th, each

lasting two days. Horses, sheep,

cattle and other merchandise

were sold, for which tolls were

charged. By the early 18th

century there were three fairs

annually, held on April 27th,

July 25th and September 21st.

The tolls were extremely small,

only 4 pence per horse sold, so

little money was made. In July

1703 the profit was only one

guinea. On September 21st, 1792,

only 2 shillings was received in

commission for sale of horses.

Later there were four annual

fairs, held in March, May,

August and October. The fairs in

March and August were toll-free. |

|

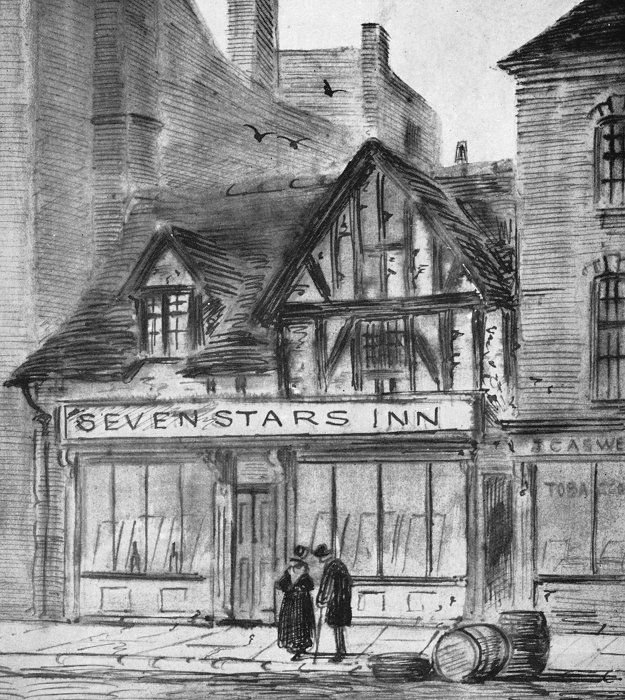

The Seven

Stars Inn that stood in the

Market Place. A drawing by Paul

Braddon. |

| The Court

Leet For several

centuries, Dudley was governed by

the old manorial court, known as the

Court Leet, which had jurisdiction

over civil affairs including minor

criminal matters and

petty offences.

The earliest records of court

proceedings are from 1732 for the

town centre and 1701 for the

surrounding

areas. The Court Leet continued

until 1865, but was largely

superseded in 1791 by the Town

Commissioners, formed under the

terms of the Dudley Town Act, passed

in Parliament in May, 1791.

The Court Leet

met twice yearly, in May and

October. Separate juries were

sworn-in for the old borough and the

other areas until 1798, when they

were combined. The meetings were

held at a number of locations

including The Swan Inn, the Town

Hall and the Dudley Arms Hotel.

Anyone summoned to attend a meeting,

and failed to be there was fined

quite heavily. In October 1787 fines

varied from 1s. 6d. to 5 shillings.

The juries

appointed the town officers. Each

year one person was elected as

bailiff, the head of the borough. In

the following year he would be

Mayor. Other appointments included a

sergeant and two constables to look

after law and order, two searchers,

leather sealers, ale tasters and two food inspectors

called flesh and fish tasters.

Fines were

handed-out for a breach of the

lord's assize of bread and ale, and

speculation in farm products sold in

the market. In 1732 no one was

allowed to sell butter in the market

before 1 o’clock, and anyone

bringing corn to the market could

not sell it elsewhere before 12

o’clock. Failure to comply resulted

in a fine for 13s. 4d. Juries also

ensured that the ancient forest laws

regarding the number of animals kept

on a small holding and the removal

of timber were within legal limits.

Other considerations included the

provision of a ducking stool for

punishments, the regulation of "plays and

games" in the Town Hall, the repair of

the pound, and the keeping of Sunday

observance.

The repair of roads and

footways was not forgotten. Orders were issued to

private individuals and the

parochial supervisors of highways,

to repair the streets, especially

the main roads leading in or out of

the town. Failure to comply would

result in a heavy fine of up to

£1.19.11d. On the 23rd April, 1741,

the supervisors of highways were

ordered to fix some stepping stones

across a brook, and in October 1786,

Mary Finch was ordered to remove

some recently built steps from her

house and Mr. Green's house, which

extended too far into New Street.

They were to be removed within

fourteen days, or she would have to

pay a substantial fine. Every

citizen had to abide by the court

rulings, no one was exempt, not even

George Jones, who had been mayor of

Dudley in the previous year. In

the October court in 1787 he was ordered

to keep open a pathway through Yokes

Park to Blowers Green where people

were in danger of falling into a

water pit. He was ordered to erect

posts and rails alongside the path

within six weeks, or pay the maximum

fine. |

|

Dudley

High Street in 1812 by Paul

Braddon. |

|

Sanitation was

also scrutinised by the court. Heavy

fines could be imposed for

accumulating rubbish in the main

channels after market days or for

the illegal diversion of open and

unsanitary watercourses in busy

parts of the town, or the discharge

of sewage into the streets.

The court also kept an eye on house

building, particularly because of

the fear that more houses could

increase the number of poor people

that the parish had to maintain. In

1733 John Crump was ordered to pull

down a new building which he had

recently erected on unused land in

Netherton, near to a goat house.

This had to be done within one month

or he would have to pay a fine of

thirty three shillings.

Although the Court Leet had the

necessary powers to deal with the

affairs of a small community, Dudley

began to change from a rural area

with a relatively small population

into an industrial area with a

greatly increasing population. The

Court Leet did not have sufficient

powers to adequately deal with the

enlarged population and enforce the

minimum provisions that were

essential to the developing town,

including sanitation, cleansing and

policing.

By 1790 the streets were still

narrow, largely unpaved with many

obstructions and manure and filth

had been allowed to collect there.

Houses were still not numbered,

streets were unlit, the water supply

was inadequate, and the only police

were the two constables and a

sergeant appointed by the court. There

was little jurisdiction so disorders

were commonplace.

Because of the intolerable

conditions in the town, the Dudley

Town Act was passed in 1791 which

authorised Commissioners to levy a

rate to enable the essential

improvements to be carried out. The

Court Leet continued to meet until

the 28th December, 1866, but after

the formation of the Town

Commissioners it seemed to lose

confidence in itself and more often

than not, just expressed opinions

rather than dealing with problems

and issuing fines. It slowly became

obsolete. |

|

Government

by the Town Commissioners

1791-1852

As already

mentioned, in 1791 Parliament

passed the Dudley Town Act which

led to the formation of the Town

Commissioners, Dudley's local

government which remained in

power until 1852.

All

ratepayers occupying or owning

property of a certain value

automatically became

commissioners after swearing an

oath. This was fatefully flawed

because of self-interest. It may

have seemed reasonable at the

time, but it did not lead to

effective local government in

the interest of all the

inhabitants. The middle class

ratepayers tended to keep the

rates down and had little

support for social improvements

to help the poor, which would be

mainly paid for by better-off

ratepayers.

The

sanitation and health conditions

continued to be shocking, but

the Commissioners could not

ignore the inadequate water

supply and the poor police

protection. They did

occasionally make half-hearted

efforts to seek further powers

to improve the town, but only

due to public opinion when it

was outraged by cholera or other

epidemics.

The

Commissioners carried out some

improvements, but their

financial resources and legal

powers were inadequate to deal

with their wide ranging

responsibilities. Their efforts

were often overcome by

self-interest on the part of

local businessmen or

industrialists. In 1852 Isaac

Badger successfully fought

against an application for the

Health of Towns Act for Dudley,

even though 70 percent of

Dudley's inhabitants died before

the age of 20.

The

situation was not helped by the

fact that the Commissioners were

jealous of other bodies carrying

out the necessary work that they

would not do themselves. They

were resentful at the

incorporation of the Dudley

Waterworks Company by an Act of

Parliament and they fought

against the application of the

Constabulary Bill to Dudley.

The

Commissioners met irregularly at

the Dudley Arms Hotel and

decided matters by a majority

vote of all present. A chairman

was appointed for each meeting.

The minutes were signed by any

or all the Commissioners

present. Many meetings had to be

adjourned because the minimum

number of five Commissioners did

not attend.

The

Commissioners were empowered to

appoint officers including two

clerks, a treasurer, a surveyor,

and a scavenger, whose role it

was to collect rubbish in a

cart, weekly, from the

inhabitants and take it away. He

had to let people know when he

was coming by ringing a bell or

shouting loudly.

The

Commissioners had the power to

ensure that people were not

allowed to drive any wheeled

vehicle including wheel barrows

on public footpaths, sell horses

and cattle on footpaths, or

slaughter them there. Owners of

animals and cattle were not

allowed to let them freely

wander the streets and large

dogs had be kept under control

and securely muzzled. People

were not allowed to light

bonfires there, or let-off

fireworks. Any of the offences

would be subject to a fine of

five shillings. Bull-baiting or

bear-baiting was not allowed and

was subject to a fine of forty

shillings.

The Act

gave the Commissioners the power

to whitewash the houses of the

poor at the Commissioner’s

expense, but this seems to have

been ignored. The Commissioners

also had the power to appoint

watchmen to control the lawless

conditions in the town, but only

the minimum number was appointed

and their work was largely

ineffective. The Commissioners

used their power to provide pumps to

help maintain the water supply,

but this remained inadequate

until the incorporation of the

Borough in 1865. |

Stone

Street in 1925. The building

on the far left was a malt

house which was demolished

to make way for the Fountain

Arcade. From an old

postcard. |

|

On the 20th

August, 1792 the Commissioners

decided that a sufficient number

of oil lamps with lamp irons

would be fitted at the corner of

the main streets and that an

advert would be published for a

person to supply the lamps with

oil during the forthcoming

winter. At the same meeting,

the Commissioners ruled that

houses in the following streets

were to be numbered by painting

large letters in a conspicuous

place. The streets were High

Street, Wolverhampton Street,

Stone Street, Queen Street, Hall

Street, New Street, Castle

Street, Fishers Street,

Birmingham Street, King Street,

Mill Street, Priory Street and

Tower Street.

The amount

of the annual rate levied by the

Commissioners was defined in the

Act. Two shillings in the Pound

was paid by occupiers of houses,

granaries, malt houses, glass

houses, or other buildings, and

for yards, gardens, and land

valued at Five pounds or more.

At a

meeting on the 4th December,

1812 the Commissioners decided

to sell the manure lying near

the castle wall to Mr. Parker

and also to sell the manure

arising from the sweeping of the

streets to Samuel Smith. On June

the 26th, 1813 they appointed

Mr. Stokes as inspector

nuisances and annoyances in the

town, at a salary of £5.5s.0d. a

year.

On the 21st

February, 1821, Messrs. Barlow

informed the Commissioners of

their intention to obtain an Act

in the present Session of

Parliament for incorporating the

Town of Dudley Gas Light

Company. The Commissioners’

clerk was ordered to take steps

to protect the interests of the

Commissioners who were more

concerned with preserving their

own powers than implementing

them.

On the 22nd

November, 1827 the following

people were appointed as

watchmen at a salary of twelve

shillings per week: William

Baird, Joseph Southall, James

Farren and Thomas Neale. At the

same meeting, James Robinson was

appointed superintendent of the

watchmen at a salary of five

shillings per week. He was under

the direction of Mr. Joseph

Cooke, Chief Constable. Each

watchman was provided with a

suitable uniform, a lantern

and a rattle.

On the 12th

September, 1828, the first

complaint against the watchmen

was made. James Farren and

Joseph Southall, two of the

watchmen were accused of

negligence and drunkenness. It

was ordered that Mr. Cooke was

authorised to discharge them if

he thought that was the proper

thing to do. In

future he was empowered to

discharge or suspend any

watchman for drunkenness or

improper conduct and to appoint

others in their places.

On the 6th

May, 1834, it was ordered that a

place be acquired for storing Fire

Engines and that Richard Paskin,

be appointed as engineer to

take care of them at an annual

salary of eight pounds. Also

that twelve firemen be paid the

sum of one pound each per year.

On the 16th

June, 1848, it was ordered that

the cattle market in fair days

be confined to the north side of

Wolverhampton Street, both sides

of Priory Street and Hare Pool

Green and that no cattle be

permitted to stand on the South

side of Wolverhampton Street.

On the 20th

October, 1848, it was

unanimously resolved that five

of the Commissioners would form

a committee to carry out the

provisions of the Nuisances

Removal and Diseases Prevention

Act, 1848, and that they

continue in office for one year.

On the

9th January, 1851, it was

ordered that the Common

Lodging Houses Act, 1851 be

put in force and that the

keepers of all common

lodging houses and beer

shops within the limits of

the Town Act were required

to register them and that a

register of the keepers

would be provided and

kept at the clerk’s office.

As already

mentioned, the Commissioners

consisted of some of the

wealthier members of the local

community who were more

concerned about keeping down the

rates, rather than helping the

poorer members of society, many

of whom lived in terrible

housing. Everything was done on

the cheap. To save money the

Commissioners only appointed 9

watchmen who were under the

control of the constable,

appointed by the Court Leet. The

small number of watchmen were

incapable of patrolling the

hundreds of taverns and beer

shops in the area, so

drunkenness and crime went

unchecked.

A public

inquiry held in 1852 revealed

that Dudley's health and

sanitation was the worst in the

country. The inquiry revealed

the failure of the Commissioners

to remedy the terrible

conditions in the town and so

they were replaced by the Dudley

Local Board of Health.

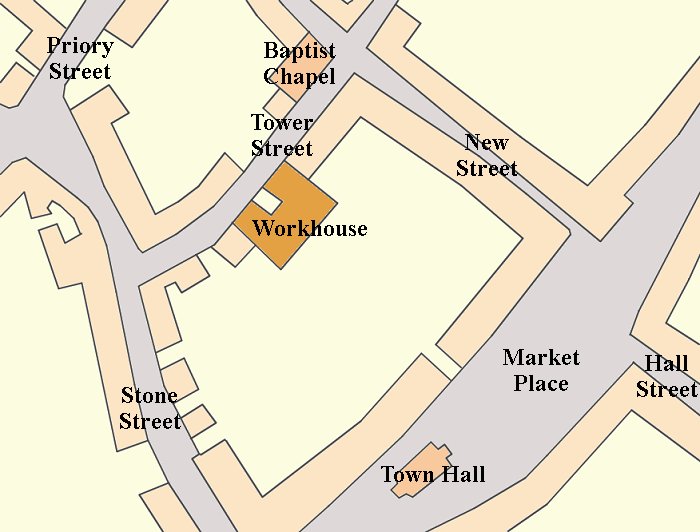

By 1777

Dudley had a workhouse in Tower

Street (formerly Pease Lane), that could accommodate up

to 100 people. It continued in

use until the 1850s, long after the creation of the

Dudley Poor Law Union in 1836,

which was established under the

terms of the 1834 Poor Law

Amendment Act. |

|

The

location of Dudley's first

workhouse. |

| The 18th century was a

century of change, from a small

rural town to the beginnings of

a large industrial one. By the

beginning of the 19th century

the population was over 10,000.

It is listed as 10,107 in the

1801 census. |

|

|

|

|

|

Return to Churches

and Religion |

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to the

Nineteenth Century |

|