|

Civic and Public Buildings

In 1832

and 1867 constitutional reform had increased the size of the

electorate at national level, with the result local authorities

increased in power and function as the 19th century progressed.

Local government had been reformed (not to say largely created)

by the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835 that swept away the

old system based on corruption and nepotism, with a mainly

uniform pattern of elections and representatives. Councillors

were to be elected for three years by all resident ratepayers;

one third would stand down every year and the council would also

elect one third of its number as Aldermen who would serve for

six years. The change in the conditions of the towns in the 19th

century was very much the result of local government activity,

especially where it was given the initiative from central

government. Many local authorities took advantage of legislation

such as the Electric Lighting Act or the Artisan’s Dwelling Act

to improve their towns, though very few did so with the vigour,

foresight and commitment of Birmingham’s Joseph Chamberlain with

his “Civic Gospel”.

It was

the construction of Birmingham Town Hall in 1829 that sparked

off the spate of civic building in Britain. Newly enfranchised

towns and cities displayed their civic pride in majestic,

imposing and sometimes downright vulgar buildings, the apogee

(or nadir) probably being the Town Hall at Colchester.

Sometimes the term Town Hall covers both administrative offices

and a hall for social occasions such as in Walsall; a building

quite separate from the administrative offices as at Birmingham

or a purely legal and administrative building as at

Wolverhampton. The oldest town hall in Wolverhampton was in High

Green. The present one is on the site of the Old Town Hall built

in 1856. It soon became manifest that the old Town Hall in North

Street and the police barracks in Garrick Street were quite out

of date and very inconvenient. A certain Alderman Fowler pointed

out that there was a large piece of unoccupied land at the back

of the Town Hall, which could be adapted for the construction of

a new building in keeping with the town’s newfound dignity. In

the event what should have been a dignified and stately progress

to a new civic building took on an element of farce.

The

design for a New Town Hall for Wolverhampton was put out to

competition and attracted nineteen competitors, including the

local architect Bidlake. This competition did not run smoothly,

with complaints and fits of pique from the competitors. In the

competition £100 and £50 was offered for first and second prize,

on the condition that the realisation of the designs could be

carried out for £15,000. The first prize was initially awarded

to Bidlake, with Bates of Manchester second. The designs were

forwarded to the notable architect Waterhouse, who was acting as

adjudicator, to see if they could be carried out for £15,000. He

reported that Bidlake’s designs would cost £25,000, with another

five or six hundred for a tower, whereas Bates’ would cost about

£25,000. Accordingly both designs were rejected and two more

chosen. Architects then went in for even fancier names than

modern housing developments. Two of the designs chosen were

“Salve”

by Christopher Wray of London and “Perceverance Urices”

by Lloyd of Bristol. Once again the proviso was that the designs

had to be carried out for under £15,000. Whether the borough was

short of money or just wanted the work done on the cheap is

unclear. The committee found that none of the plans chosen could

be carried out for £15,000 and so obtained fresh designs from

Bates of Manchester, the Wolverhampton architect Mr. Veall,

Griffiths of Stafford and Mr. Lloyd of Bristol, all of whom had

been previous entrants. Bidlake, in what appears to have been a

bout of hurt pride or possibly pique, refused to submit a second

design. Finally the designs of Bates were accepted.

|

|

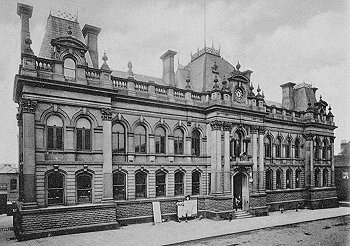

Wolverhampton Town Hall. |

When it came

to actually building the Town Hall, there were once again

problems. There were a large number of tenders submitted and the

one accepted was that of Mr. Robinson of Manchester. However

after the terms were agreed the plans were changed to

incorporate more features. Robinson, justifiably aggrieved,

asked if he could withdraw, a request that was allowed. In the

new tender the lowest was that of Horsman the local builder. |

| The Town

Hall was opened with great ceremony in 1871 by the Lord

Lieutenant of the county but the rejoicing over the New Town

Hall was short lived, for very soon after there were numerous

complaints about the building, not least that the acoustics in

the council chamber were diabolical. This was a cause of

considerable irritation; for the building had in the end cost

almost double what it should. The building was badly

constructed, so much so that a prisoner in custody for a serous

offence had actually been able to scale the walls of the

exercise ground. Also the Borough Police Court and the Quarter

Sessions Court were so badly designed in regard to their

acoustic properties that the Magistrates, Recorder and Jury were

not able to hear the evidence brought before them. In the

council chamber there was a notorious echo preventing the mayor

from hearing the councillors and the press from hearing either.

Attempts were made to improve things by hanging flags around the

chamber. For a time a large canvas sheet was hung below the

level of the ceiling, which though partially effective, was

hardly aesthetically pleasing. The Town Hall was extensively

re-modelled in 1903. Originally the vestibule ended where the

present stairs begin. Here there was a blind arch, in front of

which was the statue of Thorneycroft, Wolverhampton’s first

mayor.1

Many

Town Halls derive their designs from the Italian Renaissance or

the Jacobean, but architects also drew upon the architecture of

France. In designing Wolverhampton Town Hall. Ernest Bates, who

submitted the winning design, used French style wholesale. There

is a trio of mansarded pavilions that provide an effective

substitute for a tower. It has a rusticated lower course and

fifteen bays created by pilasters. However, like so many

prestigious but essentially workaday buildings, only rather

functional and not very prepossessing brick backs the impressive

façade. The vestibule of the building is especially imposing.

There are cells for prisoners and at the rear an impressive

courtyard that backs on to the police offices in Red Lion

Street.

At the

opening of the Town hall it was stated in regard to the

usefulness of the building, “nor is architectural beauty

sacrificed to utility, but both are so well combined that is at

once an ornament to the town and a most excellent building for

the transaction of the public business”

*

*

*

*

*

In 1827

there was a small shop in King Street opened as a library for

the gentry. In 1835, many of the leading people in the town

thought that this same privilege should be extended to the

middle classes such as clerks, shop assistants and others;

accordingly they formed a company and subscribed about £1,000

towards building a Mechanic’s Institute in Queen Street as a

library and lecture hall.

The

growth of literacy, due largely to the Education Act of 1870,

resulted not only in an expansion, one might say creation, of a

popular press, but the growth of public libraries and reading

rooms. However circulating and subscription libraries had long

existed. The most popular were subscription libraries and

Wolverhampton had its own in Waterloo Road that was built to a

design by Edward Banks.

In 1855

the Free Libraries Act was passed allowing authorities to

provide libraries out of the rates. The act was not mandatory

but permissive, as was so much 19th century

legislation that affected towns. There was an attempt in 1860 by

Councillor C. B. Mander to adopt the Act for Wolverhampton.

Although the proposal was carried, the idea of increasing the

rates by one penny in the pound to pay for the library (and

incidentally to pay for the accumulated debts of the School of

Art), caused an outcry from disgruntled ratepayer’s and at a

public meeting the council was forced to back down. In the

following years the Working Men’s College had closed down, as

had the Mechanic’s Institute. At a meeting to wind up their

affairs it was resolved to hand over the three thousand books

and furniture to the corporation as a start towards a Free

Library.

The

culmination of Wolverhampton library service was the building of

the present library. The laying of the foundation stone was a

grand affair. The council had granted £1,600 to meet expenses

and £1,000 came from the Carnegie Trust. An address was read,

the Bishop of Lichfield gave prayers and afterwards Theodore

Mander gave a splendid luncheon to a thousand people in a large

tent. The Duchess of York gave prizes to children from the Royal

Orphanage.

|

|

Wolverhampton Library is a fine building dating from 1900-1902

built to a design by E.T. Hare, who won a competition sponsored

by the Borough Council. It stands on the corner of Garrick

Street and Cleveland Road. This was once the location of two old

buildings, the most interesting one being the previously

mentioned Elizabethan Old Hall, which was demolished to allow

the building of the library; the building is still remembered in

the street of that name. It is fitting that such a grand

building should be the final summation of a long trend in

Wolverhampton to provide reading for all classes of society.

|

Here the

many eclectic details of the building can be seen. Note

especially the lovely bowed window overlooking Cleveland Street. |

|

The end

of the century saw a number of public buildings designed in a

highly decorated Free Style and Wolverhampton Library is one of

the best, with its fine light reading rooms. The details are

eclectic, including Jacobean as well as Baroque features. The

library makes interesting use of its difficult corner position

with a fine façade built of yellow terracotta. It has an angled

entrance loggia surmounted by a cupola. Around the walls,

moulded into the terracotta are the names of various literary

luminaries – Byron, Shakespeare, Chaucer, Pope, Milton and

Dryden. By about 1860, terracotta had replaced stucco as the

fashionable material; it was not a new material, but it began to

be used extensively and was appreciated for its red and yellow

appearance and (so it was claimed) great durability.2

Above the entrance is the Royal Coat of Arms in moulded

terracotta with the legend “To Commemorate the Sixtieth Year of

Queen Victoria’s Reign”.

The

interior of the library must be the finest piece of secular

architecture in town, but it would be better appreciated if it

were not for all the books that get in the way. Downstairs, to

the left of the vestibule, graceful Corinthian columns create

four wide bays. A wide curving staircase3 is

lit from above by a dome embossed with the town’s Coat of Arms.

Upstairs, in the room occupied to the left, there is a fine

glass dome in the roof and, although it can hardly be seen, high

wooden panelling around the walls. One small interesting feature

is the small oriel window at the rear of the room. This room was

once used for lectures and recitals and it is a pity that the

shortage of space in the Central Library no longer allows this

room to be kept free and its beauties better appreciated. The

reference section has recently been renovated and whilst the

shelves were out, the room could be better appreciated.

Art

galleries and libraries usually go together the latter very

often serving the purpose of the former. However Wolverhampton

Museum and Art Gallery dates to the decade before the library

being built between 1883 and 1885 to a design by the Birmingham

architect J.A. Chatwin. The Art Gallery occupies a prominent

place in Lichfield Street, which itself lies roughly on the

route of Kem Street, which together with Burg Street was

probably Wolverhampton’s most ancient street. Modern Lichfield

Street was extended beyond Queen Square as part of the

redevelopment and slum clearance that took place after the

passing of the Artisan’s Dwelling Act of 1875. The gallery was

officially opened on the 30th May 1884 for the

Wolverhampton and Staffordshire Fine Arts and Industrial

Exhibition.

The

origins and impetus to the building of the Art Gallery were a

little unusual. Alderman Jones, during the period of his

Mayoralty, took a deep interest in art teaching, especially the

application of artistic principals to the manufacture of the

town. In 1881, Alderman Jones presented £500 to the town “as

the nucleus of a fund to provide works of art manufacture

applying to various trades of the town”. This gift

occasioned the following letter:

Dear Mr. Mayor,

I

see you have started a subscription for an Art Gallery in the

town. I am therefore prepared to erect and present to the town a

building of the value of £5,000 upon the following conditions: -

First, the town to provide a suitable site with provision for

enlargement. Second, that you form a committee, consisting of

yourself, the Rector, and Sir Rupert Kettle, for the purpose of

maturing the plans, say whether a museum should be associated

with it, and for the purposes of inducing a gentleman in the

neighbourhood to contribute works of art in painting, sculptor

etc, and when you have promises to the extent of 10,000 and are

otherwise ready, I am prepared to begin building. Third, it must

be a strict condition that no other person, except yourself,

know the name of the giver. Of course the secrecy I require does

not prevent you mentioning the offer before you vacate your

office.

Yours very truly

XYZ4

The

letter was written by Philip Horsman who was a notable

philanthropist to the town and who also gave money towards the

building of the Eye Hospital. In the entrance hall to the Art

Gallery is a memorial plaque and portrait of Horsman cast in

bronze that shows a rather dreamy, bearded man with his sights

set firmly on the next world. He founded a building firm in 1860

and was later joined by a partner named Wilcock. The firm was

responsible for many of the notable buildings in the town

including the library, Town Hall and Art Gallery. In the garden

attached to the Art Gallery is a fountain to the memory of

Horsman, erected by public subscription. The unveiling took

place in 1896 by the Mayoress Mrs. Mander.

The

building is a monument to civic pride and was opened with great

ceremony and display. The best description of the building comes

from a contemporary at the opening ceremony:

“Though but two storeys in height, it presents an imposing

appearance. The façade towards Lichfield Street is 90 feet long,

while that towards St. Peter’s is 66 feet. The style of

architecture is mixed Doric and Ionic. The material used is Bath

stone. Three fine red granite pillars support the portico on

each side of the man entrance. Along each façade of the building

a frieze runs, containing various allegorical representations of

the arts and sciences. The very most is made of the interior of

the building. There is a handsome vestibule, beyond which is a

lofty hall, out of which open three spacious rooms which are to

be devoted to the Art Gallery. Ascending a stone staircase, four

rooms are reached, two of which, running parallel to each other,

are exceedingly fine. These are occupied by pictures, and it is

expected that they will be permanently devoted to the same use.

The light, particularly in the upper rooms, is excellent. Both

gas and electric light are provided, and the building is

generally the beau ideal of a Fine Arts Gallery”.

The

above-mentioned frieze is one of the most striking aspects of

this building and was executed by Mr. Carter from the Cheltenham

firm of Boulton and Company. The carving is in Portland stone

and represents the Arts and Sciences. This frieze has much in

common with that around the Albert Memorial in London opened

some years before. Victorian buildings were meant to be read in

a way that modern ones are not; the Albert Memorial is a mass of

cultural and historical references that would have been readily

understood by contemporaries. The figures on the Art Gallery,

though not so numerous or elaborate point to the images of the

building and the Victorian age that the designer was trying to

convey. They are figures of the past, historical, symbolic and

allegorical, which the Victorians saw as the forerunners and

embodiment of their own age.

|

Art and beauty are personified by graceful

female figures on panel three to the left of the main entrance. |

There are four panels;

two facing Lichfield Passage and two either side of the entrance

facing Lichfield Street. Panel one; reading from left to right,

shows the fruits of industry. There are scenes of glass blowing

and engineering workers with large hammers. One figure holds up

a large lock, a potent symbol of the town’s premier industry.

Other figures are at work on delicate pots.

|

| On the far

right of the panel, one figure personifies design. The second panel

is dedicated to discovery in the arts and sciences. Classical

figures on the right are engaged in geometrical drawings. Ǽsculapius

the god of healing is shown with his serpent entwined staff. In the

centre a figure (Copernicus?) stands in contemplation of a globe,

whilst a figure that we take to be James Watt holds the governor

mechanism that so improved the performance of the steam engine.

Behind him is the Sun and Planet system that did so much to allow

the steam engine to be used for a wide variety of industrial

purposes i.e. converting vertical to rotary motion. Panel three is

if anything the most graceful and the only one incidentally that

shows a female figures. One holds a sign carrying the words “Truth

and Art”. In panel four an Assyrian figure stands in front of a

winged beast whilst Michelangelo is at work on the statue of Moses.

At the end, ironically on such a classical building, a religious

figure holds a Gothic building. |

| The entrance

is grand and imposing with either side granite columns, these too

were the gift of the builder. They support a balcony above which

there are further pillars. From the entrance hall is a flight of

stairs leading to the upper story. |

Progress in the Sciences and Navigation. |

| The most

impressive feature of this staircase is the wooden oak panelling

that covers the walls to a considerable height, with a graceful

carved border inlaid at first floor level. This can be better

appreciated now that the large paintings that once hung here have

been removed. The gallery contains a large number of paintings by

19th century artists. |

|

The fountain erected in honour of the

philanthropist and benefactor of the art gallery, Mr. Philip Horsman. J.P. |

The fountain

in the garden that is dedicated to the memory of Horsman is dated

1894 and consists of six dolphins interspersed with bulrushes,

supporting a bowl with their tails. Above, four cherubs alternating

with carved lilies and fish-like grotesques support a smaller bowl.

The gardens, which

have now been softened by the addition of shrubs and trees, were

originally laid out in a highly formal manner, the surrounding iron

rails adding to the effect. Until recently, forlorn stubs of these

said iron rails were a painful reminder of what had been lost but

recently they have been replaced to great effect. |

|

Attached to the Art gallery is the School of Art. There had

previously been a Wolverhampton School of Practical Art, the

first in the country to be erected for that special purpose.

Although housed in a large building designed by Edward Banks and

liberally subscribed by C.B. Mander, the building was

“indifferently appreciated”.

The building can easily

pass notice but the Scottish turret is a fine and notable

feature. The brick work oblique to St. Peter's Close also shows

what can be done with restrained effect when using brick.

|

The "indifferently appreciated" original Art

School, but a little gem of a building by Edward Banks. |

|

The building of the Art gallery acted as a spur to the committee

of the School of Art who decided to dispose of their building in

Darlington Street and build a new one in larger premises in

conjunction with the Art Gallery. The council originally gave the

land for the purposes of making any necessary extensions to the Art

Gallery. Horsman and Co. built the new Art School. It had numerous

rooms including a light and shade room for Machine Building

Construction. Numerous classes were run for the benefit of those

“artisans” who wished to improve themselves. It is an attractive

building with a corner tower surmounted by a conical roof, thus

giving a Scottish feel to the whole. In the roof there are a number

of gable windows. Although built in brick there is some restrained

decoration.

*

*

*

*

*

|

|

The former Post Office.

|

The building

in town that makes even more use of terracotta than the library is

the Post Office, of which now no part is used for that purpose. It

is the work of the Government Architect Sir Henry Tanner who was not

highly regarded in his day. The Penny Post had been established in

1840 by Rowland Hill (who lived in a farmhouse on the site of the

present Horse Hill Drive off the Compton Road, and was married in St

Peter’s church in 1827) and although the new scheme was regarded as

foolish and did in fact lose a great deal of money, the new system

spread rapidly throughout the country. The result was much Post

Office architecture, not least the pillar-boxes designed by the

novelist Anthony Trollope.

Despite Tanner’s low

standing among his brother architects, Wolverhampton Post Office

is a most interesting building, far more so than the one in

Birmingham that he also designed. Part of its attractive nature

is the contrast between the yellow terracotta and the warm red

brickwork. |

| The front

elevation is most attractive but would be better appreciated if it

could be seen from a little further back. There is an impressive

entrance with two Corinthian pillars. Above the entrance is the date

supported by two lions. On a level with the balustrade is a recessed

space containing the Royal Coat of Arms. There are two pointed

gables and, surmounting the whole, a cupola. There is wealth of

swags and mouldings. The Royal monogram is repeated above each

window in the bottom storey. |

|

One of

the grandest and most forbidding pieces of public Victorian

architecture in the town is that of the Wolverhampton and

Staffordshire General Hospital situated in Cleveland Road. The

building owes its origins to an accident which befell a Mr.

George Briscoe who broke his leg whilst dusting a picture.

Whilst incapacitated his thoughts turned to the poor, who did

not have the benefit of his surroundings when taken ill. After

recovery Briscoe contacted Mr. H Rogers and together they

founded the present institution. The hospital is built in the

Italian-Doric style. Once again the building is erected from a

plan by Edward Banks. At the time of its building the Royal was

described as a “large and handsome building of red brick with

stone pilasters, columns and window dressings and is pleasantly

situated in Cleveland Road nearly opposite the new cattle

market…the rooms, wards, staircases, etc, are well-lighted and

ventilated and the whole building reflects much credit on the

skill of the architect, Mr. Banks”.

|

The Royal Hospital. |

| The cost of

building the hospital was £15,000, raised by public subscription and

supported by public contributions.

“There are twelve

gentlemen who constitute the board, meetings being held once a

week; annual sermons are preached in its behalf in all places of

worship in the town”.

The Eye

Infirmary too contains Victorian work. It was established in

1881 and the new buildings, erected to a design by T.H.

Fleeming, are in a simple Gothic style with two spired turrets.

The in-patients department was erected principally at the cost

of P. Horsman. The hospital was supported by voluntary

contributions.

The

loss of the Victoria Nursing Institute in the 1970s was a sad

blow for it was a fine building with much terracotta

embellishment.

|

The Hogshead public house, formerly the Vine

Inn. Behind it is the Headquarters of the

3rd Battalion of the South Staffordshire Regiment. |

We have seen

the imaginative use made of terra cotta, but brick could also be

used in an attractive an imaginative way. A good example of the

imaginative use of brick is the range of buildings that occupy the

corner of Broad Street and Stafford Street. These are the

Headquarters of the 3rd Battalion of the South Staffordshire

Regiment, erected at a cost of £8,000. They form an attractive range

in the early Gothic style and were designed by Daniel Arkell of

Birmingham. Originally the ground floor contained an orderly’s room

and stores. |

| The drill

hall was 184 feet by 76 feet, with a stage at one end and a gallery

at the other. The building range also appears to incorporate the

Vine Inn whose sign can still be seen in brick over the entrance in

Stafford Street, so much so that a cursory glance makes the whole

look like one range. Closer inspection shows that it is of a later

date. The inn was closed for a number of years but has now once

again reopened as licensed premises but under a different name.

Also in

Stafford Street is a rather mundane range of buildings but they

are distinguished by one rather elegant decorative feature. On

the corner building facing the University is white painted

plaster work with the date 1898

For

such a large and important town, Wolverhampton is remarkably

light on public statuary. Until fairly recently there was only

the statue of Prince Albert, but previously there was also a

statue at Snowhill to Charles Pelham Villiers. Although this

statue was moved and now graces West Park, it seems fitting to

include it. The statue, the work of the London artist W. Theed

is of heroic proportions, being 9 feet high and carved from

Sicilian marble. Villiers represented Wolverhampton as its M.P.

for sixty years and was one of those M.Ps who campaigned for the

repeal of the Corn Laws. The statue was unveiled on the 6th

June, 1879.5

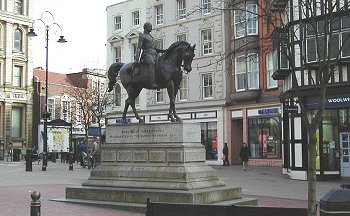

Lastly, the story

concerning one of the most famous sights in Wolverhampton, the

equestrian statue of Prince Albert in Queen Square, which was

the object of the Queen’s visit as recorded in the prologue.

Whilst Mr. Underhill was Mayor in 1862, there was a strong

desire to provide a memorial to Prince Albert. It was decided to

erect an equestrian statue, life size, as soon as subscriptions

came in. The work was placed in the hands of Mr. Thorneycroft of

London and the work took him four years to complete. During the

construction of the statue, Queen Victoria visited

Thorneycroft’s studio to ensure the exactness of the drapery of

the figure. She lent the sculptor not just the uniform worn by

the prince, but also his horse. This interest in the progress of

the statue was no doubt one of the reasons that led the Queen to

attend the unveiling personally. The Memorial Committee erected

a granite pedestal in Queen Square and the task of casting the

bronze was put in the hands of Messrs Elkington and Co. of

Birmingham. |

|

The

inherited story has always been that the sculptor committed

suicide after the unveiling, when it was pointed out to him that

a horse, supposedly, cannot adopt that stance without falling

over. The story is recounted by Phil Drabble in his passionate

book on Staffordshire:

|

The statue of Prince Albert in Queen Square. |

|

“In Queen Square is the statue of a man on a horse about which

there has been a good deal of controversy. The man is Prince

Albert, and his horse has both legs striding forward on the same

side, like a camel. People said that no horse ever had such an

action. They even said the sculptor had committed suicide when

told what he’s done”.6

The

statue is about 9 feet in height, or with the pedestal, nearly

16 feet. The Prince Consort is represented in the uniform of a

Field Marshall, the idea of military dress being the Queen’s

own. Perhaps appropriately for an equestrian statue, Albert has

had a peripatetic existence having occupied four spots in the

last thirty years; for a time he was a little farther down the

Square majestically standing guard over the public toilets.7

Notes:

| 1. |

This

statue of Thornycroft, which was sculpted by Thorneycroft,

had originally been placed over the family vault, but after

exposure to the weather had shown signs of wear. When the

new Town Hall was completed, relatives gave permission for

the statue to be placed in the vestibule. |

| 2. |

Terracotta is highly durable, mainly due to

the "skin" that forms during firing. This makes it

especially invulnerable to weathering. However, if cleaning

is necessary it needs to be done sensitively. One terracotta

rich building in Birmingham, which shall remain nameless,

had the outer "skin" removed in aggressive cleaning; the

result being that water has already seeped into the material

causing it to start to flake. |

| 3. |

This

staircase is not meant for two way traffic or someone

descending with their nose in a book, as one of the authors

found to their cost. |

| 4. |

Express & Star, Thursday 29th May, 1884. |

| 5. |

There

was in St Peter’s a life-size statue of John the Baptist

sculpted by the eminent artist Thomas Earp. Although still

in the church it is no longer on view. |

|

6. |

Phil

Drabble, "Staffordshire", Robert Hale, 1948, p.23.

Drabble goes

on to say “But Yankee pacers move like that, and I once

saw a photograph of a horse in a procession in an exactly

similar attitude”.

The legend of Thorneycroft’s suicide is a juicy one but,

like most legends, has little relationship to fact.

He did not in fact die until 1885. |

|

7. |

Sister

Dora occupied a similar favoured position in Walsall. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Stained Glass |

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to

Churches and Religious Buildings |

|