|

Churches and Religious Buildings. 1 - The Anglicans

The huge numbers of churches built during the reign of Queen

Victoria, and the subsequent demolition of many of them, would

appear to point to a rise and fall in religious observation.

Church going was a social convention, whilst the poor may have

been castigated for non-attendance, the middle-classes made a

social virtue out of religious observances and the upper classes

did what they had always done and pleased themselves.

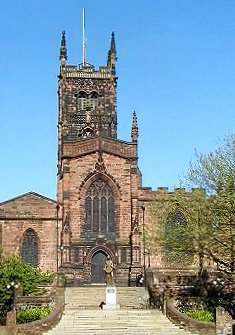

Wolverhampton contains many churches built by a wide variety of

denominations and though some may have fallen prey to demolition

due to dwindling congregations or the pressing need for space,

many still remain to delight and instruct. Still dominating the

town, despite recent developments is the Collegiate Church of

St. Peter. This church may at first appear to be a strange

inclusion in a book on Victorian Wolverhampton, for it is after

all one of the finest late medieval wool churches in the

country.1 However there was a major

restoration programme carried out between 1852 and 1865 by the

architect Ewan Christian, which not only involved restoration,

but the complete reconstruction of the choir. Although the

chancel and apse are in the style of the 13th century, they are

in fact by Christian, so it is valid therefore to include the

building in our study.

|

|

St. Peter's Church. |

Much has been said of Victorian church restoration both for and

against. For everyone (like one of the authors) whose heart

sinks when the words “restored by George Gilbert Scott” appear

in a guide book, there is someone ready to defend the

restoration programme on the grounds that the Victorians

preserved many buildings that would otherwise have been lost.

What were the restorer’s motives? They certainly felt that it

was their duty to restore churches and it has to be said that

they were the first generation capable of carrying out such a

task, for they were the first architects who fully understood

the constructional principles of medieval architecture. |

|

The Oxford Movement and Tractarianism, coupled with new ideas

about Gothic architecture, led many Victorian churchmen, both

Anglican and Catholic, to re-assess their ideas about worship.

The Eucharist was emphasized both as a great mystery and as

something in which the whole congregation should take part. So

altars had to be as far away as possible from the congregation,

but raised so that the priest’s actions were clearly visible.

In this new architectural and theological climate elongated

chancels, which separated the altar from the congregation and

contained the choir stalls for re-discovered sacred music, were

the ideal.

Medieval churches had many of these features, and were the

pattern for the new churches built in the 19th century. However

as well as renovating their fabric, the restorers could not

resist tinkering with the layout. Thus genuine medieval chancels

were often pulled down, so that churches could be restored

according to a spurious Gothic “ideal”.

Prime movers in the Anglican church “restoration” were the

Camden Society and the Ecclesiastical Commission, both motivated

by Tractarian ideals.

The question of Victorian restoration of our churches is

therefore a controversial subject. There is no doubt that much

restoration was insensitive, arrogant and did in fact attract

the criticism of contemporaries; so much so that the Society for

the Protection of Ancient Buildings was formed by William Morris

when he heard with horror of the proposed restoration of

Tewkesbury Abbey by the ubiquitous George Gilbert Scott. The

influence of the Arts and Crafts Movement led people to admire

buildings for what they were; often untidy, worn and not all of

a uniform style. These new perceptions of repair and

preservation, rather than wholesale restoration gradually gained

influence. In Wolverhampton, there can be little doubt that the

restoration of St. Peter’s was carried out with sensitivity by

Christian.2

|

|

Ewan Christian (1814-1895) set up business in 1842 and built his

first church, Hildenborough, near Tonbridge. In 1847 he restored

Scarborough parish church and in 1850 began the restoration of

St. Peter's. Christian belonged to the evangelical wing of the

Church of England and was architect to the Ecclesiastical

Commissioners from 1850 and consulting architect to the Charity

Commissioners from 1887. He was also President of the R.I.B.A.

One of his contemporaries said that his churches were

“distinguished more for quietness of repose than for

architectural effect”3

Christian found St. Peter’s in a very poor state, especially the

exterior: -“anomalous

features have been introduced; unsightly chimneys have been

erected; windows have been deprived of their mullions; and, in

fact, the whole exterior has been allowed to arrive at such a

state of decay and misery, that nothing but vigorous and well

directed efforts can possibly restore it to anything like its

former beauty”4

|

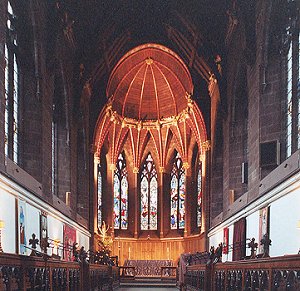

Looking from St. Peter's Nave towards the

Lady Chapel. |

|

Christian drew up a detailed report in which he described St.

Peter’s and also made his recommendations for repair and

restoration “upon a large and comprehensive scale”. The cost of

restoration was met by contributions of £2,000 from

Wolverhampton Council, £3,000 from the Ecclesiastical

Commissioners and a public subscription. By 1866 work on the

fabric of the building (excluding decorations) had cost

£11,875.14s 5d. It was carried out by the local firm of

Highways.

One of the main problems for the church was the fact that the

ground around the building had risen by about five feet. Hence a

serious problem occurred, as there was no means for carrying off

rain water.

The part of the church which has the stamp most strikingly of

the 19th century is the chancel, which was completely re-built

by Christian. In regard to the then existing chancel, Christian

wrote: -

“In the foregoing remarks no mention has been made of the

chancel, because hardly a fragment remains to show what it once

was. The existing building, erected in the seventeenth century,

is wholly unworthy of the noble church of which it should form a

part. The original chancel was certainly as much as four feet

wider, was probably lofty enough to harmonize in external

outline with the nave, and in that case must have been a very

important feature of the whole structure”..5

|

|

Christian's magnificently restored Chancel. |

The chancel as it stood looked a strange affair.

“The chancel was re-built about the year 1682, in a very plain

manner, the few mouldings with which it is enriched being in the

Italianate style. A few years ago the windows having become

dilapidated, new ones in the Norman style were introduced, and

the vacancy between the old and the new work, thus inserted, has

never been made good. The whole building is of most congruous

character, and can only be made to harmonize with the church, by

being re-built in proper form”.6

|

|

The re-built chancel is one of the most impressive parts of the

church. In 1872 as part of the restoration, the chancel walls

were painted with frescoes of Biblical scenes by a Mr. Parkes,

recommended by Christian as having “a remarkably good eye

both for harmony of colour and drawing”. The frescoes

were paid for by subscription from the congregation. In 1887

they were restored by the firm of Heaton, Butler and Bayonne,

better known as stained glass manufacturers. Presumably the two

figures on the west wall of the chancel, showing Moses and

Elijah are all that remain.

Christian was very much struck by the beauty of St Peter’s, but

realised there were barriers to a complete appreciation of its

proportions. Any visitor to an Italian church will immediately

be struck by the enhanced architectural effect occasioned by

there not being any seats in the body of the church. Christian

thought that the galleries and pews were a distraction from the

finer points of St Peter’s and wrote so in a letter to the Rev

J.H. Isles on the 12th

December, 1873.

“..but as regards the remainder of the church is it necessary to

put any pews? I was very much struck on my last visit with the

remarkable beauty of the interior of the church cleared as it

was of the obstructing galleries, and I could not help wishing

that you could clear out all other obstructions, so as to allow

the noble pillars to be seen in their full proportions. I think

if you could persuade your parishioners to have the whole of the

pewing removed and the area seated with chairs they would, when

once they had seen it clear, never wish to have their church

again cumbered up. At any rate it would be worth a trial so far

you will not again return to the old system…”7

|

|

The main restoration work of Christian concerned the re-building

of the west front which was considered at the time to be the

high point of the restoration. The nave clerestory was also

built and a new roof erected. Repairs were also carried out to

the porch and due to their unsafe condition; new parapets and

pinnacles were added to the tower.

|

St. Peter's Nave. |

|

“To ensure the execution of the work in a perfect and endurable

manner, I should recommend, that the greatest care should be

exercised in the selection of the stone, that the whole quantity

required should be quarried as soon as possible, none being put

into the building which had not been properly tested; that the

workmen should be carefully

selected, and that a limited number should only be employed

upon the work, under competent and careful supervision. I think

that if such a plan be adopted, and if the work be carried out

in the right spirit, and in a thoroughly complete and

satisfactory manner, funds cannot, and will not be allowed to be

wanting, for the most perfect restoration possible of this noble

edifice, the chief and most valuable ornament of the town of

Wolverhampton”.8

There are other features in the church that owe their

inspiration to Christian, most notably the Gothic memorial

arcading that runs beneath the windows of the south aisle. It is

made up of arches with tracery and pillars, each to contain a

brass memorial. Cost was, as ever, a problem. G.A. Purdey,

Christian’s assistant, suggests, Nov 26th 1877,

“could you not get the whole range done and charge the cost of

each one to persons wishing to put up a memorial tablet?”9 |

|

St. Peter's Church from the west. |

This advice appears to have been acted upon because each has a

dedication. There are many monuments in the church to 19th

century figures from the town. In the north transept is a plaque

to Thomas Thornley, one of the two M.Ps for Wolverhampton, after

its enfranchisement in 1832. Like many M.Ps who represented

industrial towns, he was an advocate of the repeal of the Corn

Laws. These laws, introduced in 1815, were designed to keep the

price of corn stable by regulating the flow of cheap corn into

England. It was also meant to give farmers a constant and fair

price for their corn. To many working people and their

representatives, it appeared that the price of corn was being

kept artificially high to maintain farmer’s profits. In 1846,

after much pressure from the Anti-Corn Law League and the

consequences of the great famine in Ireland, the Corn Laws were

repealed by Robert Peel. |

|

At this point we could perhaps mention one Victorian decorative

feature that is often neglected in guide books; that of tiles.

We shall meet them again not only in other Wolverhampton

churches, but in secular buildings, such as the Town Hall.

To many people Victorian church tiles represent all that they

dislike about that age; they were mass produced and have factory

uniformity that some find offensive. However, at the height of

the Gothic Revival there was an enormous demand for decorative

tiles. Pugin was an ardent enthusiast, who believed that the

tiles should be placed “near to the head of those church

ornaments which, next to stained glass, and when used in a

whole-hearted way, most charm the eye”. The type of tiles

that Pugin was advocating were encaustic tiles, the process of

whose manufacture had recently been rediscovered. Inlaid tiles

had been a feature of medieval churches but the manufacturing

process had been lost, especially after the Dissolution of the

Monasteries and during the Commonwealth.10

The process whereby they are made appears deceptively simple,

but the technique was in fact very problematic. Plastic clay was

pushed into a mould which had a raised pattern on the bottom.

The tile was then left to dry and afterwards a liquid (or slip)

clay of a different colour was poured into the hollows of the

design. After drying, the surface was smoothed with a knife. The

technical problem was to find two different coloured clays that

had similar contraction rate; otherwise the second clay would

pull away from the first. The name most associated with the

production of these tiles is Minton. Later patents, such as the

dust pressing method, which made the production of tiles faster

and more efficient, allowed them to be used in a wide variety of

buildings. These tiles were not only used for floors and walls,

but also as memorial tablets and examples of these can be seen

at the rear of the north aisle in St. Peter’s.

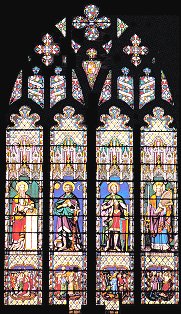

One of the glories of St. Peter’s is the range and fineness of

its stained glass. Of Particular importance are the windows by

one of the greatest stained glass designers of the 19th century,

Charles Eamer Kempe. Three windows by Kempe are situated in the

south aisle. Kempe was one of the most prolific of 19th century

glass designers. What first catches the eye is the paleness and

clarity of his glass, achieved by the use of large areas of

silver and white. His figures are often golden haired, with

golden haloes and richly draped robes of blue, red or green.

They are dressed in medieval style, though the windows have

nothing else in common with dark “Gothic” glass. Windows

frequently show single figures, angels, saints or prophets, each

standing beneath an elaborate canopy. The windows in

Wolverhampton are classic examples of their type. On occasion

however, a full scale scene is composed by dividing a large

window into a number of “lights” with one or two figures in

each.11 Many Kempe windows also contain his

signature, a golden Wheatsheaf taken from his coat of arms (the

reaper’s art of making sheaves is known as “kemping”). Many of

the windows made after 1895 are signed thus.

The three South Aisle windows summarize the history of Christian

evangelism. Moving from West to East, the first window

(installed 1891) shows prophets who foretold the coming of

Jesus. We have Enoch and Malachi from the Old Testament, to

illustrate the Christian belief that the Jewish prophets

foretold the coming of Jesus at his presentation in the

Jerusalem Temple. The second (installed 1895) shows the four

evangelists who wrote down the story of Jesus. The Evangelists

are shown with their traditional symbols: Matthew a Man, Mark a

Lion, Luke an Ox and John an Eagle.

The third window (installed 1890) shows early Christian

missionaries who spread the Christian message.12

Here we see:

St.

Ambrose, a 4th century Bishop of Milan, with his crosier in his

right hand. Ambrose encouraged the development of monasticism

and advised several Roman Emperors about Christianity.

St. Gregory the Great, Pope AD 590-604, carries a papal crosier

with a double cross. Gregory was responsible for sending St.

Augustine to convert the English to Christianity after seeing

some fair haired children in the slave market. Asking from where

they came he was told that they were Angles. “Not Angles, he

replied, Angels”.

St. Jerome, translated the Hebrew Old Testament and Greek New

Testament into a standard Latin text. He is shown holding his

Bible. The dog-like lion is often shown with Jerome for the

saint lived many years in a cave and the lion is believed to

have been a fellow occupant.

|

|

St. Augustine of Canterbury built a church at Canterbury on the

site of which the present cathedral stands. He is usually

considered to be the first Archbishop of Canterbury, hence his

crosier. The heart of fire which he carries is meant to

symbolise his burning desire to bring Christianity to England.

When the final window of the group was installed, the Express

and Star commented “..they are very artistic and beautiful

specimens of their art”

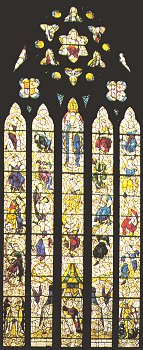

The Jesse window in the Lady Chapel, made in 1919, is a fine

example of Kempe’s influence on stained glass design long after

his death. The maker is unknown, but it is very much an

imitation of Kempe’s style, especially in its use of pale

colours and a medieval setting. Jesse, father of David, is shown

asleep in his tent or pavilion, the flaps held open by angels.

He dreams of his descendents, who fill the air above him, with

David over his head and Mary and Jesus top centre. Jesse windows

were a popular way of showing Jesus’ supposed descent from King

David in pictorial form.

|

The Jesse Window. |

|

The West Window. |

The West Window is in memory of the Duke of Wellington, who died

in 1852. Wellington was a tremendously popular figure, both for

his victories against Napoleon and his later political career;

(it may be difficult for us to understand why, since he was a

high Tory who opposed all reform and showed little political

acumen). A pamphlet describing the window in 1855 says:

“The window was designed by Mr. Wailles of Newcastle upon Tyne,

and will contribute much to maintain him in that pre-eminence in

this peculiar line of art for which he has long been

distinguished”.

The windows show four Biblical figures, depicted in the medieval

style beloved of the Gothic Revival. Each stands beneath his own

canopy, with a scene from his life beneath. They are Moses,

Joshua, Gideon and King David, warriors and legislators to show

the respect in which Wellington was held as a soldier and

politician. The pamphlet remarks that their applicability “to

the life and character of the noble Duke are evident”.

|

|

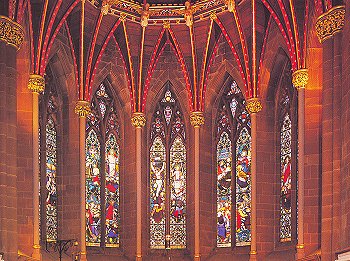

The apse windows were installed in 1867 and are therefore

practically contemporary with Ewan Christian’s restoration of

St. Peter’s. Their maker is not recorded.

One

wonders what Archdeacon Hodson would have thought of them. In

1852 he addressed the clergy of St. Peter’s on the matter of

church improvement in which he hoped the church “were not made

too dark”. |

The Apse windows at the eastern end of the

Chancel. |

|

Much as he admired “painted windows of a proper character and

the dim religious light which was thrown into our old

ecclesiastical structure” by which their jewel colours, he felt

that it should be borne in mind that the congregation “required

all the light which could be obtained to enable them to read

their prayer books and Bibles”.13

Of course, churches were unlit, except occasionally by gaslight

and the archdeacon was reflecting a widely held opinion.

The windows were painted with blackout material during World War

Two and its removal badly damaged the glass. They were repaired

after the war by Green of London. They tell the story of the

life of Jesus from his birth to the Crucifixion and his

Ascension into Heaven. On the North side is another

representation of the Four Evangelists (very different from

Kempe’s version in the South Aisle and a good illustration of

the diversity of 19th century glass design) and on the South

side the four epistle writers of the New Testament are shown.

To the left of the vestry is a window dated 1875, influenced by

the Aesthetic style which grew in popularity during that decade.

It is worth comparing the typical Aesthetic motifs of

intertwined branches and fruit which surround the figures with

the Gothic architectural canopies of the Kempe windows opposite.

The window is divided into three lights. The centre light shows

Jesus blessing the children, a poplar theme with Victorian

designers. On the left, illustrating “Blessed are the

Peacemakers” we see David’s friend Jonathan making peace between

David and King Saul. On the right, illustrating “Blessed are the

Merciful” we see the Good Samaritan.

|

The three windows in the north transept,

now the War Memorial Chapel. |

In the north transept we are confronted with a mystery: the

bottom section of a window of otherwise glass contains three

medallions showing Jesus healing Jairus’ daughter, Jesus

blessing the children and the Good Shepherd. Beneath the

medallions the blue glass tops of three further medallions can

be seen. |

|

This would appear to be the window referred to in Steen and

Blackett’s 1871 Wolverhampton Guide.

“There is a window in the North Transept still incomplete

which we may introduce to the reader on account of its

interesting character…It is composed of small circular panels,

which it is proposed to fill up after time, to the memory of

children…there are now three of the panels filled

with memories of little ones”.

It would seem that no more Wolverhampton children have been

commemorated since 1871!

St. Peter’s contains much more fine glass, but it is outside the

scope of this book, dating as it does from the First and Second

World Wars. In the chancel there are some fragments of Flemish

glass, which was frequently imported to “improve” English

churches in the late and early 19 centuries when English glass

painting was in the doldrums.

As

an expanding town in the mid 19th century, many new Anglican

churches were built to cater for the needs of the growing middle

classes and also in an attempt to gain adherents at the expense

of the Nonconformists. (A sign of respectability amongst many

wealthy Nonconformists was to abandon the chapel and join the

established church. Some, however, like the Congregationalist

Manders, remained steadfastly Nonconformist). Many of

these churches have now gone and it has to be said that not all

of them were of the highest architectural standards.

Christchurch was formed into a separate parish on October 27th,

1876 and a parish church, a plain building of stone in the Early

English style, was erected in Waterloo Road in 1861 / 1877.

According to Kelly’s Directory of 1896, the architect was T.H.

Fleeming, but according to Pevsner, it was Edward Banks. |

|

In Chapel Ash stands the church of St. Mark. The building itself

is not of great interest, but there are two points about the

church which will bear mention. Firstly there is its situation

at the bottom of Darlington Street. Seen from Queen Square down,

the church forms quite an impressive backdrop to the downward

sweep of the street. The other noteworthy feature of the church

is that it is a Commissioners’ Church. It is one of two in the

town, the other one being St Georges. Commissioners’ churches

were built under the Church Building Act of 1818 that provided

one million pounds for new churches in the expanding towns. |

St. Mark's Church, Chapel Ash. |

|

It appears odd to us that in the years following the end of the

Napoleonic Wars, when poverty and distress in England reached

dreadful proportions, the government should have sought to

ameliorate the situation by building churches to promote the

established religion; but this it did. Most of the early

examples, like St. George’s, were classical in style, the latter

were mostly Gothic. Although Gothic style was favoured, the

ground plan of the latter churches tended to be classical with a

large galleried preaching space with short chancel attached. The

church of St. Mark, which was built in 1848-9, is by C.W. Orford

and cost £4,850. Although, as stated earlier, we find the view

of the church quite impressive, it was not received so at the

time:

“In the choice of this site, an error perhaps has been

committed. A better spot in nearly every respect would have been

that upon which the parochial schools are erected. In as much as

it would have afforded easy access from Darlington Street and

Salop Street and the tower entrance would have obtained that

prominence to the Tettenhall Road which it now in greater

measure loses by being placed on the side of the thoroughfare”.14

At the time of writing, the future of the church of St. Mark’s

appears to be in some doubt, but it is undergoing extensive

restoration. The Parish of St. Mark’s was evidently a wealthy

one, for in 1875 a new vicarage was erected at a cost of £2,000;

exclusive of the site. Money was by voluntary contributions from

parishioners and their friends. It was evidently a fine house

and worthy of its parish, for it was built in red brick with

Bath stone dressing. The work was carried out by Mr. H. Lovatt

under the superintendence of the Wolverhampton architect Mr.

Veall.

We cannot leave our survey of 19th century Anglican churches

without looking at one of the finest examples in the area. To

find it we must leave the artificial constraints of the Ring

Road and go to Heath Town and visit the parish church of Holy

Trinity in Church Road. Until recently its graceful and grubby

spire could be seen over trees, when viewed from the Wednesfield

Road. The church has now been cleaned and the revelation of the

pink tinged sandstone under the grime came as a great and

welcome surprise. The architect was once again Edward Banks who

here surpassed himself.

Once again the builders were Highways. The foundation stone of

the church was laid in 1850. A contemporary account of the

ceremony states that:

“The new church is intended to be built in the Decorated English

style. It will comprise in its plan a nave and side aisles 85 by

55 feet and a chancel 36 by 19 feet. There will be a tower and a

spire at the south-west angle of the nave of a total height of

150 feet. It will be entirely built of stone”15

A visitor to the church today will see at once the accuracy of

this description. Above the south porch is a carving

representing the Trinity; a shamrock overlaid with a triangle.

Inside, the church is a delight. It is rather dark, due to the

latter addition of heavily-coloured stained glass, but the whole

building is beautifully proportioned. In the nave slender

columns divided into six bays support the five double clerestory

windows. The chancel is notable for the stone angel corbels

surmounted by slender columns with much carved foliage on the

capitals and a painted roof with more symbols of the Trinity.

Two royal heads on either side of the chancel arch are

unfortunately cut in two by the later addition of a screen.

The

stained glass, although of excellent quality, does make the

church rather dark. All the windows, except the Gothic East

Window of 1881, belong to the early years of the 20th Century.

However, there are two windows which deserve special mention.

The first is the West Window, installed in the 1930s. It is

unusual to find a Gothic window like this being made almost a

hundred years after the Gothic heyday, but what makes the window

remarkable is that it is very similar in style to the (genuine

Gothic) West Window of the other Banks’ church, St. Mary at

Bushbury, which also shows the Four Evangelists. By accident or

design? The second special window is in the chancel, the second

from the East on the South side. Dated 1922 it shows the angel

announcing Jesus’ birth to the shepherds. The window is in the

style of Morris and Company, and although it is much too late to

be the work of great masters Burne Jones and Morris, who died in

the 1890s, it closely resembles the style of Morris and Company

glass from the time of J. H. Dearle, Morris’s foreman who took

over the day-to-day running of the firm after Morris’s death. If

this is so, the church is privileged to have Wolverhampton’s

only example of Morris and Company glass.

Notes:

| 1. |

Wool churches are so-called because wool

merchants built them on the proceeds of their trade. Before

becoming an industrial centre, Wolverhampton was well known

as a wool market as the names Farmers Fold, Blossom Fold,

Mitre Fold etc. show. |

| 2. |

The restoration carried out by Christian was

not the first in the 19th century. Both Ebbels, the restorer

of All Saints, Trysull and Beck had had a hand in the

matter, but their restoration was mainly of the interior.

Although their restoration was praised at the time, it was

fairly cosmetic and the main problem of the building

remained un-addressed. There is no doubt that Christian was

greatly impressed by St. Peter's and concerned that his

restoration should be carried out competently. |

| 3. |

Annonymous, "Ewan Christian", 1896, p.21. |

| 4. |

Letter from Ewan Christian, "Report on the

Collegiate Church of St. Peter, 1852. |

| 5. |

ibid |

| 6. |

ibid |

| 7. |

Letter from Ewan Christian to Rev. J.H.

Iles, May 16th 1872. S.C.R.O. |

| 8. |

ibid |

| 9. |

Letter from Purdey (Christian's assistant)

to Rev. Iles, Nov 26th 1877. S.C.R.O. |

| 10. |

To see some genuine encaustic tiles in situ one only needs

to go as far as Buildwas Abbey where they are laid in the

chapter house. |

| 11. |

A good example can be seen in the South Transept of

Lichfield Cathedral. Excellent examples of Kempe's work can

also be seen in Wightwick Manor, where he stayed on several

occasions between 1886 and 1899. The house contains Kempe

windows and also a painted chimney piece and a frieze

telling the story of Orpheus and Euridice. |

| 12. |

The window is a memorial to Rev. Iles, who

was instrumental in the restoration of St. Peter's. |

| 13. |

Wolverhampton Chronicle, Wednesday 26th May,

1852. |

| 14. |

Wolverhampton Chronicle. 1849. |

| 15. |

Rev G. Corbett (ed), "One Hundred Years of

Heath Gown". |

|

|

|

|

| Return to

Civic and Public Buildings |

Return to

the contents |

Proceed to

Churches and Religious Buildings 2 |

|