|

MRS O. F. WALTON'S ACCOUNT OF DAISY BANK

Mrs. Walton's "The Lost Clue" was published, by

the Religious Tract Society, in 1907. So the account of Daisy

Bank which it contains was probably based on experience of the area

at the turn of the century. Up to the time she moved to

Wolverhampton, there was nothing in Mrs. Walton's life which

suggests that she would have had any experience of this sort of

industrialised area; and it may therefore be that her description of

the area is more dark and drastic than the reality justified.

But there must be substantial truth in it.

Part of the cover of The Lost

Clue.

Our heroine,

Marjorie Douglas, lives in the Lake District, in Borrowdale.

As the result of the sort of financial misfortune that was common to

Victorian heroines, she needs to find a job. Seeing an advert

for a mother’s help in Daisy Bank, Staffordshire, and thinking that

the place sounded very pleasant, Marjorie applies for the job, gets

it and travels to Daisy Bank by train, changing stations at

Wolverhampton. When she arrives at Daisy Bank station, late in

the evening, she is met by the twelve year old daughter of the

Holtby household, Patty:

|

“Are

you Miss Douglas?”

“Yes, I am. Have you come to meet me?”

“Yes. You're to leave your box at the station, and

father will send for it.”

“Can't I get a cab?”

The girl laughed. “Cab!” she said. “I should think not !

We've no cabs here.”

|

The site of the

railway cutting and Daisy Bank station

to-day. This part is now a linear park

but the rest of the cutting has been filled

in. |

They

left the box in the care of the porter, and the girl led

the way to a steep flight of stone steps leading to the

road above. Then she went along a roughly made cinder

path, and Marjorie followed a little behind, at times

plunging into great pools of water which she could not

see in the dim light, and at other times almost falling

on the slippery mud. Then they turned into a short

street, if street it could be called. It was so

irregular that it seemed to Marjorie as if houses of all

kinds had been thrown down there, and left to find their

own level and own position. They passed one or two

squalid shops, which appeared to sell little besides

shrivelled oranges and the commonest of cheap sweets.

| Part of the

cutting, south of the Great Western pub, now

filled in. |

|

As

they walked on together the street lamps became fewer,

with long stretches of darkness between them, and at

length the furnace lights formed the only illumination,

and these every here and there revealed a scene of utter

desolation.

“What a curious place!” Marjorie said to the girl at her

side.

“I should just think it is,” she answered. “I hate it,

and mother does too!”

“Why do you live here, then?”

“Oh ! Father is the manager at the works over there. We

have to live here, I suppose; it's a hateful place!”

“Where are we going now?” asked Marjorie, as they seemed

to be leaving the road and turning into the darkness.

“Oh, it's a short cut over the mounds. Take hold of my

arm; you can't see, and you'll be walking off into one

of the pit‑pools. The lakes we call them,” she added,

with a laugh. “You come from the Lakes, don't

you?”

“Yes, from such a lovely place.”

“Well, you won't like our lakes, I'm afraid. They're

only rainwater that lies in the hollows between the

mounds. There are plenty of them about here.'

“Isn't it better to keep to the road such a dark night

as this?”

“You can't,” said Patty, “it's all deep mud; you'd stick

fast if you tried.”

At

length they saw a light, which came from the windows of

a square stone house with a small garden in front of it,

and Patty took a latch‑key from her pocket and opened

the door. Immediately a rush was heard from an inner

room, and six children of various ages ran out to see

the newcomer. |

Our heroine immediately sets about her work of

putting the house and the household to rights. This takes her

a day or two. Then:

|

That

afternoon Mrs. Holtby insisted on Marjorie's going out

for an hour or two, that she might get some fresh air

after her hard work.

So

far Marjorie had seen practically nothing of Daisy Bank,

for it was too dark the night before for her to do more

than see the dim outline of what she passed, and from

the windows of Colwyn House there was merely a narrow

view, shut in by houses on either side. She had not

expected to see much to charm her during her walk, but

she was hardly prepared for the scene of utter

desolation that met her eyes as she went down the muddy

lane leading from the house.

On

one side of it were a few tumble‑down cottages, damp and

discoloured; on the other was an open waste, strewn with

the remains of old furnace heaps. She looked across this

wilderness to the huge pit‑mounds, rising in all

directions, the very picture of gloom and dreariness.

Finding that the lane was still impassable from the

depth of mud, she turned upon the waste common, parts of

which were covered with thin, smoke‑begrimed grass. Here

there stood two old houses, even more wretched and

forlorn than those she had already passed. The bedroom

window of one was partly blocked with wood, and the room

was given up to pigeons, which flew in and out at

pleasure. The door of the other house was open, and she

saw a cock and a hen and three fat ducks walking about

as if the whole place belonged to them.

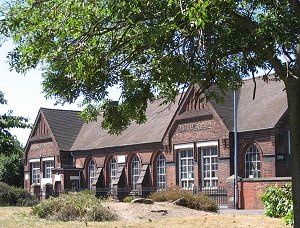

| The book contains

a brief reference to the fact that the

children go to school. Marjorie is

surprised that there is a school at all; but

she is told that there is an it is quite a

big one. This is Daisy Bank school,

still as it was in those times but now used

as a library and community centre. The

city council proposes to demolish it and

replace it with a modern version. |

|

Further on she came upon two ragged women, down on their

knees upon an old mound, raking over the muddy ashes,

and picking out the wet and dirty cinders which were to

be found amongst them, and then stowing them away in an

old sack.

“What are you doing?” Marjorie asked.

“Getting cinders for the fire.”

“Will they burn?” she asked in astonishment.

“Yes, with a little coal. It's better than no fire at

all.”

Marjorie walked on, sick at heart, as she thought of the

kind of homes that those women must have. The cold, icy

wind was blowing in her face, and she shivered as she

thought of the apology for a fire which would be kindled

with those lifeless cinders.

After this she passed more houses and more mounds; but

nowhere in the whole place did she see a vestige of

anything whatever that was pleasant to look upon, The

houses were destitute of paint, the doors and

window‑frames were bare and unsightly, the numberless

broken panes were filled in with rag or paper. More than

one of the houses was in ruins ‑ every window broken,

and the walls ready to fall in. The mines below had

caused these houses to sink; they had been pronounced

unsafe, and had been left deserted, but no one had taken

the trouble to clear away the ugly, dismal ruins. There

they stood, blackened with furnace smoke, unsightly and

melancholy objects.

|

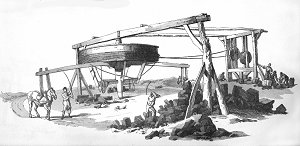

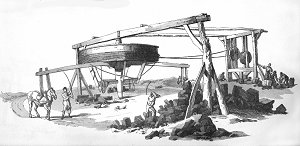

A

mine with a "heavy wooden frame and great

wheel"". Drawn in 1808 but used in the

Daisy Bank area and the rest of the Black

Country coal mining area until all mining

stopped. |

Only

two coal‑pits were working, so a man told her, who was

smoking a dirty clay pipe at his door. Some had stopped

because of bad trade; some were worked out; some had

filled with water, and were therefore abandoned. Yet at

the mouth of each of these deserted pits the heavy

wooden frame and great wheel still remained ‑ a gloomy

memento of more prosperous days. In every direction in

which she looked Marjorie saw unmistakable marks of

squalid, cheerless poverty; the only prosperous‑looking

building being the public house at the corner, which

appeared to do a thriving trade. The whole country was

honeycombed with mines, and, in consequence, many of the

houses had sunk below the level of the others in the

same row. Everything in Daisy Bank seemed crooked and

out of shape. Other cottages were scattered amongst the

furnace debris, were built anywhere and everywhere that

a place could be found for them, on different levels and

in sundry nooks and corners of the hilly waste.

| The Great Western

pub, originally the Great Western Hotel,

built on the main road near Daisy Bank

Station. Still a popular pub it serves

what is now an almost entirely residential

area, with few signs of the old industries

and their waste tips. |

|

Then

she came to higher mounds still, and crossing these she

saw deep, black pools in their hollows, stretches of

dark, stagnant water, which never reflected anything

that was pretty or bright except the moon in God's pure

heaven above. Here and there some one, more thrifty than

his neighbours, had made a little garden in the waste;

but what could grow in such a smoky atmosphere and in

such poor and barren soil? A few struggling plants of

the most hardy kinds were all that the best garden in

Daisy Bank could produce.

Marjorie was glad to get back even to the dismal house

in which her lot was cast; it seemed almost cheerful to

her after the unkempt hideousness of its depressing

surroundings. |

Somewhat later

Marjorie visits a poor and invalid old lady (for whom, of course,

she does good works, and who, therefore, turns out to hold "the lost

clue" which turns round the fortunes of Marjorie's boy friend and

thus of herself. Mrs. Walton, at this stage in her writing

career, does not hammer the point that this is God's reward for

Marjorie's Christian good works but the moral is clearly there).

A part of their first conversation tells us more about the Daisy

Bank area:

“What a large house

you have, Mrs. Hotchkiss!”

“Too large!” groaned the old woman; “it used to be a

farm”.

“A farm here!” exclaimed Marjorie.

“Yes, long ago, in the old time when they hadn’t found

coal; it was all country here then”. |

That is an accurate account. The field

pattern shown on old maps seems to indicate that farming continued

there long enough for the fields to have been enclosed.

There is one other passage about Daisy Bank -

which provides an interesting guess about the origin of the name.

| Daisy Bank did not

alter much with the changing seasons: there was very

little to mark the progression of spring, summer, and

autumn. Barely a tree was in sight, and the few that

were to be found were so stunted, blighted, and covered

with smoke that the spring freshness of their leaves

lasted but a few days. Upon the mounds grew a few coarse

daisies ‑ at least, the children called them daisies;

they were a kind of feverfew with a daisy‑like flower.

Nothing else would grow there, which is perhaps why the

place got its name, a name which had at first appeared

to Marjorie to be utterly unsuitable. |

There seems to

be no reason to doubt that Mrs. Walton has provided us with an

accurate enough picture of Daisy Bank at the end of the nineteenth

century. It is, perhaps, more true to life than the

story to which it is a backdrop. In the novel Marjorie’s life

crosses and re-crosses that of a Captain Fortescue, who, as a result

of the sort of financial misfortune that was common to Victorian

heroes, had become almost penniless. But by a series of

incredible coincidences he is restored to his rightful position and

marries Marjorie, who finds herself to be Lady Derwentwater and

incredibly rich - a very proper outcome for such a good and godly

girl.

|