|

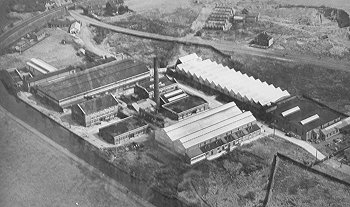

H.M. Factory, Heath

Town, later occupied by Mander Brothers |

| Background

By the late 19th century, many uses had been found for

phosphorus, including munitions, matchsticks,

fertilizers, and for the manufacture of saccharine. It

had originally been produced in retorts, heated in a

coal furnace, and later in a gas-fired furnace.

Production was labour-intensive, and relatively

expensive, but this all changed with the development of

a purpose-built, electrically-powered furnace, which

revolutionised production, and turned it into a

continuous process.

The first phosphorus factory using the new process

was built at Wednesfield in 1890 by the Electric

Construction Corporation, which later became the

Electric Construction Company (E.C.C.). In 1888 Dr.

Readman of Edinburgh took out a patent for producing

white phosphorus by the use of an electrically-powered

furnace. In 1890 the E.C.C. bought Readman's patent, and

Mr. Thomas Parker (E.C.C.'s Works Manager) and Mr. A. E.

Robinson, F.C.S. (E.E.C.'s chemist) began experimenting

with a revised process, and took out a patent for the

application of heat by an electric current through

phosphatic materials in a closed furnace. The new

process worked extremely well, and resulted in the

formation of The Phosphorus Company, and the building of

a new purpose-built factory at Wednesfield by the side

of the Birmingham canal, near to the railway station.

The process operated on a small scale using several

electric furnaces, which were driven by a

triple-expansion marine steam engine, delivering 700

horse power. Steam was fed from three Babcock and

Wilcock’s boilers, which were fed with heated water to

reduce the cost of producing steam. The engine drove an

alternator that was 8ft in diameter and produced 400

units of electricity from a single phase supply.

Intense heat for the furnaces was produced by powerful

carbon arcs, a technique invented by Thomas Parker to

create a small and compact design.

The furnaces, built of firebricks inside a framework

of cast iron plates, with a capacity of six cubic feet,

were 8ft. square and fitted with a hopper at the top

that allowed phosphates and coke to be poured-in without

any heat vapour escaping. They were air-tight, so that

no smoke was generated, and the whole of the

ingredients, except for a little slag, produced the

phosphorus.

|

|

A cross-section of one of the

furnaces. |

The resulting liquid was drawn from the

furnace using a tapping principle, similar to that used

in a blast furnace, then passed through pipes and

condensers to form a deposit of extremely pure

phosphorus. It required a minimal amount of refining

before being formed into circular cakes. The charge for the furnace was carried in buckets and

tipped into the hopper at the top. It consisted of coke

and an already calcined mixture of Redonda stone and

tar. The horizontal carbon electrodes were 12" square

and received 80KW through iron connection forks.

They

were tamped everywhere with carbon strip, ground coke

and pitch.

Care had to be taken to ensure that there was always

enough material between the carbons to maintain

electrical contact. |

A circular furnace was also built which performed better

and was more reliable. The firebrick hearth was replaced

by a gas carbon retort strip. The hopper was moved to

one side to make way for a vertical electrode. This became the standard

design and remained unchanged for some time.

The production costs were far less than with any other

system, and the process was so successful that after

several month’s production, plans were made to enlarge

the works. The patents and the factory were acquired by

the Phosphorus Company Limited. It was hoped that

they would be able to produce 1,000 tons a year, which

amounted to half the world’s production. The phosphorus

furnace became known as "The Wednesfield Furnace" and

appeared in many school textbooks. The new process was

inherently safer than the old process in which

phosphorus was distilled in earthenware retorts, which

were dangerous to handle because of a fire hazard. The

phosphorus was transported from the factory in 50lb. blocks

which were placed in a tank of water. |

The later type of furnace. |

|

Another view of the later,

circular furnace. |

The patents and the buildings were later sold to Albright and

Wilson of Oldbury for £16,000. Certain conditions were

applied to the sale including a guaranteed consumption

of not more than 8 units of electricity for every pound

of phosphorus produced, and a minimum yield of 75 per

cent. At that time the measurement of electric current was in

its infancy and so it was difficult to verify the

consumption of the furnaces. Sir Alexander Kennedy, an

eminent engineer, was appointed as assessor.

He

brought-in the greatest electrical engineer of the day,

Lord Kelvin, who had developed the most accurate instrument at the time

for measuring electric current, the Kelvin balance. Lord Kelvin applied his apparatus to the task in

hand and proved that the consumption was within the

specified limit. The sale conditions were duly met and the sale

went ahead. |

The condensers developed at Wednesfield.

The Wednesfield factory continued in operation

for a further two years until a new factory, along the

same lines, was built at Oldbury, which opened in 1893.

After transferring production to Oldbury, the Wednesfield factory

was gradually shut down, and soon closed.

|

| The H.M. Factory at

Heath Town The closure of the Wednesfield

factory was not the end of phosphorus production in the

area. In Oldbury, Albright and Wilson Limited had gone

from strength to strength using improved versions of the

Wednesfield furnace. In the early years of the First

World War the company developed a range of munitions for

the army including phosphorus-filled shells, hand and

rifle grenades, and 'Chinese tumblers', and 'plum

puddings' for trench warfare. On detonation they

liberated phosphorus which produced phosphorus pentoxide,

a non-poisonous gas that acted as an extremely efficient

smoke screen to mask the enemy's fire. The army

initially thought that phosphorus-based munitions were

far too dangerous for troops to handle, and so little

interest was shown. After much persuasion the devices

were accepted, and in a short space of time large

numbers were being produced. The other armed services

also used phosphorus devices. The Royal Navy and

Mercantile Marine frequently used phosphorus smoke

screens, and the Royal Flying Corps used wind-direction

indicators called candles, which continuously burned

phosphorus. They also used 'toffee' bombs which

contained a mixture of white phosphorus and amorphous

phosphorus against Zeppelins and kite balloons.

Phosphorus for smoke screens was needed in large

quantities, which Albright and Wilson Limited could not

hope to manufacture. The furnaces were already working

beyond their safe limits producing large amounts of

phosphorus for shells. To overcome the supply problem

the Trench Warfare Supply Department under Sir Alexander

Roger, decided, with Government assistance, to build a

new factory for the production of phosphorus on a six

and a half acre site at Heath Town, which had been

purchased towards the end of 1915 from Lord Barnard.

Wilson Lovatt & Company of Wolverhampton were given the

contract to build the factory, and work got underway in

January 1916. Extra plots of land covering around six

acres were also purchased, mainly from the adjacent

London and North Western Railway. The factory had twelve

500kW, single electrode furnaces and condensers, with

wooden tops that were lifted by mechanical gear, and

filters in a separate building, similar to the ones in

use at Oldbury. There were also four resistance mud

furnaces, a fitting shop, carbon shop, electrician's

shop, a time office, and a bungalow for the foreman.

Power was purchased from the Wolverhampton Electricity

Department, and production got underway in May 1917.

During the first year of operation, a further twelve

furnaces and condensers were built, along with filters

and four more mud furnaces. A railway siding and mixing

house were added because the quantity of furnace mixture

required for the plant was too great for Oldbury to

supply. Initially it had been brought from Oldbury,

shovelled out of the boats and put on conveyors which

loaded the bins above the furnaces. The phosphorus was

moulded into 50lb. blocks which were put into open

tanks on wheels, and carried to the Oldbury works by

canal boat.

A plan of the phosphorus works.

|

1. |

The Offices. A single

storey building of brick and slate, consisting

of four offices with toilets. |

|

2. |

Furnace House 1.

Brick-built with a roof in two spans on steel

principals with a slate roof, and 7 blocks of

concrete tanks. |

|

3. |

Mixing House. Brick

walls, 3ft. thick at the base, and a Belfast

roof covered with ruberoid. |

|

4. |

Fitters' Shop. Brick

walls and Belfast roof, with 2 test rooms and a

toilet. |

|

5. |

Filter House. Brick

walls at the ends, open sides with brick piers,

and a ruberoid-covered Belfast roof. |

|

6. |

Bleacher House. Brick

walls at the ends, open sides with brick piers,

a ruberoid-covered Belfast roof, and concrete

tanks. |

|

7. |

Mud Furnaces. Brick

walls at the ends, open sides with brick piers,

a ruberoid-covered Belfast roof, concrete tanks,

and transformer houses. |

|

8. |

Boiler House. Bricked-in

boilers with a flue and chimney stack. |

|

9. |

Furnace House 2.

Brick-built with a roof in two spans on steel

principals with a slate roof, and 4 blocks of

concrete tanks. |

|

10. |

Transformer Houses.

Brick-built with a slate roof. |

|

11. |

Anthracite and Chip Stores.

Brick walls, a double-span Belfast roof, and

adjoining loading shed. |

|

12. |

Mixing House. Brick

walls, 3ft. thick at the base, and a Belfast

roof. |

|

13. |

Pump House. Brick walls,

a ruberoid-covered Belfast roof, and a well for

the pumps. |

|

14. |

Four Store

Tanks. 40ft. by 18ft. concrete tanks. One

never completed. |

|

15. |

Canal Loading Deck.

Covered span roof with open sides. |

|

16. |

Canteen and Kitchen.

Wood and galvanised iron structure, 3 rooms and

a toilet. |

|

17. |

Store. Wood and

galvanised iron structure with a lean-to, 2

stall stable. |

|

18. |

Bath House and Toilets.

Brick and slate built with a wash house,

dressing room, 4 bath rooms, and 6 toilets. |

|

19. |

Foreman's Bungalow.

Single story, brick and slate with an entrance

hall, two bedrooms, a sitting room, a combined

kitchen and scullery, a pantry, a coalplace, an

outside toilet and a paved yard. |

|

20. |

Concrete Gantry. 12ft.

wide. |

After the war had ended, and the orders for munitions

ceased, the factory was of no further use to Albright

and Wilson, and so in 1920 the plant was sold for £6,000

and scrapped. The land and buildings remained derelict

until the mid 1920s when the site was sold by order of

the Surplus Stores of the Liquidation Department of H.M.

Treasury. The site, along with some adjacent land was

acquired by Mander Brothers, for the building of a new

factory.

|

|

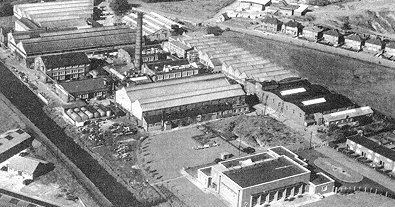

The new Heath Town factory in 1932. |

In the 1920s, Mander Brothers Limited was set up by

Charles Mander's son, Charles Tertius Mander Bart., his son Sir Charles Arthur

Mander, Bart., Gerald Poynton Mander, Sir Geoffrey Le Mesurier Mander

and Howard Vivian Mander. |

The new factory was soon built for the production of

Mander's paints and printing inks, and became a

large local employer, and a great success.

|

|

Read George Cox's memories of

the Heath Town Factory |

|

|

|

Left: A tin of Koreol motor

enamel. Right: A leaflet advertising Mander's Koreol

Varnish, "a practical alternative" to cellulose varnishes

(undated).

Manders also produced Manderlac cellulose

motor finishes which were quick drying and resistant to fading.

|

|

|

Charles Tertius Mander Bart.

Photograph courtesy of Jennings |

In 1927 Manders became paint and wallpaper merchants, when the

company acquired some 50 depots through the purchase of W. S. Low

Limited's long established distribution chain.

In 1937 the printing ink interests merged with John Kidd &

Company Limited to become one of the largest printing ink

manufacturers in the U.K.

In the same year the public company Manders (Holdings) Limited

was formed, gathering together in one major grouping, all the

specialised companies, now operating successfully at home and

abroad.

In 1945 the factory at Wednesfield Works was sold to Griffiths

Paints.

|

|

Left: A tin of Matsine, a

transparent flat drying colour which could be used as a wood

stain, a scumble, or a glaze. |

In 1961 the company produced

its 500,000th gallon of paint. The photograph shows the tin

being filled. |

| In the 1960s the company's original factory in Wolverhampton

town centre closed, and the site

was redeveloped into the Mander Centre, a shopping centre covering 5

acres. The company set up a property division to control the

project, in which retail and office properties were leased.

The Mander Centre opened on 6th March 1968 and contained 134

outlets.

It was designed by James A. Roberts who designed the Rotunda in

Birmingham. The new venture formed a secure base for the company's

future activities. |

An advert from the 1920s.

|

| In 1973 British Domolac Limited, an industrial paint

company, was purchased, and Manders' Industrial Paints Division added to it. The company then started to trade as Mander-Domolac

Limited. In the 1980s Manders acquired QC Colours and

Johnson and Bloy, and integrated them into the company by

forming a new division in 1989 called Manders Liquid Ink

Division. It was headed by Managing Director, John Mackenzie,

formerly of QC Colours. |

A photograph of the factory from a 1970's

advertisement. |

|

Heath Town Works in 1984. |

A new decorating centre was opened at Heath Town in 1990 and

the new headquarters of Mander-Deval Wallcoverings was built on

land adjacent to the factory. In 1992 an unsuccessful takeover bid from a rival

company, Kalon, led to Manders reviewing its long-term strategy.

The decision was taken to concentrate on the manufacture of

the highly

successful printing ink, and so during late 1993 and

early 1994, the decorative paints part of the business, and the Mander Centre, were sold. |

| The factory in July 1988 after

the completion of a new 450,000 cubic ft. tin store.

This was

part of a two million pound investment at the factory which saw

the installation of modern

production equipment, and improved storage facilities. |

|

|

The photograph shows staff

and volunteers at the Springburn Museum in Glasgow. The museum

acquired the North British built steam locomotive, Garratt 4112

after its withdrawal from service in South Africa.

The

locomotive needed repainting. This was made possible by

sponsorship from Manders, who supplied the paint.

Manders paints

were ideal for the purpose as Manders used to supply paint to

British Rail. |

An advert for Vernasca wall

paint. Courtesy of David Wilsdon. |

|

An advert for Aqualine water

paint. Courtesy of David Wilsdon. |

|

A 1958 advert. |

Manders also acquired a number of the world's

leading ink manufacturers, including a major competitor, Croda, with

operations in the U.K., Ireland. Italy, the Netherlands, New

Zealand, South Africa and the USA.

In 1994 the Netherlands based Premier Inks was acquired. It was

one of Europe's largest manufacturers of publishing inks.

In the same year Morrison Inks of New Zealand was also acquired to give

Manders a strong world-wide presence.

In 1996 Manders made its final acquisition with the purchase

of a large facility in Sweden which specialised in metal

decorating coatings. Six centres of excellence were set up in

various European locations, specialising in commercial sheet fed

inks, liquid inks, metal decorating inks, news inks and

publication inks.

|

|

| The company invested heavily in research and development

to ensure that its products kept ahead of the competition and satisfied

customer's needs. The Wolverhampton factory became the Centre of

Excellence for the manufacture of coldset inks, which are fast drying

inks for use in newspapers. Most of the national and provincial

newspapers used inks that were manufactured in Wolverhampton, and the

company also supplied many newspapers throughout Europe. Printing ink

sales increased from £40 million in 1993 to £160 million in 1997. About

60 countries were supplied through 28 manufacturing and distribution

centres. |

A tube of artist's oil colour in original

box. |

|

In 1998 Manders was acquired by the Flint Ink Corporation

of America. This is the largest privately-owned ink manufacturer in the

world. The Heath Town works became the European Headquarters of Flint

Ink Europe, and the remainder of the works closed. It has since become Manders Industrial Estate, which is now home to a variety of companies. |

|

|

Return to the Canals

and Industry Menu |

|