|

Churches and Religious Buildings. 2 - Non Conformism

Anyone

familiar with the position of Roman Catholics from the

Reformation onwards, will be aware that attitudes towards them

ranged from outright persecution, through suspicion to

indifference. Laws prevented Catholics from playing a full part

in public life and from entering the universities, or from

holding high office in the state.

After

the Protestant Reformation there were plots to put the Catholic

Mary of Scotland in place of the Protestant Elizabeth. Thus

began an association in the public mind of Catholicism with

treachery. The Gunpowder Plot, Rye House Plot and the Jacobite

rebellions all served to reinforce the association. To be a

Catholic was not in itself a crime but priests were hunted and

persecuted. Some families did cling to the old faith with a

notable example being the Giffards of Chillington Hall. The

immediate heirs to the throne could not marry a Catholic and

Catholics could not enter the universities, as they were not

eligible under the terms of the University Tests Act, a law that

was not repealed until 1872. The main impediment to public life

was that Catholics were not eligible to sit in the House of

Commons, as were not other non-conformists. As British public

life has a habit of throwing up paradoxes which, when resolved

inch us forward into the previous century it was but a short

time before the position of Catholics came to a head. It was in

the late 1820s that the issue was forced upon the government.

|

|

Giffard House in winter raiment. |

There is a

long history of Catholicism in Wolverhampton for the town was once

the seat of the Vicar Apostolic of the Midland District and it was

not until the restoration of the Catholic hierarchy in 1850, that

the administration was moved to Birmingham. Such was the importance

of Wolverhampton to Catholic England that it was once known as

“Little Rome”. One of the leading Catholic families was the

aforementioned Giffards and it was at Mrs. Elizabeth Giffard's house

in North Street that Wolverhampton’s Catholics heard mass. In 1727,

the Catholic population felt safe and well established enough to

build a new house and chapel on the site of an old one. |

| The new

house, the present Giffard House, was finished in 1730. There was

obviously a chapel in the house, in this case dedicated to S.S.

Peter and Paul. The chapel was greatly expanded after 1826 as a

memorial to Bishop Milner who was buried in the orchard at the rear

of the house. The body was exhumed and placed in a new tomb in 1874

before being moved to its present position in the crypt in 1930.

In the course of

expansion it became one of the first Roman Catholic churches to

be built in England since the Reformation, a fact of which the

congregation is justly proud. The church has recently undergone

extensive restoration. |

|

The

changes in law which had freed Roman Catholic churches from

appearing as private houses and the resurgence of enthusiasm for

the Catholic faith, led to a spate of Catholic churches being

built, especially after catholic Emancipation in 1929. In 1852,

the full church hierarchy was re-established although not

without a great deal of resistance from those who thought that

the Roman Catholic Church was once again seeking ascendancy in

England.

|

The interior of St. Peter and St. Paul. |

|

In an

age of increased industrialisation and mass production, many

people sought the spiritual values of the Catholic faith, as

they perceived them. Even those who were not converted, but

chose to remain within the established church, sought to raise

church architecture, decoration and layout to give added

spirituality to worship.1

One of

the finest Roman Catholic churches in the Wolverhampton is that

of St. Mary and St. John in Snowhill. (It was originally known

as St. Marie’s and St. John after the usage of the day). The

church of Saint Mary and Saint John by Charles Hansom (not to be

confused with his brother J.A. Hansom, the architect of

Birmingham Town hall and patentee of the cab that bears his

name) was built between 1851 and 1855 and cost initially

£10,000.

|

|

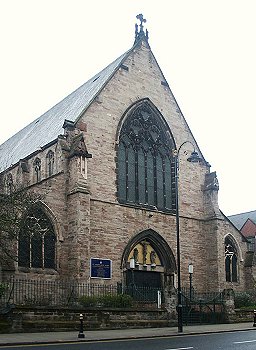

The church of

St. Mary and St. John. |

One of the

prime movers behind the building of the church was John Hawksford,

who later became Wolverhampton’s first Catholic Mayor. He purchased

from the Duke of Cleveland’s agent land adjoining Snowhill. The

purchase price was £2,000, a large sum but worth it as the site was

a valuable one. The Snowhill area already had an air of sanctity

about it, as there were Congregational and Unitarian chapels

virtually next door to each other to say nothing of Saint John’s.

The land purchased formed part of the Duke’s “Gardens” and Hawksford

undertook to fence the land off from them. Bishop Ullathorne laid

the foundation stone in 1851 and the work carried out by the

Wolverhampton builder, Wullen, whose name is remembered in Wullen

Street, Whitmore Reans. The construction of the church unfortunately

coincided with the Crimean War, which led to delays and increased

costs. Also, sadly, the stone used from a local quarry, unproved for

building, was used and the industrial atmosphere played havoc with

the fabric. |

|

The

febrile nature of the stone revealed itself in flaking masonry

and general decay. The church that Hansom proposed is much as we

see it today except that his plans called for a tower and spire

at the intersection of the nave. The entry point for the tower

can be seen just inside the Sacred Heart Chapel.

The

nave was opened on Tuesday 1st May and at the ceremony

Cardinal Wiseman preached a sermon so badly that most of it was

inaudible. After the opening, a “dejeuner” was held at the old

Corn Exchange. When opened, the entrance at west front was a

double doorway with a central stone pillar that has since been

removed. Inside the nave and aisles were much as they are today

except that the capitals and corbels had not yet been carved. At

the time of opening there was a solid wall behind the soaring

chancel arch.

The

same architect between 1879 and 1880 enlarged the east end. The

pillars in the nave were scraped to match the new stone of the

chancel and the three medallions containing angels were carved

at the base of the pulpit for the occasion. When the chancel was

opened it was in the presence of the aged Cardinal Newman and

Hansom the architect afterwards attended the luncheon.

As it

stands today, the entire length of the building is 150 feet, but

it is its width that is so noticeable, being 35 feet from centre

to centre pillar. However these facts convey nothing of the

interior design of the church, for it is quite simply a lovely

building. Elegant, calm and with a wealth of symbolism, the

apsidal chancel, which is vaulted unlike the nave, really does

soar and the dark blue paint, though now peeling, enhances the

noble effect. At the intersection of the nave and chancel,

decorated bosses carved in floral patterns cover the ribs. One

feature of the Gothic Revival style is the use of symbolism.

This in the church there are three lancet windows, three arches

on either side of the chancel, three windows in the apse each

with three lights, symbolising the Trinity. The whole plan is

cruciform. Above the arches there are clerestory windows with

depressed pointed arches. The side aisles are twenty feet high

and fifteen feet wide and are lit by pointed windows each with

three lancets.

|

| In the centre

of the chancel is a richly carved reredos, 12 feet by 18 feet, and

High Altar. There is a tabernacle surmounted by an open canopy about

20 feet high. At either side are two richly canopied niches

containing statues of the two patron saints, S.S. Mary and John. The

front of the high altar is carved with three panels in low relief,

two of them showing Abraham offering Isaac and the Thanksgiving of

Noah after the Flood; the central panel shows the crucifixion. The

altar was carved by Mr. Houlton (Boulton surely?) of Cheltenham, to

the design by one of the curates, Fr. John Ullathorne, nephew of the

bishop, who also designed the decorations on the wall behind the

high altar. The altar and its reredos are carved from Caen stone.

There is also a carved marble altar rail that has survived the

edicts of the Second Vatican Council. |

The rear of

St. Mary and St. John. |

|

The

capitals of the pillars and the heads of the Apostles on the

corbels were carved by Mr. Shepherd of Bristol, who was probably

recommended by the architect who also came from that city. The

same artist probably carved the two portrait heads on the arch

at the entrance to the sacristy. They show two Popes, Pius IX2

who was reigning when the church was opened and Leo XIII, Pope

when the chancel was opened. In 1839 or 94, the Harrison family

furnished the Sacred Heart Chapel, paying for the altar, windows

and benches. The altar in both this and the Lady Chapel are of

Caen stone and were made by Wall of Cheltenham.

The

Victorian stained glass in St. Mary and John is particularly

impressive though binoculars are recommended to pick out some of

the detail in the higher reaches of the building.

We

begin at the Apse behind the High Altar. The three panels of the

window, by Hardman and Company, are High Gothic, with stylised

figures recalling medieval glass. Dark colours, particularly

blue and red, predominate. Both the three major scenes and the

smaller ones below have their own architectural canopies. The

central panel was the first to be installed in 1880. The mail

scene shows the Crucifixion, with the church’s dedicatees, St.

Mary and St. John, looking on. The panel showing the Adoration

of the Magi was installed in 1884. The smaller scenes below show

incidents from the life of the Virgin Mary. The panel showing

the Transfiguration was added in 1885. In all three scenes

Jesus’ hands are raised in blessing or suffering, bringing a

unifying gesture to the windows. Along the bottom runs a frieze

of saints and holy men, while the three lunettes above show an

angel with a star (since Mary is Queen of Heaven), Christ in

Glory and an angel with John’s Gospel.

The

church contains other fine examples of Hardman and Company

glass:

The

chapels of the North and South of the Chancel contain good

Gothic windows. The figures are less stylised than those in the

Apse window and represent a development of the Gothic style. The

North, or Lady, Chapel window was installed in 1890. It shows

three scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary: her mother

dedicates her to the service of the Temple, the Annunciation and

her coronation as Queen of Heaven crowned with seven stars.

The

window in the south, or Sacred Heart Chapel, which dates from

1892, shows three scenes from Christ’s Passion, while in the

lunettes angels hold the bread and wine of the Mass and Jesus

bares his Sacred Heart, burning with love for the world.

The

excellent Baptistery window illustrates a further development in

the adaptation of the Gothic. Although no reference to this

window could be traced in the Hardman archives before 1899, it

is of such high quality that it must surely be by the firm. The

panels still have Gothic canopies and stylised lilies in the

foliage, but the figures are depicted in a very naturalistic way

and we seem to see the faces of real people. The scenes here all

feature St. Joseph. We see the marriage of Mary and Joseph, the

Presentation in the Temple and Jesus and Joseph at work in the

carpenter’s shop. In a premonition of Jesus’ death, they are

making a cross. The lunette shows the death of Joseph, comforted

by Mary and Jesus. He is patron saint of all who desire a holy

death.

Lastly

a note about the problematic tower and spire that were never

completed. The proposed tower was to be 25 feet square at the

intersection of the south transept and chancel. Above the tower

there was to rise a spire, the total height being 225 feet. To

take the weight of the proposed tower, Hansom thickened the

pillars at the south side of the chancel arch, building inside

one small stairway. Some parishioners felt that that the spire

would be more imposing at the west end of the church. The

obliging Hansom widened the aisle buttresses on either side of

the south door, the entry door to this spire still remains. The

spire and tower remained a dream until the early years of the

20th century but it was never constructed. Although the building

does have an incomplete look we should be grateful that the

spire was not built, for it is doubtful if the fabric of the

building could have withstood the weight. The church was a

constant drain on parish expenses mainly due to problems with

the fabric.

|

|

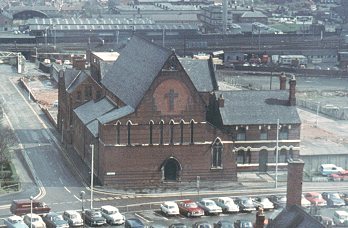

St. Patrick's Church, just before

demolition. |

A Roman

Catholic church that fell victim to the new Ring Road was St.

Patrick’s which once stood in Westbury Street. The church, which was

opened on the 21st May 1867 and had seating for 500, was to a design

by E.W. Pugin, son of the famous A.W.N. Pugin. As an expanding and

thriving town it was logical that Wolverhampton should attract

migrant workers. Many of these came to the town from Ireland,

especially County Galway, and these helped to swell the catholic

population, which by 1881 was reckoned to be 5,000. |

|

St.

Patrick’s was mainly concerned with serving this, hence the

name. When the new St. Patrick’s was built near New Cross

Hospital, some of the Victorian stained glass from the old

church was reused.

It is a

pity that due to the Ring Road and the decline of the Snowhill

area,3 Saint John’s Square is not as

frequently visited as it once was. This is sad for it is one of

the finest and most elegant spots in town. It also hides one of

Wolverhampton’s least known gems, that of the House of Mercy.

The Sisters of Mercy came to the town in 1848 and became

actively engaged in education, making themselves responsible for

five elementary schools and training pupil teachers. In 1858

they had a convent built on Snowhill, which was the centre of

their work looking after the poor. Sadly now the Sisters of

Mercy have departed and gone. The house itself is a Georgian

corner house but in George Street, there is an ashlared Gothic

brick range and behind, an added aisle-less chapel with a

polygonal apse; they are both by E.W. Pugin.

|

| The Church of

St. John itself does not qualify for this study, dating as it does

from 1758 to 1786. However it does contain some Victorian features

especially stained glass. Apart from two Gothic windows in the

Chancel, which do jar a little, the rest of the windows fit the

church’s classical style very well and exhibit a restraint unusual

in the Victorians. The glass is of a remarkably high quality. One

major London firm, Ward and Hughes, and one important local firm,

Camm of Smethwick, are represented. There are two Ward and Hughes

windows in the North and South aisles. That in the North aisle is

third from the west. It is signed and dated 1882. It shows King

David playing his harp, surrounded with what the Victorians thought

of as “antique” instruments. The window is a superb example of the

Aesthetic-influenced style, with soft classical draperies. |

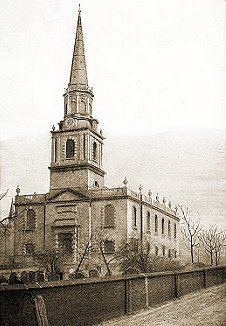

St. John's Church. |

|

The

window in the South Aisle (the easternmost before the chapel,

dated 1884) is magnificent. It shows Wisdom with her children.

Wisdom was personified by the Jews and the early Christians as a

woman. The noble and Junoesque figure of Wisdom holds a lily

while her children look on. The scene is surrounded by an

anthropomorphic Greek border.

The

chancel windows of 1852, in High Gothic style, are out of place

in this setting. They show the “Six Acts of Mercy” listed by

Jesus in Matthew’s Gospel. Each window is made up of three

circular medallions surrounded by foliage. Dark colours

predominate and in each an angel holds a banner with a teaching

of Jesus.

Other

Victorian glass can be seen in the South Aisle. From the east we

see:

The

Presentation in the Temple, obviously a very popular subject

with Victorian stained glass designers, since a version also

exits in St. Peter’s and St. Mary and John. The window is dated

1893 and is in the Aesthetic Style, but the artist is not known.

It is dedicated to George Higham (of the building firm that

worked on the restoration of St. Peter’s) by his “brother

masons” and Freemason symbols are much in evidence in the

border.

The

adjacent window, undated, was installed at the same time. It

shows Jesus, aged twelve, disputing in the temple with the

doctors of the law. It is an apt companion to the Masonic window

since the temple features largely in Masonic teaching. The

window is signed in the bottom left hand corner “Baguley”.

George Baguley (1834-1915) was proprietor of a stained glass

studio in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, established in 1867.

Lastly

in the South Aisle is a window of 1901, in memory of William

Garfield, who died in the Boer War. Appropriately for a soldier,

the window shows Jesus blessing the Roman centurion whose

servant he healed. This fine window is signed “S. Evans of

Smethwick”. This is probably Samuel Evans of Smethwick, whose

studio was in existence as early as 1879. Smethwick was a centre

for stained glass design, with workshops including those of

Chance Brothers and Camm in operation from the mid-19th century

until well into the 20th.

Indeed,

St. John has some examples of Camm glass, although they are from

the early 20th century and strictly outside the scope

of this book. Both can be seen in the North Aisle, the first two

windows from the west. The first, dated 1910, shows Jesus with

Mary and Martha. It is a fine window in the classical style.

Next to it is a superb example of the work of Florence Camm

(1847-1960), daughter of the founder of Camm and Co and

important craftswomen in the Arts and Crafts style. It shows

Jesus as the good shepherd.

The

Gallery has two further Victorian windows both dated 1880 and

unsigned. They are painted glass and have deteriorated over the

years. The South window shows the Resurrection while the North

has Faith, Hope and Charity. They are not vintage examples of

Victorian glass painting.

Also of

interest is the reredos and chancel panelling, pulpit and font,

the two former of 1899. There are in the church, many encaustic

tiles from the Minton factory given to St. John’s as a gift.

Those east of the altar have been carpeted over as have those of

the nave aisle, but many more examples are still to be seen.

Notes:

| 1. |

A gem

of Roman Catholic Church architecture is that of St Chad’s

at Brewood. It is also the only example in the area of the

work of A.N.W. Pugin. |

| 2. |

Pius

IX, or Pio Nono, is one of the best known Popes to

non-Catholics for it was he who was Pontiff during the

movement towards Italian unification. After the annexation

of Rome by the new state Pius famously declared that he was

a “prisoner of the Vatican”. After Pius, no Popes left the

Vatican until the signing of the Lateran Treaty in 1929.

More controversially, it was Pius who took personal charge

of Eduardo, the Jewish boy brought up a catholic because a

maid claimed to have secretly baptised him. |

| 3. |

Since

writing this the Snowhill area has been revitalised, the

shops de-cluttered and the whole street turned into an

attractive part of town. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Return to

Anglican Churches |

|

Return to the

contents |

|

Proceed to

The Chapel |

|