Chapter Two

Part Two

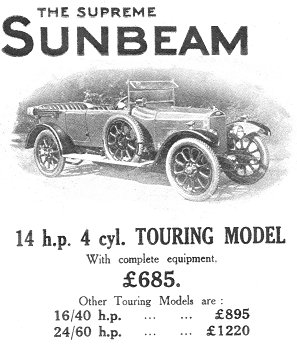

| Moving ahead now to 1907 in which

year the motor industry suffered its first slump. It can be

noted that Sunbeam weathered the storm much better than many

others. Frederick Eastmead entered a reliability trial in

Ireland with a 16/20 and completed the event without loss of

marks. |

|

For some years Sunbeam

cars had been fitted with Loyal multi tube radiators but from

1906 Marston ‘honeycombe’ radiators made under Megevets patents

were used and these would become one of the company’s major

products and continue in production long after vehicle

manufacture had ceased.

Though his 16/20 was

proving a success and bringing some fame to the

Wolverhampton firm Angus Shaw was hard at work on his next

project, a six cylinder engine with the same cylinder

dimensions as the four, with separately cast cylinders. The

chassis was made of ash, reinforced with steel girder

plates, having a wheelbase of 10' 4" and a track of 4' 4". |

|

Listed at £750 for the

chassis and £50 for a touring body, the Sunbeam appeared to be a

bit expensive and did not prove to be a success, soon being

withdrawn. Modifications were made to the 16/20 with the bore

and stroke being increased to 105 x 130mm giving the engine more

reserves of power for hill climbing, which was never a strong

feature on the earlier Sunbeams. This model became known as the

Twenty.

Shaw also designed a 120

x l40mm four cylinder 35h.p. car, priced at £675. There was

still some resistance at this sort of price and few were sold.

Some significant changes were about to take place at Sunbeam

when a famous French engineer joined the company. That story we

must leave until later. |

| During the period under review Star

had expanded and continued to grow. In 1905 they could offer

a comprehensive range of cars which included a twin cylinder

7h.p. model listed at £175, a four cylinder car at £260 as

well as several other models of up to 30h.p.

About this time there was a decline in

pedal cycle sales. Star were very large producers of these

machines so for 1905 the Star Cycle Company run by Edward

Lisle junior introduced the Starling, a cheap light car for

sale through their cycle agents. It had a single cylinder De

Dion like engine, two speed gear and chain drive, selling

for a modest £110. The following year a twin cylinder model

was brought out with three speeds and a shaft drive. Known

as the ‘Stuart’ these cheaper Stars continued until 1908

when the Stuart name was dropped and all the Star Cycle

Company cars became Starlings. |

|

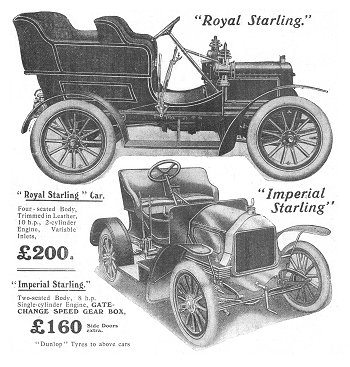

An advert from 1908. |

At the 1907 Cordingley

Show the Royal Starling had been shown and created a lot of

interest, being very much on the lines of the larger Stars.

Its twin cylinder engine had cylinder dimensions of 3.75" x

4.5", three speed gear, and a leather faced cone clutch. The

engine speed was controlled by variable lift inlet valves

operated by a wedge that could be slid in or out between

cams and valve tappets. Also exhibited were two Starlings

which were proving popular in view of their low price,

though this had now been upped to £120.

During 1909 the Starlings and Royal Starlings were dropped

and a new company, the Briton Motor Company was formed with

Edward Lisle junior in charge. Their policy was to produce

good quality light cars at a reasonable price. |

|

The cheaper Star models

would now be Britons and the 10h.p. twin cylinder car became

popular and sold in good numbers, but a 4 cylinder 10h.p. model

did not prove successful sales wise. At the A.G.M. of the Star

Cycle Company held at the Star & Garter Hotel on 29th January,

1909 the name was changed to the Star Engineering Company.

Star Engineering also

had a stand at the 1907 Cordingley Show and displayed their

first six cylinder car, a 30hp model with cylinder dimensions of

4.25" x 5", cast in pairs. Other features included a special

automatic carburettor, magneto ignition, and automatic oiling.

The three speed gearbox had direct drive on top.

Also on show was the

7h.p. that had been updated, a honeycomb radiator now replaced

the earlier gilled tube affair and the tubular front axle had

given way to one of ‘H’ section stamped steel. Star also proudly

displayed parts of a car they had supplied in February 1906 to

the Royal Automobile Club for use in teaching members and their

servants to drive. Over the following year the car ran l0,000

miles and something like 550 lessons were given. Quite an

arduous life, yet the cost of repairs and replacements during

that time were reported as nil.

The following month it

was considered expedient to dismantle the car for inspection.

Only very slight wear was found in the gears and only one big

end needed attention. Chains and chain wheels were also seen to

be in excellent shape and like the clutch good for many more

miles.

All this a wonderful

testimony to the fine workmanship and materials used in Star

cars, and the company made extensive use of it in their

advertisements. Much the centre of attraction on the Star stand

was a T.T. type l8h.p. car with side entrance Phaeton bodywork.

It was powered by a 4 cylinder engine with cylinders of 4.25" x

5" and included magneto ignition, and a four speed gearbox with

direct drive on top. |

|

This model was based on

cars entered in that years RAC Tourist Trophy races, a race Star

contested three times, unfortunately each time without success.

It would perhaps now be opportune to consider some of Star's

competition efforts. Edward Lisle had not at all been put off by

the lack of success of his car built for the 1903 Gordon Bennett

race and decided to try again in 1905. The 1904 race had been

won by Richard Thery driving a French Richard Brasier. The best

performance by a Briton had been Sidney Girling's 9th place on a

Wolseley. Charles Jarrott on a similar car claiming 12th place.

Two Stars were prepared

for the 1905 eliminating trials which were to be held in the

Isle of Man and would take the form of a race of about 300 miles

over the mountain circuit. Also taking part would be four

Napiers, two Wolseleys a Siddley and a Wier Darraque.

|

An advert from 1909. |

|

Star suffered an early

misfortune when Joe Lisle had been involved in an accident on

Tettenhall Road, Wolverhampton whilst testing one of the race

cars. He was heavily fined and disqualified from driving. Due to

this the organising club would not permit him to drive in the

trials. Edward Lisle then engaged two brothers H. and F.

Goodwin. Both were Star cycle agents and whilst they were well

known as first class cycle racers they were complete novices

when it came to motor racing. It is said that one had to be

taught to drive before he could enter the trials. The cars were

very much like contemporary Mercedes with four cylinders cast in

pairs and dimensions of 139.7 x 165.1mm. They developed 90b.h.p.

and had a four speed gearbox with a Hele Shaw spiral spring

clutch and final drive by side chains. In its report 'Autocar'

said they were splendid machines, fine examples of engineering

and with almost every part made in the Wolverhampton works.

In the eliminating

trials Napiers were the cars to beat. Over the flying half-mile

Arthur Macdonald recorded 88.2m.p.h. and F. Goodwin could only

manage 50m.p.h. on his Star. Unfortunately his brother had a lot

of problems with leaking water jackets on his car. In the

eliminating race only two cars completed the 300 miles; Clifford

Earp's Napier and the Wolseley driven by Cecil Bianchi. H.

Goodwin had managed to complete five of the six laps and was up

to 6th place when forced out with mechanical trouble. F. Goodwin

had also been in 6th spot at one time but fell out after three

laps, including the fastest lap by a Star at 38.6m.p.h. The

fastest lap of the day had fallen to Cecil Edge on a Napier with

a speed of 56m.p.h.

The team chosen to

represent England in the 1905 Gordon Bennett race were Earp

on a Napier, Rolls and Bianchi on Wolseleys, and Cecil Edge

and John Hargreaves on Napiers. In the race Theray again won

for France on his Richard Brasier. Rolls proved to be best

of the British team bringing his Wolseley into 8th place

with Earp next and Bianchi 11th. This would prove to be the

last Gordon Bennett race for cars, the following year it

would be for balloons and from 1909 for aeroplanes.

|

|

Harry Goodwin's 70h.p. Star racer from

1905. |

Earlier reference was

made to the RAC Tourist Trophy races. These were to become very

famous events that were first held in 1905 in the Isle of Man.

The course was very similar to the one used from 1911 to the

present day for the Auto Cycle Unions Tourist Trophy motorcycle

races. Although Wolverhampton cars would perform well in the

former they would not enjoy the great successes of the

Wolverhampton motor cycle factories in later years. Two modified

Star touring cars were entered for the 1906 T.T. but both

retired about 50 miles from the finish when they ran out of

petrol. They had not been well placed during the race.

The race was won by Hon. Charles Rolls driving a Rolls Royce at

an average speed of 39.43m.p.h. for the 161 miles. Despite this

poor showing Star were back again for the 1906 race with two

cars. |

|

They were four cylinder

102 x 127mm with an RAC rating of 25.5h.p. Reports referred to

them as rather pretty cars. In the race Prew crashed at Quater

Bridge through unsuitable tyres for the very wet conditions

under which the race was run. The other Star was also forced to

retire. Though the Wolverhampton cars had not shown up well,

people who had been or would be connected with the towns

industry did quite well. Thomas Pullinger late of Sunbeam

finished 5th driving a Beeston Humber of which he was designer.

Louis Coatalen, who we have yet to meet as Chief Engineer at

Sunbeam was 6th on a Coventry Humber, and Algernon Lee Guiness

who with his brother Kenelm would be famous as racing drivers of

Sunbeam cars took 3rd spot in a Darraque.

Before leaving Star for

the time being it is well to note that Mr. Edward Lisle founder

and Managing Director was a highly respected figure in both the

cycle and motor trades. Mr. Lisle was a very straight forward

and astute business man, so that when cycle sales fell he

entered into car manufacture and did quite well. Also later he

introduced cheap cars for his agents to sell, again with marked

success. When it had been decided to produce the extra products

Mr. Lisle did not reform the company and did not ask his

shareholders for more cash, putting up considerable sums of his

own money to carry the firm over the difficult period. That this

paid off is shown in reports in the motoring and cycle trades

press, they could report profits in the order of £10,000 in 1910

with every chance of these being doubled in the very near

future. |

|

|

|

Return to

Part 1 |

Return to

the beginning |

Proceed to

Part 3 |

|