|

Another underground fire started at

Sparrows Forge Road in 1902 which resulted in a crowning

in. A similar fire broke out behind the Old Park Works

in 1911 which resulted in a horse being swallowed up. As

recently as June 1935 another underground fire took

place in Old Park Road.

Lodge

Holes Colliery, like many of the local coal mines,

caused subsidence in the surrounding area. Some of the tunnels in the coal mine were

under Dangerfield Lane, which caused part of the road to

subside. Wednesbury Corporation was left with the job of

restoring the road to its original level to make it

useable again. On the 30th June, 1908, the Corporation

sought damages from the colliery owners to cover the

cost of the repairs to the road, including raising it to

its original level. The owners had refused to cover the

full cost, stating that it would be far cheaper to

repair the road, leaving it at the sunken level.

Wednesbury

Corporation went to the Court of Appeal in the Royal

Courts of Justice to force the colliery owners to pay

the full amount for the necessary work. The Corporation

were unsuccessful in their appeal and were told that the

sum of £80 offered by the colliery owners would be

sufficient. In order to restore the road to its original

level and to properly support it, involved the building

of an embankment and retaining walls, which cost the

Corporation around £400. Details of some of the local mines

can be seen in the list compiled in 1896 by W. Beattie

Scott, H.M. Inspector for the South Stafford District:

|

Mine |

Owner |

Underground workers |

Surface workers |

|

Blakeley Wood |

Price and Son, Leabrook |

38 |

26 |

| Coal

Hall

|

David Read, Darlaston Road |

|

|

| Far

Close |

Roberts and Parkes,

Wednesbury Bridge |

|

|

| Hobbs

Hole |

Hobbs Hole Colliery Co. |

12 |

5 |

|

Hollow Meadow

|

Smith, Round & Ramsall,

Hollow Meadow |

|

|

| Lodge

Holes |

Wednesbury Henry

Bird, Butcroft, Darlaston |

5 |

3 |

|

Millfield |

Patent Shaft and Axletree

Co. |

114 |

76 |

|

Moorcroft |

Moorcroft Colliery Co.,

Moxley |

20 |

7 |

|

Moorcroft |

G.W. Bray, Moxley |

5 |

3 |

| Old

Park Road |

Hobbs Hole Colliery Co.,

Wednesbury |

16 |

5 |

|

Wednesbury, Old Fields |

Bradshaw and Bailey, West

Bromwich |

3 |

2 |

|

Wednesbury, Old Park |

Jas. and Jno. Hunt, King's

Hill |

13 |

4 |

At Old Park

Colliery, run by Lloyds and Fosters, they raised coal

from a depth of 200ft, most of which was used in the Old

Park Works. Other mines were run by:

|

Samual Addison

|

|

John Bagnall & Sons |

|

Simeon Constable |

|

Danks & Company |

|

Edward Wright & Company |

Coal mining in the town began to

decline in the second half of the 19th century, at a

time when coal could easily be transported from other

areas, thanks to the extensive transport infrastructure.

The main competition came from the Cannock area, and the

following neighbouring towns:

|

Town |

Number of collieries |

|

Bilston |

64 |

|

Walsall |

39 |

| West

Bromwich |

52 |

|

Wolverhampton |

26 |

The collieries in West Bromwich were all built during

the 19th century. At the time there were 21 working pits

in Wednesbury, including Balls Hill Colliery, run by

Lloyds and Fosters, and Lion Colliery at the Mounts.

Both of them were producing the best coking coal in

Staffordshire for the iron smelters and the gas

companies.

An advert from 1897.

By the end of the 19th

century, only a few pits survived, and within a short

time they too would disappear as they became

uneconomical to work. The last were the Millpool

Colliery which closed in 1914, and the Millfield

Colliery which closed in 1915. Both were owned by the

Patent Shaft.

An interesting account of local

coal mining can be found in "Osborne's Guide to the

Grand Junction Railway" published in 1838:

Wednesbury is about a mile and a

half to the west of the line, and two miles further

north than West Bromwich. It was, very early in the

history of our country, a place of importance; its name

being derived from Woden, the God of war of the Saxons,

and Boro or Burgo, the name of a town. In the year 900,

there was a strong fortress erected here, on the hill

where the church stands now. The place stands on a hill,

and is surrounded by the scenery of tall chimneys,

engine houses, the machinery of coal pits, furnaces, and

iron works. It is a dark, dirty, mean-looking place, as

though cleanliness and comfort were none of its care.

The population is 9,000 or more. The church is a

handsome Gothic building, lately repaired at an expense

of £5,000. The living is a vicarage, in gift of the

crown. There are three chapels. One belonging to

the Independents, one belonging to the Methodists, and

one to the Primitive Methodists. This is one of the

places that furnished such furious mobs, when first the

Wesleyans began their out-door preaching.

There is a Lancasterian School,

built by subscription, for educating 130 boys, a Church

Sunday School, and a Methodist School. There are about

£68 per annum arising from land and legacies, for

charitable purposes: and the Poor Rates amount to more

than £2,300.

The mines of coal, iron, and

lime, and the manufacture of iron into gun locks and

barrels, axle-trees and springs for coaches, hinges,

nails, screws, files, gas and water tubing, afford the

population tolerably full employment. The whole country

round about seems turned inside out: it is worked in all

directions for ironstone, coal, and limestone.

The pits vary in depth from 60

to 300 yards. It is extremely interesting to go down one

of these pits; and if the visitor resolves to descending

one, he had better select one that is deep, and has been

in work for some time. He will be furnished with a

miner's jacket, trousers, and cap, and accompanied by a

guide, and will get into a large iron basket fastened by

hooks and chains to the rope, the iron basket resting on

the lid of the pit. The rope is gently drawn up, and the

lid rolled away, when the experimenter finds himself

suspended over a perpendicular descent of 200 yards. The

engine begins to turn, and he descends into the shaft,

which becomes increasingly dark, and the candle which he

carries with him scarcely serves to light him to see the

moving darkness. As he passes down, he will observe the

different strata, and most probably will see the

openings of mines which have been worked in the course

of the sinking of the pit. The sensation which he will

experience, from the sides of the pit rapidly ascending

past him, while he feels himself as rapidly sinking, is

one which is very awful and interesting, and must be

experienced to be understood. To feel that you are fast

sinking into the bowels of the earth, and that the light

of heaven and the beauty of earth are receding from you,

and may never more appear, is one of those sensations

which brings all the natural dread of eternity nearer to

us than we probably ever experienced before. On arriving

at the bottom, you step out, and following your guide,

you discover some dim shadowy beings, by means of the

lights placed around, who are engaged in boring and

digging the solid rock.

But now you turn your eyes up to

look what is the roof over your head: and there you see

the massive and eternal rock, and remember that you are

two hundred yards beneath the surface of the earth. What

a situation would it be for one being alone! On looking

round, you perceive (if it be a limestone pit,) a lofty

roof, eight or ten yards high, of apparently veined

marble, sustained by massive and handsomely formed

pillars, at the distance of every ten or twelve yards.

These pillars are parts of the rock, which have been

left in the working, and yet they have all the

appearance of having been constructed. In some places

you see men lying down, working with pick axes, clearing

away the obstructions; in others you see them boring the

rock by driving immense chisels into it; and in some

places you see them upon ladders, doing the same work at

the roof. Anon they inform you they are going to blast a

portion of the stone off. You retire behind a pillar,

and the terrific explosion thunders in reverberating

volleys through the mine. Again and again does the blast

burst in astonishment upon your ears. On examining the

place after an explosion, you find a large mass of rock

split off, sometimes a ton in weight. Such is the power

of the expansion of heated air.

In some places you find the

water drains through the rock into the mine; and the

mouth of the pit is always dropping, so that the mine

would soon be full of water, if it were not for the pump

which is always kept at work in the other shaft. The air

is very agreeable, and when the eye is accustomed to the

dullness of the light, and can distinguish clearly what

is going on, the mine is really very pleasant; for the

temperature is quite comfortable, and all the fear of

your position is gone in the course of half an hour.

After seeing the loading of the basket occasionally, you

at length step in yourself and ascend, returning to the

surface of the earth again.

It is lamentable to find, that

this population scarcely ever thinks of anything but

eating and drinking when the day's labour is over. The

house of the working man is not much inhabited by him.

The mine has his days, and the ale-house his evenings.

He cares not for his family. The wife may care if she

will; but she was brought up in a house of the same

kind, and what else can be expected of her.

The women in this neighbourhood

seldom wear caps. They mostly use a handkerchief tied

round their head, and neither in person or manner show

much of grace, or attraction. They are early used to

carry heavy burdens, and help to load and unload at the

mouth of the pit; hence they become coarse and unwieldy,

and lose that natural pleasantness, if not gracefulness

of appearance, which is common to their sex. This is

particularly observable in the extreme width of their

mouths, shortness of the necks, and breadth of their

shoulders, caused by the habit of carrying heavy baskets

of coal on their heads from the shafts of the pits to

their respective dwellings, there being a regular

allowance to each workman for his individual home

consumption.

There is a market every Friday,

and a fair on the 6th of May, and the 3rd of August.

There is also a wake or feast, which begins on the

Sunday before Bartholomew's day. The wake, especially,

is a terrible time for the display of the propensity to

drunkenness. During the war most of the men might have

become independent, so high were their wages, and so

constant was their employ; but after all, few of them

are possessed of common necessaries.

|

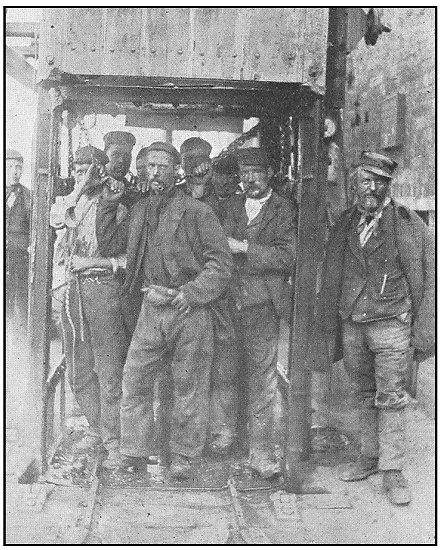

From the 1900 edition of

Ryder's Annual. |

|

Other Industries

The Quarter Session Rolls from

around the end of the 16th century includes a

list of the inhabitants of Wednesbury who ended up in

court. It also includes their occupations which were:

| alehouse keeper,

baker, blacksmith, bridle / saddle maker,

buckle maker, butcher, carrier, draper,

farmer, ironmonger, iron worker, joiner,

labourer, miller, nailer, peddler or

merchant, potter, servant, spur maker,

weaver |

The burials recorded in the Parish

Registers from 1678 to 1699 include the occupations of

the deceased as follows:

| 2 bakers, 3

blacksmiths, 7 brick makers, 3 buckle

makers, 3 butchers, 6 carpenters and

joiners, |

| 3 cobblers, 73

colliers, 2 edge tool makers, 5 farmers, 2

glove makers, 2 iron fitters, |

| 2 ironmongers, 10 labourers, 4 locksmiths, 1

maltster, 3 masons, 6 millers, 83 nailers, |

| 2 peddlers or merchants, 8 potters, 2

servants, 2 textile dealers, 3 weavers, 1

wheelwright |

It is interesting to compare the numbers of people

involved in the different industries listed in the above

table. Most of the workers were nail makers or coal

miners, showing the importance of both of the industries

at the time. Nearly 3% of the working population were

brick makers, and 3.4% were potters. The local pottery

became known as "Wedgebury ware" and was sold throughout

the region.

Clay tobacco pipes were also made using white clay from

Monway Field.

In 1776 Wednesbury had its own silversmith in the

form of John Whitehouse who produced many items

including buckles, seals and tea tongs.

Pottery

Pottery was one of the town’s

earliest industries. It dates back to at least the early

1400s. Two potters, Geoffery Mosard and Thomas Brerely

are mentioned in 1422 as defendants in a case, listed in

a deed from 1423, that’s in the William Salt Library.

The industry is also mentioned by Robert Plot in his

‘Natural History of Staffordshire’ published in 1686. He

wrote that there were two kinds of clay dug in Monway

Field, on the west side of the town, that were used in

combination to make pottery that was painted with a slip

made from a reddish earth found at Tipton. One type of

clay was a yellowish colour that was mixed with white

clay, which was stiff and weighty. The other type of

clay was bluish, light and more friable. They were an

ideal combination when mixed together. The pottery was

baked in round ovens that were over eight feet high and

six feet wide.

Wednesbury pottery was sold as far

away as Bromsgrove where it was mentioned in wills

between 1606 and 1695. When the site of Oakeswell Hall

was excavated in 1983, large pieces of broken pottery

were found that dated from the fifteenth to the

seventeenth century. Thee finds included vessels that

had been incorrectly fired in a pottery kiln and some

clay saggers. Similar vessels have been found in the

local area and at Lichfield and Birmingham.

In 1988 excavations were carried

out in Ridding Lane following the discovery of small

oval pits containing fragments of pottery and saggers,

which must have been kilns. There was also a large

rectangular hollow from where clay was dug. Traces of a

pottery kiln were found in 1989 when a row of shops in

the Market Place were demolished. The kiln was lined

with stone and had a clay dome. There were saggers and

broken pottery including black-glazed cups and beakers,

large bowls, yellow glazed cups and dishes,

The industry died-out around the

end of the eighteenth century, except for common brown

stoneware which was produced at Lea Brook until at least

the early 1900s. The pottery industry was quite

significant and is remembered thanks to Potters’ Lane.

One of the large potteries there belonged to Thomas

Allen. It was put-up for sale in 1800 along with all of

its utensils. Another pottery works was for sale in

1789. It stood in Monway Field and belonged to Thomas

Mills. The pottery produced coarse earthenware which was

described by Frederick William Hackwood in his

‘Wednesbury Papers’, published by Robert Ryder in 1884,

as “hand moulded, of very dark greenish brown clay, not

at all very well baked and poorly glazed in parts”.

The remains of local pottery

excavated in the town include two-handled drinking cups

found at Church Hill. Plot also mentions the production

of arched bricks for use in coal pits.

Nail

Making

Nail making began at Wednesbury in about 1500 as a

cottage industry. The nail makers relied on the

ironmonger, the middle-man who supplied them with iron

rod and then purchased the finished nails from them,

often for tokens instead of cash. The nailers mainly

worked in outbuildings next to their cottages and were

self-employed, usually working long hours for little

reward. |