| The Growth of the

Town

As in the neighbouring towns, the population greatly

increased in the 19th century thanks to the availability

of employment in the new industries. This can be seen

from the census records:

|

Although the population had greatly increased, the

town centre where most people lived, still occupied a

relatively small area around Trouse Lane, Upper and

Lower High Street and Bridge Street. Many of the houses

were tightly packed and others were at the back of

courtyards. |

The Market and Entertainment

The town became well known for its market, whose

roots go back to the 18th century. It all began in 1709

when Queen Anne granted a charter that

gave John Hoo the right to hold two annual fairs in the

town and a weekly market on Fridays. Fairs were

initially held on 25th April and 23rd July until the

calendar was altered in 1752, when the dates became 6th

May and 3rd August. The charter allowed the

sale of cattle, beasts, and all manner of goods,

including wares, and merchandise commonly bought in

fairs and markets.

At the time

John Hoo was lord of the manor, having purchased the

estate from the Shelton family. He was born around 1658

and became a member of the Bar and afterwards a

sergeant-at-law. He married Mary Hanbury of Whorestone,

Bewdley.

|

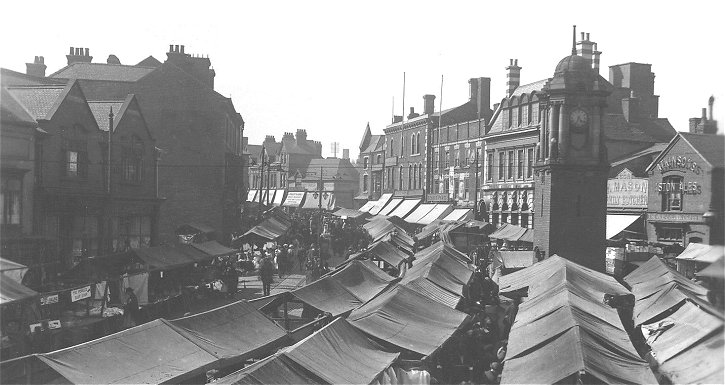

Looking into the Market Place.

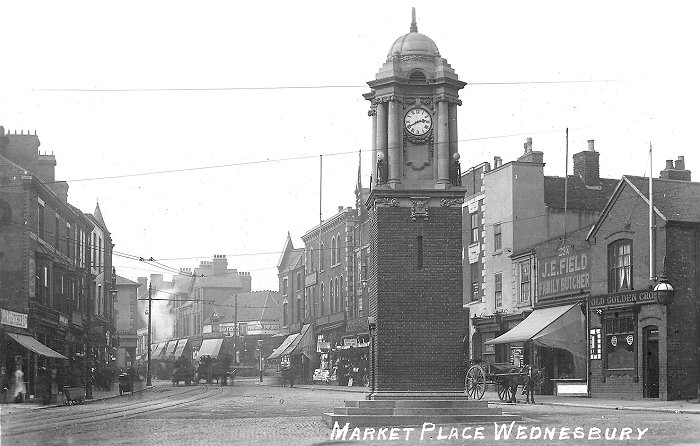

The Market Place in 1908.

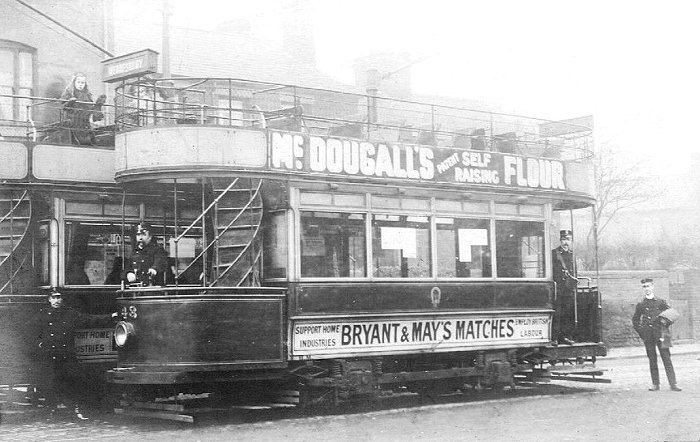

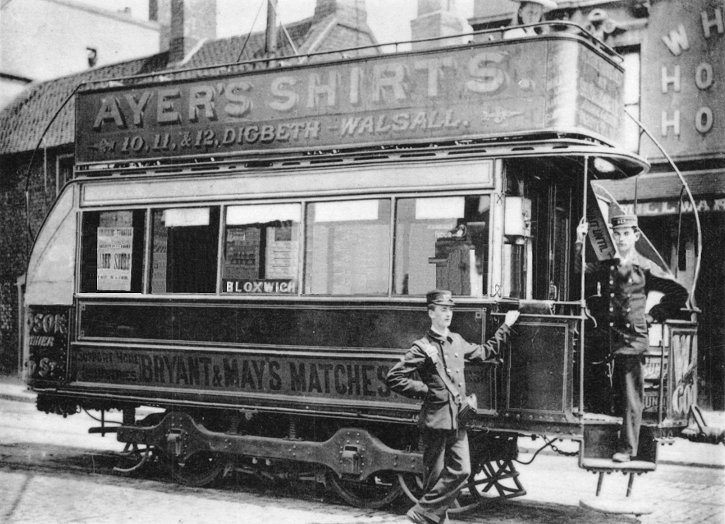

A tram on its way to Wednesbury. From an

old postcard.

| The market

cross building, possibly built in 1709, used to stand

approximately on the site of the present clock tower.

It

consisted of two rooms in an upper floor, resting on

pillars and arches. The rooms were reached by an

external flight of stairs on the northern side of the

building which were also used as a whipping post.

Offenders would be tied to the door posts and a public

flogging would be administered by the beadle.

The building

had many other uses. The Charity School, the Court of

Requests, and the Petty Sessions were all held there. By

1824 the building had been demolished after falling into

a bad state of repair.

By the early 19th

century Wednesbury

fair was in decline due to competition from

Walsall

and Wolverhampton.

By the 1850s the meat and cattle had gone and the fair

soon disappeared. The weekly market however, continued

to flourish in the Market Place until recent times. By

the early 19th century the Friday market had been

supplemented by the addition of a market on Saturdays.

In 1861 the market was purchased by the Local Board of

Health who fixed the trading hours as 5a.m. to 5p.m. on

Fridays and 12 noon until 11p.m. on Saturdays.

Today the Market Place is well

known for its fine clock tower which was designed by

local architect Mr. C. W. D. Joynson and built in 1911

to celebrate the coronation of King George V.

|

|

|

|

|

Wednesbury's Coronation Clock Tower. |

|

Laying

the clock tower's foundation stone on 22nd June,

1911. |

|

|

The dedication of the clock tower.

9th November, 1911. |

|

F. W. Hackwood

recalled in his “Wednesbury Ancient and Modern”, that he

was told of the sale of a wife, by an eyewitness, which

took place at a public auction held in the Market Place.

He also stated that this had happened on more than one

occasion.

The town also held an annual wake

on 23rd August, St. Bartholomew's Eve. When the modern

calendar was adopted in 1752 the wake moved to the first

week in September. Thousands of visitors flocked to the

town during wake week which became the local working

man's annual holiday. The wake extended from the High Bullen, through the Market Place to Bridge Street. |

| It greatly annoyed the local

factory owners because their employees were away from

work that week and so there was no production. In 1874

Richard Williams, the Managing Director of the Patent

Shaft, the town's largest employer became Chairman of

the Wednesbury Local Board of Health. He was determined

to end the wake and with the backing of the local

Nonconformist church he convinced the Board to obtain a

Home Office Order to abolish the wake. From January 1874

the wake was not allowed to be held on the streets, but

the resourceful organisers moved the event to the Back

Field behind the Green Dragon in the Market Place.

Richard Williams became the most unpopular man in the

town, and the wake became a tradition that continued for

many years.

Bull baiting was held during the

wake, initially at the High Bullen, and later in Back

Field,

with as many as 6 bulls being bated each year.

Many of the participators wore long white aprons which

extended to the ground and were used to catch their dogs

after they had received a tossing from the bull. The

baited bulls would be killed and cut up on the Thursday

of wake week to provide cheap meat for some of the many

visitors who had by then spent most of their money.

Several of the town's public

houses could also be found in the Market Place. They

were the Talbot, the George & Dragon, the White Lion,

and the Green Dragon. In Bridge Street was the Red Lion,

the Coach and Horses (later known as the Coachmaker's

Arms), and the White Horse. In Vicarage Road is the

Leathern Bottle which claims to date from around 1510

and so is the town's oldest pub, which was rebuilt in

1913. In the 18th century the magistrates met there.

The Old Leathern Bottle.

|

|

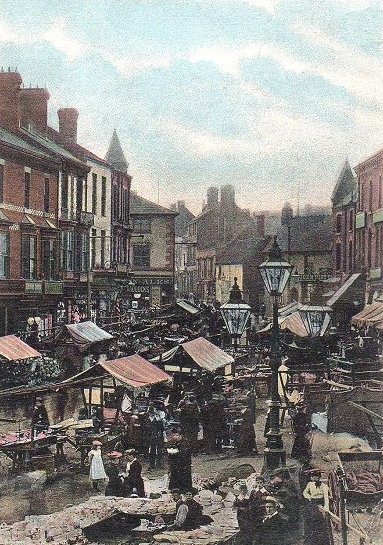

A busy day in the market. |

Other pubs included the Duke of

York, and the Turk's Head, which is still to be found in

Lower High Street. Other survivors include the George in

Upper High Street, originally known as the King's Head

and the Blue Ball at Hall End, which is now listed and

known as Spittles. Several generations of the Spittle

family ran the pub and also sponsored local cockfights.

Cockfighting was

a popular pastime, and in the 19th century

there used to be a cock pit in Potters Lane. Birds were

reared and trained for the king, and annual “cockings”

were held at Wake time. They were attended by the

nobility and members of the sporting fraternity from all

over the country.

Other sports included bear baiting,

and badger drawing.Horse race

meetings were held in Monway Field in 1778. They later

moved to a new course, and each meeting was followed by

a ball.

Other activities included dog fighting, prize

fighting, flower shows and a visit to the Theatre Royal

in Earps Lane, which opened in 1859.

|

|

The Market Place. From an old

postcard. |

|

Wednesbury had a 9 hole golf club,

founded in 1908 in Hydes Road on land leased from the

Patent Shaft. In 1938 the company attempted to sell the

land to a private property developer, but the attempt

failed because of the onset of war.

In 1947 the council

purchased the land and built the

Golf Links Estate, consisting of Woden Road South ,

Chestnut Road, Cherry Lane, Yew Tree Lane, Lilac Grove,

Walnut Lane, Cedar Road and Sycamore Road.

The Old Theatre Royal in Earps Lane

opened in 1859 and later became the Rialto Cinema. In

the 1960s it became the Midland Cinema Bingo Club but

soon closed, and was demolished in 1969.

Another

theatre, the Hippodrome Theatre in Upper High Street

opened in 1891 as the New Theatre Royal. It survived

until April 1959 and was demolished in the early 1960s.

The Picture House opened in Walsall

Street on 25th March, 1915. In 1938 its name was changed

to the Gaumont and in 1964 it became the Odeon. It had

another name change in the early 1970s when it became

the Silver and is now Walkers Bingo. |

|

Cholera

Cholera first

appeared locally at Bilston on 4th August, 1832 and

reached Wednesbury 5 days later. During the next two

months or so there were 285 cases in the town, and 95

deaths. The last case was reported on 12th

October. During the epidemic a temporary local board of

health was established, and the British School converted

into a hospital. 5 stations were set up for the

dispensing of medicine to the poor, and two medical

inspectors were engaged to provide daily reports on the

condition of people in the lodging houses.

A second

epidemic occurred in 1848 which resulted in 200 deaths

in the town. The Wednesbury Board of Surveyors erected

several huts on Monway Field for use as a temporary

hospital and a general undertaker was appointed for the

dead.

Each day the victim’s bodies were brought to the

church porch and buried in a communal grave. Many of the

cases occurred in St. James’ Parish, the poorest part of

the town. After the second

epidemic, the situation was taken in hand. In 1853 the

South Staffordshire Waterworks company was formed to

provide a clean and therefore safe water supply, to

prevent further outbreaks of the infectious disease.

Bridge Street looking towards

Lower High Street.

Another view of the bottom of

Lower High Street and the White Horse Hotel.

A tram outside the White Horse

Hotel. From an old postcard.

Another view of Lloyds Bank.

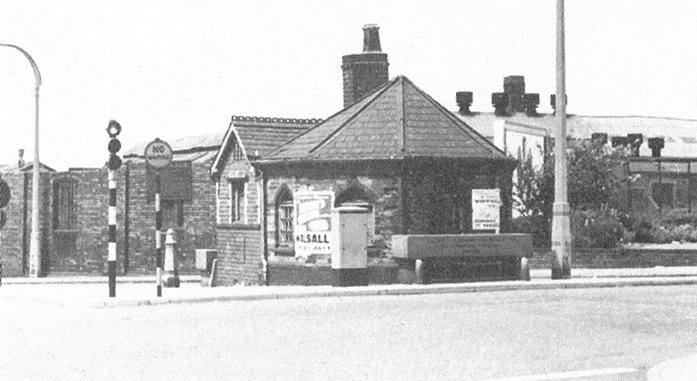

The toilets and horse trough at

the High Bullen.

|

In 1858 land was

acquired on Church Hill for the building of the

reservoir for the South Staffordshire Waterworks

Company. Work got underway in 1859 on the circular

reservoir which had an earth embankment, and could hold

1,538,190 gallons of water. It was 18 feet deep. By

November 1859, work on the reservoir itself had been

completed, allowing it to be part-filled. It came into

use in April 1861 when the project had been completed.

The work had been carried out by John Boys Limited.

In 1908 it was

recommended that the reservoir should be covered. It

remained open until 1923 when a roof, supported by 96

piers was built by Messrs. Davey & Company of Runcorn.

The reservoir continued in use until 14th May, 1974,

after which the site was sold.

Truck Shops

Many local factories used to pay using

the truck system in which workers received

vouchers instead of cash.

The vouchers could only be spent at the

factory owner's shop.

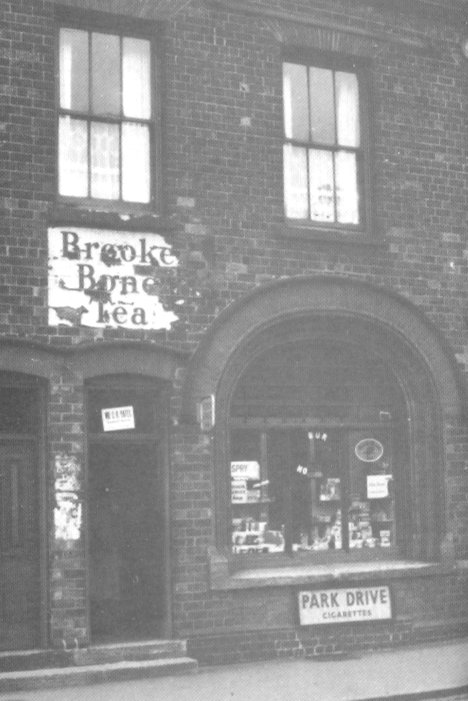

The shop in the photo opposite was once

one of these shops that was used by workers

from the Old Park Iron Works.

The Truck system was eventually made

illegal thanks to the Truck Acts which were

Passed in between 1831 and 1896. |

An ex-truck shop in

Manor House Road. |

Care of the Poor

By the turn of

the 17th century the parish was made

responsible for the well being of the poor thanks to the

Statute of Labourers in 1563, and the Poor Laws of 1598

and 1601. It became the annual duty of the parish to

choose an officer, usually around Easter, to administer

the Poor Law for the forthcoming year. The officer was

chosen at a vestry meeting and his name would be

submitted to a Justice of the Peace for approval. He

then had the power to raise taxes to supply funds for

relief of the poor. At the end of the year he had to

submit his accounts for the approval of the vestry. This

system lasted until the Poor Law Amendment Act of

1834 when a new system based on unions of parishes was

introduced. As a result Wednesbury parish became part of

the West Bromwich Union, run by a board of elected

guardians.

Wednesbury had its first almshouse

as early as the beginning of the 17th century

thanks to the bequest of Thomas Parkes, who died in

1802. He left £10 in his will for the care of the poor,

under the control of the vicar and churchwardens, who

were to pay £1 annually for ten years. He also gave a

house to accommodate a school for 10 poor children and a

cottage to be used as an almshouse for 2 persons.

Another bequest that provided money

for the poor was made in 1683 by Joseph Hopkins, an

ironmonger of Birmingham. He bequeathed £200 for the

purchase of land, in or near Wednesbury. Any money

earned from the land was to be given to help the poor.

The executor John Cotterell purchased 16 acres of land

in Darlaston and used its income to provide 3 coats and

3 gowns annually for 6 poor parishioners. The remainder

of the income provided bread and money for the other

poor inhabitants. The income greatly increased when coal

was found on the site. In 1823 it had risen to over £60

and provided 60 people with coats and gowns.

By the 18th century opinion had turned

away from almshouses, in favour of workhouses. The idea

was that the poor should earn their keep, and the threat

of the workhouse would act as a deterrent to anyone

seeking help, other than to those really in need.

|

| By 1766 Wednesbury had acquired its first workhouse

consisting of four converted cottages in Meeting Street.

The cottages were purchased by John Addenbrooke and John

Cox in 1715, using the proceeds from a special rate

levied for the help of the poor. At least one of the cottages became an almshouse and

all four were converted into a workhouse within a few

years. By 1768 a small cell had been added for the

custody of any wrong offender in the parish, but in

practice it was rarely used. The governor’s favoured

method of punishment was to chain wrong doers to the

fire grates. |

|

In 1786 an inventory of the goods

in the workhouse included a list of the rooms, which

consisted of the following:

| The governor’s

kitchen, a cellar, a bedroom over the pantry

with 2 beds, a lower house and men’s ward, a

lower parlour, a men’s lodging room with 12

beds, a woman’s kitchen, a women’s lodging

room with 20 beds, a brewhouse and a bedroom

above, with 2 spare beds. |

Little regular

work was found for the inmates, although occasionally

they were hired out to local employers. The workhouse

continued in use until 1857, when it closed. As already

mentioned, Wednesbury became part of the West

Bromwich Union as the result of the

Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834. The union was declared

on 11th October, 1836 and included the following

parishes:

|

Handsworth with Soho and Perry Barr,

Wednesbury, West Bromwich, Oldbury, Warley

Salop, and Warley Wigorn. |

Pressure for

accommodation mounted and so the commissioners

eventually decided to build a new Union Workhouse in

Hallam Street, West Bromwich, which opened in 1858. The

old workhouse building at Wednesbury remained until 1920

when it was demolished.

Health and

Sanitation

The 2nd Report of the Commissioners

on the Enquiry of the Health of Towns, published in 1845

states:

Wednesbury consists of one long

street, along the turnpike road, with many lateral ones

branching into courts and alleys, inhabited by the

working classes. There is no drainage worth the name, no

scavengers or system of cleansing, and the supply of

water very scarce and indifferent. There are no pipes

(though there is, it is said, a good supply near it, at

a high level above the town), a few pumps, and the wells

are often bad. The people complain much, and have to

carry water near a mile, or to buy at a halfpenny for

three cans.

The workhouse of the town has

very bad water in the well, and they are obliged to

fetch it for washing or drinking several times a day.

The courts, alleys, and small streets are unpaved or ill

paved, full of stagnant puddles, privies with open

vaults, pigsties, etc.; there is, in fact, no care taken

on these points, and the greatest neglect appears. I

find it stated "There is a dreadful stinking tank or

ditch at the back of the Turk's Head, where the

magistrates always meet, and the public enter by this

filthy place."

The damning report includes

footnotes on certain parts of the town:

|

Whitehouse Square |

Filthy choked-up privies,

and dirt holes overflowing. |

|

High Bullen |

Open drains, full and

stinking. |

|

Ledbury's Buildings |

Filthy open privies,

stagnant liquid filth and receptacles; bad

water generally; opposite court - bad

privies. |

|

Houses opposite Turk's

Head |

Open receptacle of liquid

filth. |

|

Miss Webley's Court |

Green stagnant puddles. |

|

Bullock's Fold |

Open terrible drains; no

water but by buying. |

|

Buck's Buildings |

Open privies, pigsties,

filth and ashes; open drain full of filth. |

|

Workhouse Fold |

Three had the fever in our

house, said a woman. One died; privy full,

filth overflows. |

Clearly something had to be done.

Of course the terrible findings didn't just apply to

Wednesbury, most towns and cities were much the same.

During the cholera epidemic which swept through England

from 1847 to 1849 the government established the General

Board of Health under the terms of the Public Health Act

of 1848. The new authority designated areas as local

health districts. If an area was not a borough it was

given the task of electing a local board of health to

oversee health and sanitation.

| |

|

| Read the story

of one of Wednesbury's most influential

families, The Lloyds |

|

| |

|

The Wednesbury Local Board of

Health was formed on 26th December, 1851 and held its

first meeting on 14th February, 1852. The original

members were:

| Rev. Isaac

Clarkson - Chairman |

| Thomas walker |

| J. N. Bagnall |

| Edward Elwell jnr. |

| Benjamin Round |

| Joseph Smith |

| Jesse Whitehouse |

| James Frost |

| Samuel Lloyd, who

became chairman in 1853 |

The Board's powers to improve sanitation were wide

and included:

| Regulation of

sewers, drains, wells, and the disposal of

refuse. |

| Regulation of

highways, slaughterhouses, and lodging

houses. |

| Regulation to

ensure the provision of adequate supplies of

water and gas. |

| The provision of

burial and recreation grounds. |

The following officers were appointed by the Board:

|

Clerk - |

Francis Woodward |

|

Officer of Health - |

Dr. Palin |

Surveyor and Inspector

of Nuisances - |

John

W. Fereday |

|

Treasurer - |

Henry Williams |

|

Collector of Rates - |

John Griffiths |

Francis Woodward was a lawyer with an office opposite

the Turk's Head in Lower High Street. The Board's

meetings were held there until 1854 when they moved to

the Sessions Room adjoining the original police station

in Russell Street. The Board eventually built its own

offices in 1867 in Holyhead Road. Many of the

pavements consisted of pebbles and were very difficult

underfoot. Mr. John W. Fereday, the Town Surveyor

introduced blue bricks with a roughened diamond pattern

on the upper surface. Although they improved matters

they were often only laid across the half of the

pavement nearest the kerb. A rate of 1 shilling was

levied on the local population to pay for the Board's

activities. The Board's many achievements included:

| The building of

the Municipal Offices and Town Hall at a

cost of £4,500. |

| The building of

the public baths and free library at a cost

of £6,000. |

| The building of

the town's cemetery at a cost of £5,400. |

| A great

improvement to the town's streets at a cost

of £7,300. |

| The building of

deep sewers and the sewage works at a cost

of £5,000. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

View the Wednesbury entry in

Harrison, Harrod & Company's Directory and Gazetteer of

Staffordshire, published in 1861 |

|

| |

|

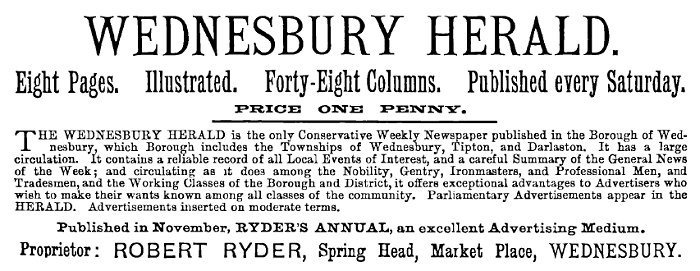

An advert from 1896.

From an old postcard.

|

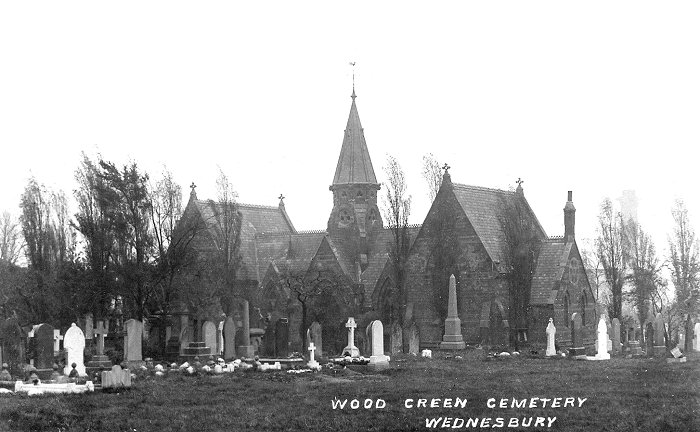

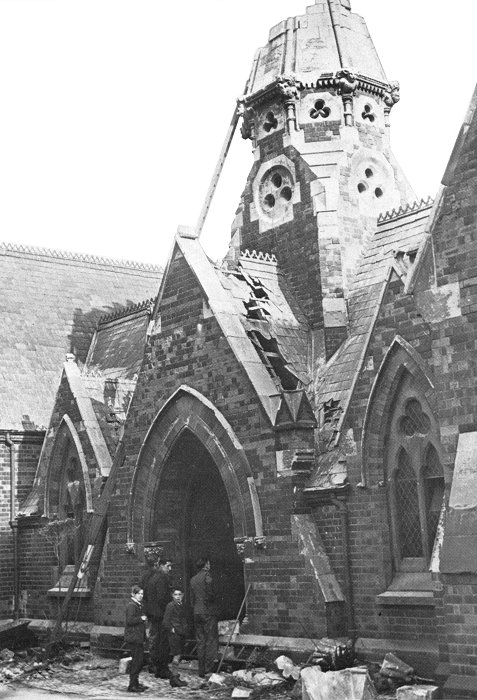

The mortuary chapel during

demolition. |

The cemetery opened in March 1868 on 12½

acres of land, and was extended in 1885.

It was built at

a cost of £10,000 and included the mortuary chapel shown

above, which was designed by Samuel Horton.

The

chapel was demolished many years ago and built in two

halves, one for Anglicans and one for

nonconformists, each holding around 80 people.

There was

also a cemetery keeper's lodge.

The cemetery was cleaned

up in June and July 2010 when many of the dilapidated

and neglected gravestones were removed. |

|

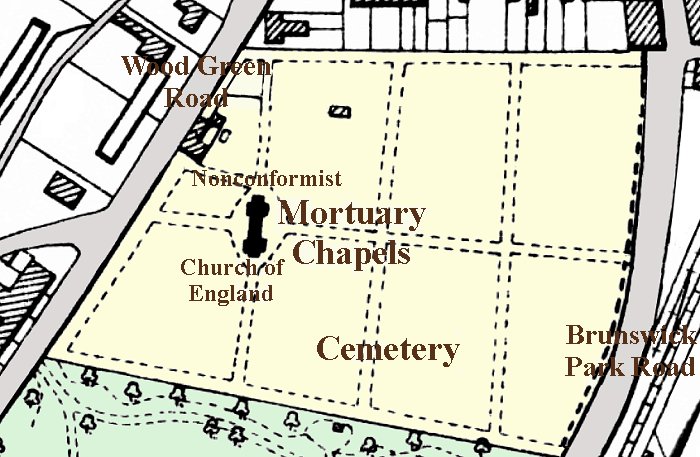

The cemetery and the mortuary

chapels. |

|

A view of the cemetery from

August 2021 with the old pumping station in the

background. |

|

Another view from August

2021. |

|

A final view from August 2021. |

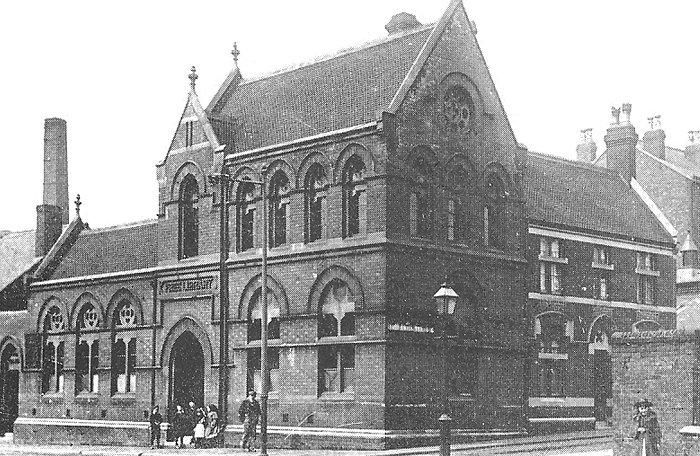

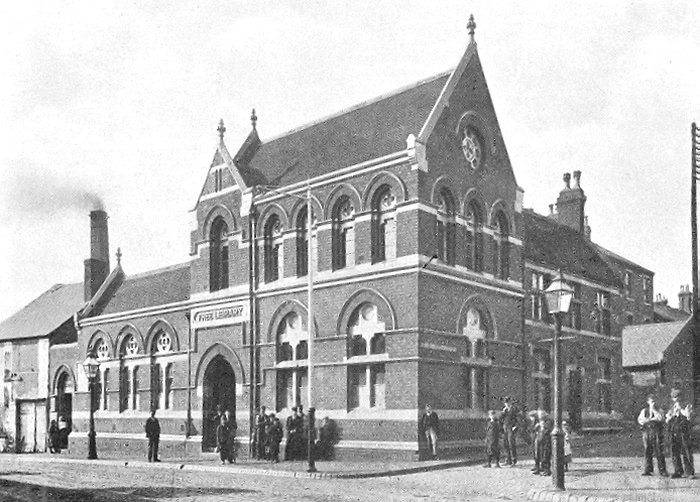

| The Free Library

and Baths that stood on the corner of Walsall Street and

Brunswick Terrace, opened in 1878 and were built at a cost of

£6,700, £1,200 of which was given by public

subscription. They were officially opened by Richard

Williams, Chairman of the local Board of Health. The

library was demolished in 1912 and replaced with new

Education Offices. The baths closed in April 1973 and

were soon demolished. The sewage works were built on land at Bescot,

acquired in 1884. The works opened in 1888. |

The old Free Library.

The old Free Library.

| The location of

Wednesbury's Free Library and Public Baths. |

|

|

Another view of the old Free Library. |

|

The new library. |

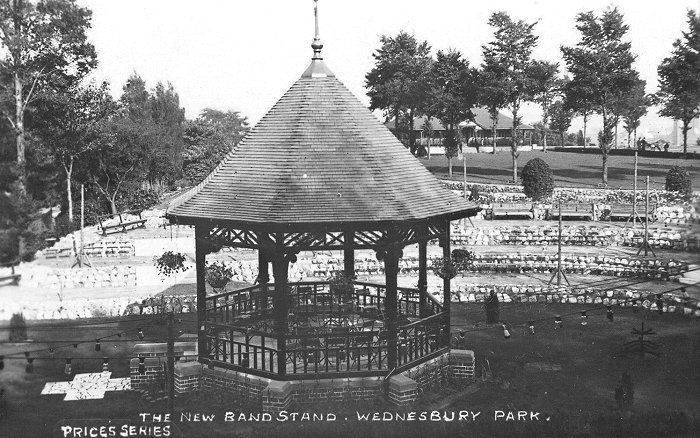

| Other new amenities included Brunswick Park which

opened in 1887 and the Art Gallery which opened in 1891

as the result of a bequest by Mary Anne Richards, the

widow of coach axle manufacturer, Edwin Richards, who

died in 1880.

Edwin had acquired a collection of

paintings by contemporary artists and they were given to

the town along with £3,500 for the building of the art

gallery, and an endowment to pay for a caretaker. |

| |

|

|

|

|

Read about the

opening

of the

new library |

|

|

Read about

Wood Green

Pumping Station |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Although the Wednesbury Local Board of Health had

made great improvements in the town, it still came in

for criticism in a report made in 1875 by Dr. Ballard, a

Government Inspector. A number of slums have now

disappeared, among them being Oatmeal Square, Bolton

Square, Beggars Row, and Pitts Square. The properties

complained of were mostly courts and alleys contained in

an area stretching from Portway Road to the High Bullen

and Trouse Lane, all densely inhabited. In many other

parts pigsties were allowed too near the dwelling

houses. There was no compulsory notification of disease;

disinfection was attempted by the cheap and primitive

process of loaning whitewash brushes, and though the

general annual death rate was not particularly high,

infantile mortality was at times excessively heavy.

Fire Fighting The

town's first fire engine was donated by the Royal

Insurance Company on the understanding that it should be

free from financial liability, for any property insured

by them, on which the engine was called to protect. The

engine was kept in the yard at the Anchor Hotel on the

Holyhead Road. Unfortunately this was too far away from

the town centre to act quickly in an emergency. In 1899

the Borough Council built the town's first fire station

at the High Bullen. The local fire brigade however,

remained a voluntary organisation for many years. |

The volunteer fire brigade in the Anchor

Hotel yard in 1897.

A view of old Wood Green looking

towards the residence of Mr. A. Elwell, J.P. which can

be seen behind the trees. St. Paul's Church is on the

right. |

An advert from 1861.

|

|

|

|

|

Return to

Transport |

|

Return to

the contents |

|

Proceed to Industries 2 |

|